Bitter to the Burned Mouth

What is acceptable loss and when has Israel gone too far?

If you gaze long enough into an abyss, observed Friedrich Nietzsche, the abyss also gazes into you. This is often misunderstood as a contemplation on death or the existential void. But this is not the nihilism of full metal Nietzsche. Quite the opposite. He was referring to the human psyche, and that if you probe its depths you find a deeper version of yourself looking back, for you are the abyss and the person gazing in is but your avatar to the world. Still, there is truth in the misreading. If you contemplate the demons of the deep, before long they will slowly turn their eyes to you. Human suffering is an emotional contagion and it extracts a heavy toll.

I learned this when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Being of Belarusian-Ukrainian descent, I felt it more than most. Being a journalist, I felt a sense of duty, booked a flight the following week, and ended up writing a story for New York Magazine about a woman in Kharkiv hiding in her bombed-out apartment. She had resigned herself to death along with her mother and her 18-year-old daughter, too afraid to step outside. Instead she waited for her own abyss, watching the grey and lifeless world below. The city was now literally grey, wrapped in smoke and blanketed in powdered concrete, except only for the occasional yellow of a burning vehicle or sidewalk splashed in red.

In the end, therapy sessions gave her the strength she needed to run, literally saving her life and the lives of her family. Hers was one of dozens of stories I collected, some so gruesome I could not repeat them to my wife when I phoned home at night. Meanwhile, my wife had become strangely distant. I didn’t know it then, but she was pregnant with our daughter and didn’t want to break the news over the phone. She had become consumed with the fear that her husband would die in a war zone never knowing he was a dad. Meanwhile, all the stories of horror I was consuming in interviews began to wear on me and I broke down weeping in an interview as one woman told me what had become of her husband. When she saw me cry, it made her cry, and the interview stopped, and we cried together. I later wrote on Twitter how unprofessional this made me feel because my emotions had not only ruined an interview but triggered the subject. Thankfully, former CNN anchor Monita Rajpal gave me some needed advice.

“It may seem insane to take care of your mental and physical health while countless people around you are suffering,” she said. “However, if you look at it as necessary to continue to be of service to them … you’re helping them by telling their stories, by listening to their pain. To keep helping them, you have to find a way to decompress.”

These words were an anchor in the roaring tempest. I returned to them later when interviewing genocidal rape victims from the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. I wrote about the Tigray genocide for The Nation and about the subsequent refugee crisis for Foreign Policy. But again, the stories I collected in interviews were so hideous they began to influence my mood even when I was away from the work, doing other things. In the end, I took therapy to help unravel some of the horrors that had planted themselves in my mind, and ended up becoming a student of cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy.

In the wake of October 7, I have returned once again to Monita’s wisdom as I find myself consuming endless hours of unthinkable atrocity and growing bitter from the exposure and from the sickening response we have seen across the West.

