We are the hollow men

But this is not how the world will end

In response to my recent essay, reader Lightwing quoted this passage:

Race is a part of identity, and it matters for understanding discrimination and history, yes, but if the goal is genuine fraternity, then our discourse must be rooted in respect, and we have to put our foot down with this shit and be clear that talking about whiteness in these ways is not respectful. It’s racist.

Lightwing then wrote:

Why can’t we all just be human? I’m so tired of grievance and endless justifications regarding why it’s okay to dehumanize this person or that group. I hate this mad era where everyone is so determined to be an avatar of righteous fury and burn the world anew.

But the fire doesn’t cleanse. It only destroys heart, the very thing that we need to repair us together again. If all we can create is despair and rage, then we will end without even the whimper Eliot promised us. What a fucking waste.

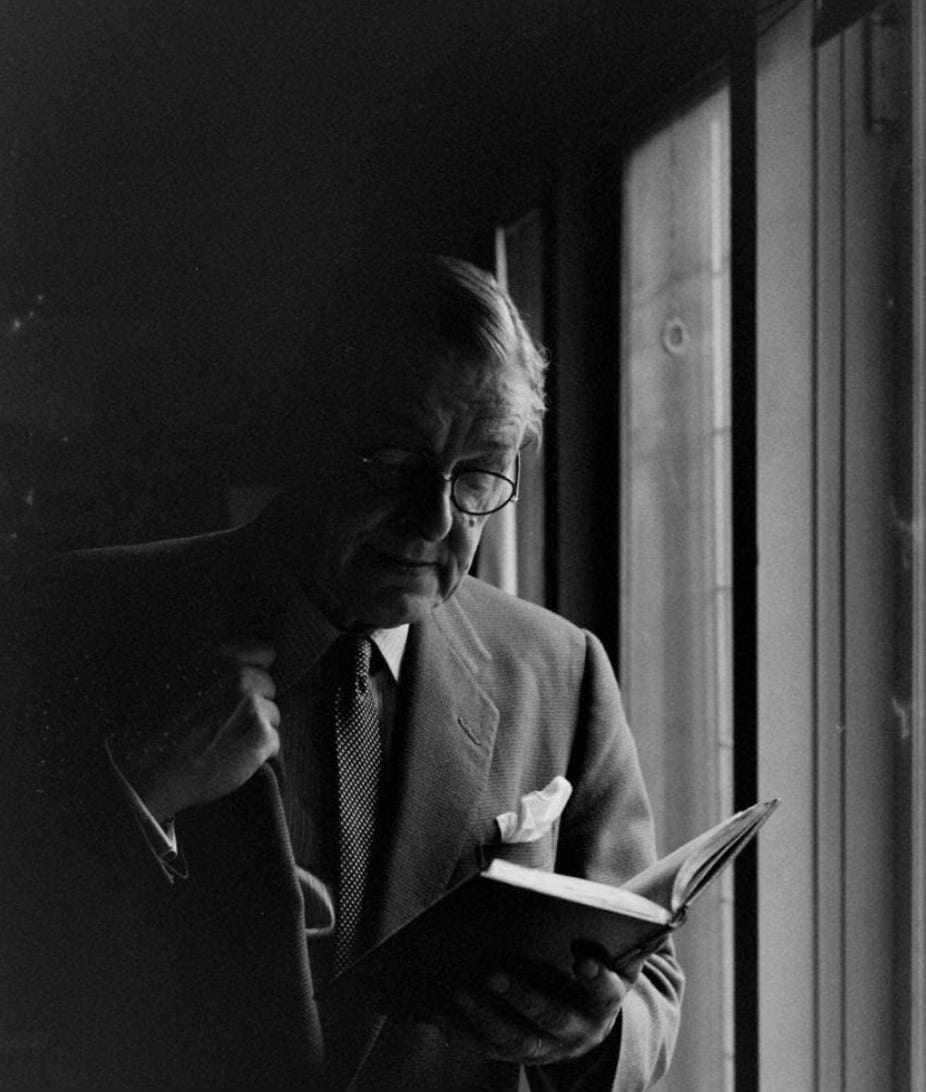

In T.S. Eliot’s desolate poem “The Hollow Men,” written in 1925, the poet describes the broken hopelessness of Europe in the wake of World War I, a world of spiritual emptiness that, in many ways, reminds me of ourselves, opening with these lines:

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw.