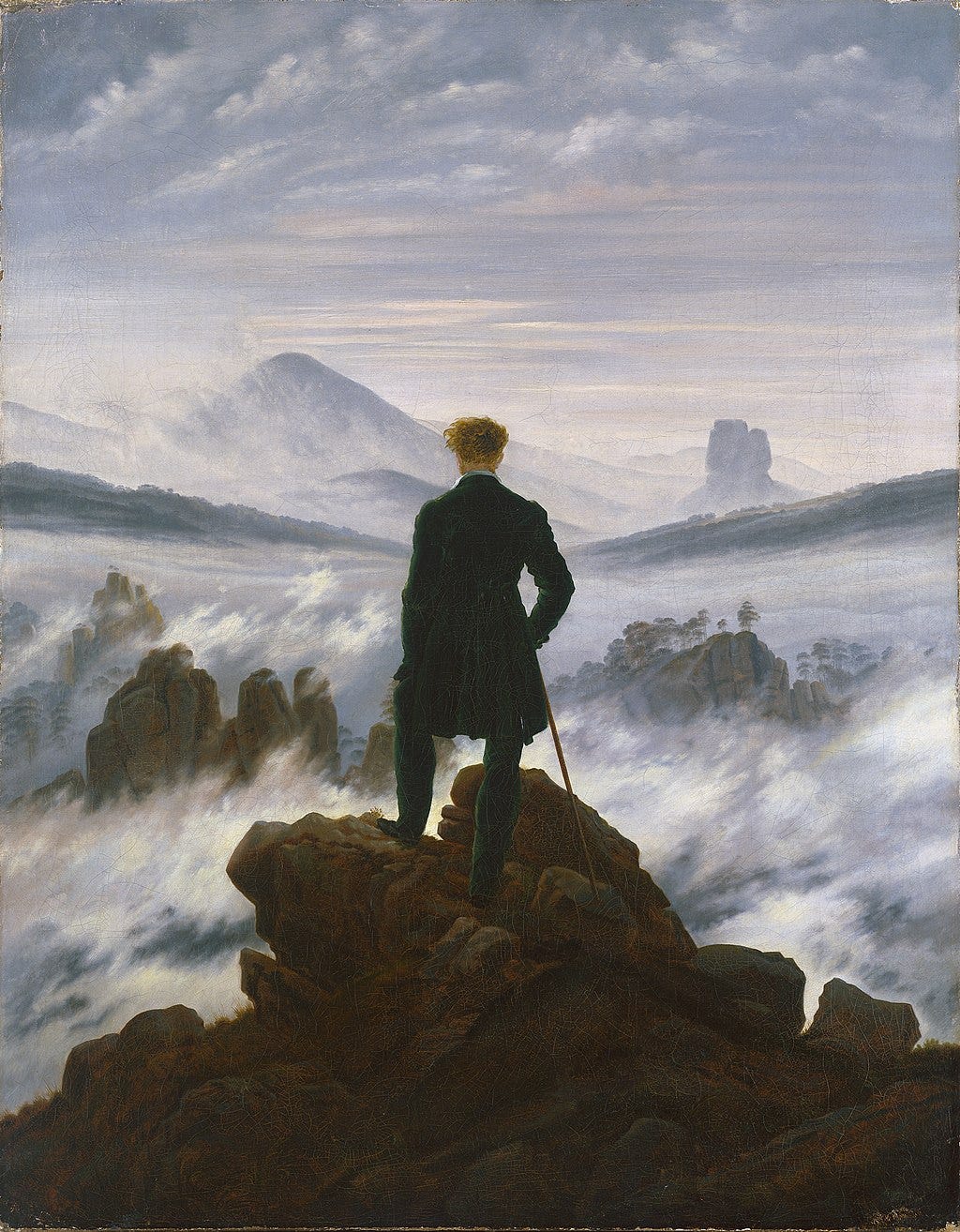

Nietzsche was not a nihilist. He was a diagnostician of nihilism. He observed the growing sense of meaninglessness around him, but rather than embrace it, he looked down upon it like the green-cloaked man in that famous masterpiece of Romantic painting, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, which is itself a celebration of triumph over chaos. Like that painting, and like my friend Monita, Nietzsche offered not just hope, but a method for climbing out of the abyss.

A very strange genocide

Israel is carrying out a genocide in Gaza, we are told in logic that sounds like a 56k modem dial-up. How do they imagine, you have to wonder, that one of the most formidable military powers in human history is trying and yet somehow failing to eradicate an ethnic group within its own borders, a group already crowded together in a small region that is only 25 miles long and 7 miles wide? If genocide is the goal, it would take Israel minutes if not seconds to accomplish. Yet Israel has been at war for nearly three months and has only killed about 22,000 people according to Hamas figures, which pencils out to roughly 1% of all Gazans. If Israel is attempting genocide, it is arguably the most powerful military to ever do so and is failing worse than any ever has.

In 1964, Israel banned the first independent Arab party for the Knesset, Al-Ard. And as of 2017, there were over 65 laws against Palestinian citizens in Israel. But these problems only exist because Palestinians citizens of Israel exist. If Israel were attempting genocide, an early stage would be to strip people of their citizenship. Israel is not doing that. The next stage is dehumanization with genocidal incitement to violence. In Israel, hate speech is illegal. If Israel is carrying out a genocide of Palestinians, why do Palestinian citizens of Israel exist? Why do they have the right to vote in Israeli elections, as they have since the first elections in 1949? Certainly what you would never do if you are a government trying to eradicate an ethnic group would be to allow that ethnic group to become part of your government. But in the 2022 legislative elections, five Knesset seats went to the Hadash-Ta’al list, which is made up of the Arab-Jewish communist Hadash Party, led by Ayman Odeh, and the Arab nationalist Ta’al Party, led by Ahmad Tibi, who identifies as Palestinian by nation and an Israeli by law. This means there is a member of the legislature of the nation of Israel who does not necessarily consider himself a member of that nation.

In addition to the list, five Knesset seats went to the Israeli Palestinian Ra’am Party, led by Mansour Abbas, which is part of the southern branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel (the branch that decided to take part in Israel elections and win seats, not the northern branch, which boycotts democratic elections and has alleged ties to Hamas). Can anyone point to another genocide in history where the perpetrating government allowed the target population to maintain political parties? Was there a Zionist Party within the Nazi government, and if so, how many Reichstag seats did it hold, or is this just an obviously stupid question? There are roughly 14.3 million Palestinians worldwide. In this war, Israel has only killed 0.15% of them. Why isn’t Israel carpet bombing the West Bank? There are 5.3 million Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, but there are over 2 million in Israel itself, so why not at least arrest these people? There are also more than 3 million in Jordan, so why not invade that country? What kind of genocide is this?

What people really mean when they say genocide is simply that they think Israel is killing too many people. They think Israel is guilty of disproportionate killing. But proportionality is another commonly misunderstood concept because the principle of proportionality does not mean that the response should be proportionate to the initial attack. It does not mean that if Hamas kills 1,400 people in Israel that a proportionate response is to therefore kill 1,400 people in Gaza. Hamas raped Jewish girls, so Israel get to rape Muslim girls? By that logic, Hamas could continue to kill thousands of Israelis at a time, and Israel would hypothetically kill the same number in each response, until 2 million Israelis will have been murdered whose lives could have been saved, and every living person in Gaza would be gone. You would have a Jewish genocide, and in response, the utter eradication of Gazans, and this would be proportionate and therefore everyone would nod approvingly and go home or turn to the next page in their daily paper. Is that supposed to be the idea?

This insane conceptualization of the principle of proportionality would have Israel respond to genocide with genocide, rather than by attempting to prevent any future genocide. Thankfully, that is not what the principle of proportionality means or has ever meant. The International Committee of the Red Cross defines the principle of proportionality as prohibiting military attacks that are “expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life … which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.”

Proportionality is not an attack that is proportional to the initial attack, but one that is proportional to the military advantage being sought. In this case, the eradication of Hamas. A disproportionate response is not one that exceeds 1,400 civilians, but one that exceeds whatever is required to eliminate Hamas. Because Hamas has embedded themselves in civilian infrastructure in order to maximize civilian death, and because Hamas uses human shields and does not wear military uniforms to distinguish themselves from ordinary Gazans, naturally the number of civilians that will necessarily be killed in order to eradicate Hamas will be quite high, far higher than it was in previous conflicts where the enemy did not embed itself, where the enemy fought on battlefields, where the enemy wore uniforms, and so forth. The 2020 Operational Law Handbook, published by the National Security Law Department, says of proportionality:

The use of force in self-defense should be sufficient to respond decisively to hostile acts or demonstrations of hostile intent. Such use of force may exceed the means and intensity of the hostile act or hostile intent, but the nature, duration and scope of force used should not exceed what is required. The concept of proportionality in self-defense should not be confused with attempts to minimize collateral damage during offensive operations.

Israel’s response violates the principle of proportionality if it goes beyond what is required to eliminate Hamas, not if it ends up killing a lot of civilians in the process of eliminating Hamas. The same concept is echoed in the U.S. military’s collateral damage estimation methodology (CDM), which was outlined in an October 2012 report for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The report noted that the CDM centers on five questions that must be answered before engaging any target:

Can I positively identify the target?

Are there civilians or noncombatants within range?

Can I lower those deaths with another weapon and finish the mission?

If not, how many will be injured or killed?

Is that number proportionate to the expected military advantage?

The full quote from Nietzsche’s passage about the abyss is, “He who fights with monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” We have these rules because we are not them. We conduct war, in fact we do it far better then they can, thank God, and we do not let the death of civilians stop us from eliminating those who kill civilians for sport. But this still doesn’t answer the question, what number is excessive in relation to the military advantage of eradicating Hamas?

In the Era of Nietzsche

Nietzsche did not accept the erosion of moral values that came with the reassessment of God’s existence. Gott its tot, he famously said. God is dead. But people get this one wrong a lot too. He wasn’t declaring his atheism, but simply observing that as belief in the Judeo-Christian God fades, so will the authority of Judeo-Christian values, leading to a kind of moral nihilism. We see this now with the rise of relativistic postmodernism and woke progressivism. But in the face of this fact, Nietzsche felt the only thing to do was to assert value. Perhaps you cannot base your moral claims on the authority of divine will, he said, but that doesn’t mean you cannot arrive at the same conclusions. This assertion is why some think of him as the godfather of existentialism, because in the void of existence, the only meaning we have is that which we choose to create.

This argument was a product of the time in which he lived. One century before, in the 1781 work Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant had argued that the faculty of reason can be divided into the things that we perceive, or phenomena, and the reality that lies beyond the limits of our perception, meaning things as they truly are, or noumena.