In his 1932 book New Bearings in English Poetry, the Cambridge-born editor F.R. Leavis argues that the poem describes humanity’s reduction to a state of ritual without faith, and speech without meaning, and again, I am struck by the way in which this echoes our present day, our crisis of meaning, how we have burned our own mouths drinking outrage fuel and now wonder why life no longer tastes as sweet.

Nietzsche called it. We are now witness to the great effort to maintain social institutions and practices without the religious glue that once held so much of this stuff together and, in the wake of that realization, a return by many to the old ways, a resurgence in Christian faith, including, of course, some of the uglier isotopic variants of Gospel belief, as well as the general relativism that exploded out of anthropology with the work of Franz Boas and Stanislaw Malinowski, who managed to convince half the world, it seems, that cultural relativity is a reasonable moral framework, and in this landscape, indeed, we are left with the husks of once-religious rituals, like marriage, stripped of their sacred skins and reduced to social performance, spiritually empty yet packed with moral signaling and metasocial preening, like so many deer head mounts on the walls of a lovely den, dead and glassy-eyed, but oh, the den is paneled with walnut, skull-scooped and straw-stuffed, but ah, so near the fireplace.

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw.

Consider what we’ve done to words like racism or genocide or woman, stripping them of meaning, keeping the structure but gutting the heart, and think of where this kind of thing leads, though I am not saying we have to move backwards in order to move forward, or that the best way to regain what we’ve lost is by the West finding Christ, rather I am saying, as others have said before me, that we clearly need something in which to ground our community, our morality, our greater sense of meaning.

Years later, in his 1965 book The Invisible Poet: T.S. Eliot, the Canadian professor Hugh Kenner, the greatest Ezra Pound critic who ever lived and doctoral student to the legendary American literary critic Cleanth Brooks, argued that the “sightless” hollow men are symbols of humanity, trapped between action and transcendence, on a bad path and unable to see a way forward, but I refuse to adopt Eliot’s perspective because I recognize one of the first thing to go when you head down this way is hope.

The great engine driving the hysterical, frenetic energy at the political extremes is not fear, but hopelessness, whether it be the MAGA hopelessness of January 6, the BLM hopelessness of the Summer of Love, or even the hopelessness of transwashed sociopaths, who are themselves victims in a way. I reject this despair. I insist on seeking fellowship with my fellow Americans, and concord with my critics. We are already on the mending path. Despite our age of fractured attention, cascading crises, and pathological fragility, the prophecy of this poem is losing its force. Now is the time to give it a good push down the hill, because if we backslide, I fear we really do face destruction, and not even what the Japanese used to call “a good death,” but rather, as the poet concludes:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

The transition we experienced was so gradual, and seemingly harmless. But it was a transition into hellish conditions that we now suffer.

That Orwellian transition took us from seeing man as an immortal soul to viewing man as a herd animal to be poked and prodded, controlled and dominated. It was a transition from caring for one another into applying the premises of animal husbandry. It was a transition into viewing our fellow man as livestock, as solely biological entities. Slaves.

The materialist vision of the utility of wetware bots overtook our sense of love one another as he has loved you. Even the purveyors of religion today, the preachers, do not rise sufficiently above the materialist ethos. They may preach the transcendent but they anchor it firmly in the views of man as an animal that saturates the culture.

T.S. Eliot and Orwell were prophets. Perhaps it time for someone to write a new chapter and verse that fully explains their prophetic vision.

I’m with you 100% here! Let’s find common ground and do the hard work of building upon it. Thanks for putting all this insight into words for us.