The argument was revolutionary. If you were to name just four inflection points in the history of Western philosophy, they would be the Socratic turn from thinking about the natural world to thinking about the human world, the Aristotelian synthesis, from the human world to methodology itself and the birth of logic, the Enlightenment, taking us from logic to objective reasoning and applied science, and the existential turn from the objective world to subjective experience. Kant was the grand philosopher of the Enlightenment, above Voltaire or Locke, and the Critique was the basis of that stature. Kant took the famous allegory of the cave but, unlike the prisoners who are released at the end of Plato’s story in the Republic, he said we can never be released because our own senses are the chains that bind us. Plato’s point was that people live in what Friedrich Engels would later call “false consciousness,” that we are unaware of reality and the solution is education. But Kant said we cannot even take the first step. We can never get closer to the truth, but can only guess based on flickering shadows on a cave wall. The visible spectrum for humans goes from violet to red, or wavelengths of light between 380 and 750 nanometers. We can’t see ultraviolet light (below 380 nm) but bees can and it helps them find flowers. We can’t see infrared light (above 750 nm) but snakes such as boas, rattlesnakes, and copperheads can and it helps them find prey.

In his 1807 book Phenomenology of Spirit, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel said reality is not permanently beyond our reach, and we can slowly get closer to it through a dialectic process of offering ideas, pushback, and resolution. But in the two decades before Hegel arrived, Kant had convinced many Europeans they could not trust their own senses. Add to this the social alienation and disillusionment of the Industrial Revolution, the erosion of religious belief and fraying of the order and sense of meaning it had granted. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species about his voyage on the HMS Beagle, studying finches and barnacles on the Galápagos Islands, and his theory of evolution through natural selection, further upending our religious understanding of the world and our place in it. Then came the unification of Germany under Otto von Bismarck in 1871 and the rise of nationalism, which Nietzsche hated, and Bismarck’s defensive system of alliances that backfired in Germany’s face when the Bosnian Serb terrorist Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, and that defensive system of alliances pulled everyone into World War I.

This is the context in which Nietzsche wrote the line about the abyss in his 1886 work Beyond Good and Evil. The Enlightenment of the 18th century gave us a more rational understanding of the world, but the skepticism of the late 19th century turned away from truth and progress. Thanks to Kant, the Industrial Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, and German unification, objective truth had faded. In his book, Nietzsche tried to grapple with this loss and with the increasing uncertainty of the modern world. He rejected the simplistic binary of Judeo-Christian moral thinking and what he called slave morality, which prizes kindness and humility, as opposed to master morality, which prizes power and assertiveness. He wasn’t opposed to kindness, but to self-destructive kindness, arguing instead for the will to power, or as Jordan Peterson would put it, moving up the dominance hierarchy.

This means manifesting one’s essential nature and overcoming the weakness of dogmatic thought while rejecting the Christian instruction to be meek, which was never the true instruction—the original word in Matthew 5:5, “blessed are the meek,” is praus πραεῖς, which does not mean weakness but power under control, or as Peterson says, “those who have swords and know how to use them, but keep them sheathed, shall inherit the world.” Nietzsche believed transcending conventional morality to achieve this made you a better person. An overman or Übermensch.

Master Morality in War

But how do we think about this in the context of real-world events? How do we work through the moral calculus when it comes to war? War is the father of us all, Heraclitus wrote. I often think of a similar but darker passage from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, in which the diabolical figure of the Judge listens to someone talk about the Bible.

The good book does indeed count war an evil, said Irving. Yet there’s many a bloody tale of war inside it.

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

So then, to the question at hand—when does Israel go too far? Specifically, how many Gazan civilians can Israel kill and retain the moral high ground? Is it even possible to affix a range to such a thing, or is it the case, as the political commentator Douglas Murray has implied, that there is no line at all? I do not know the answer, but I know how to think my way through the question.

Even in the best of circumstances, where the enemy is easily identified and the terrain is as open and clear as possible, as in desert or naval warfare, you have mistakes. Consider that so far in this war, the IDF has lost about 105 troops as of December 12, and 20 of them were killed by friendly fire. That’s 19%. Are IDF troops deliberately killing each other, or is the nature of this urban war inherently confusing?

Dense urban warfare is already chaos, but far worse when the enemy does not wear identifying uniforms or deliberately embeds itself within civilian infrastructure and among crowds. Hamas also uses ambush tactics and deception, such as the sound of crying children played over loudspeakers to draw IDF troops toward strategic locations. When IDF forces recently killed three hostages who were shirtless and waving white flags, officials later explained they thought this too was an act of deception and so mistook the hostages for Hamas. This kind of confusion is by design.

I reject the Dresden defense. This is the argument that the Allies killed too many people in the bombing of Dresden, and therefore they were actually the bad guys, not the Nazis. The joint British and American air forces dropped 3,900 tons of ordnance in the bombing of Dresden on February 13-15, 1945, killed up to 25,000 people.

Hamas has about 20,000 members. Israel intends to kill them all. So far, Hamas claims about 20,000 civilians have been killed as a result of Israel’s response to the October 7 massacre. Let’s take that at face value for now. With this kill ratio, we’re looking at 80,000 civilians dead to wipe out Hamas. How do we process a figure of that scale?

Well, in World War II, Germany had a population of about 70 million people and lost about 1-3 million civilians. Japan had a population of about 72 million and lost almost 1 million civilians. That’s a range of about 1% to 4% of their populations, and if we can agree that the civilian death toll was worth it in order to defeat the Nazis and the Japanese Empire, that equates to 20,000 to 80,000 people in Gaza.

Another way to look at it is that we killed 43,000 civilians in the bombing of Hamburg, 50,000 in the bombing of Berlin, and 100,000 in the bombing of Tokyo. Moreover, these episodes of conventional bombing did not, on their own, wipe out the enemy nor end the war. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed up to 226,000 people, arguably accomplished that task, but not on its own.

Yet when we talk about 80,000 Gazans, we’re talking about entirely wiping out Hamas, and 80,000 is on the lower end of the range noted above. So the current kill ratio of 1:4 is in the middle of what we have already deemed the acceptable range based on previous conflicts. Even a 1:6 ratio would be within the range and that would mean 120,000 civilians in Gaza. Anything higher is not therefore automatically wrong, but it would be beyond the limits of what most historians and Western societies today have understood as acceptable in previous conflicts. In other words, if Israel continues at the same rate then when Hamas is gone and we look back on this war, the civilian casualty figures will compare favorably to other major conflicts. And if we aren’t holding Israel to the same standard, then as Natan Sharansky has famously argued, w’ere probably doing antisemitism.

How high does the range possibly go? Well, I suppose the most cold-blooded answer would be to say that Hamas wants to kill all Israelis, and Israel has the right to prevent that at any cost, so long as the cost is less than what it would be if Hamas succeeded. In other words, so long as you minimize death, so long as what you do means fewer dead than if you don’t do what you’re doing. There are 9.5 million people in Israel, so that would mean anything below 9.5 million is better than the alternative, and there are only about 2 million people in Gaza.

That is horrifying to consider. Not all Gazans support Hamas. Then again, not all Germans were Nazis. In fact, only about 9 million Germans were party members and the Nazis were elected to power with about 44% public support. But in Gaza, about 80% of the population supports Hamas. They not only support Hamas, but specifically acts of terrorism and murder carried out by Hamas. According to one poll, 72% of Gazans support the atrocities carried out on October 7, which Hamas has vowed to repeat until there are no Jews left in Israel.

The Nazi death camps did not have 72% support of the German public. For one thing, the existence of the death camps were not widely known until after the war when the Allies discovered them.

So let’s look at the grisly math. As we know, about half the population in the Strip is under 18 so that’s 1 million people right there. You can reasonably argue that a 16-year-old Nazi is a fair target when he’s holding a gun, but let’s put aside all minors for now. That leaves 80% of the adult population who support Hamas and October 7, the equivalent of Germans who would have supported Hitler and the gas chambers.

That means 720,000 people who are not Hamas militants, of course, but neither are they morally innocent if they want Hamas to stay in power and carry out a literal Jewish genocide. When we reflect on the defeat of Nazi Germany, I have never in all my years of historical analysis and research come across a single tear shed for any German-born Nazi who felt that the death camps were great and who wanted to see the Holocaust completed. Nor does anyone really give a shit if you tell them how much the Germans suffered in the wake of World War I, and they suffered worse than the Gazans of today before October 7. But we don’t care. We don’t think of such people as innocent. We think of them, in point of fact, as Nazis. In fact these days, you get called a Nazi for far less than wanting to see the Holocaust fulfilled, or in the case of Gaza, wanting to see a new one begun.

Besides, I guarantee you this, the IDF is not going to kill 720,000 people. Or even half that. They may be visiting upon Gaza what Jim Morrison called a Roman wilderness of pain, but they are well behind the bright red line of transgressing any conceivable standard we have ever set in prior wars. We live in an age of moral erosion and relativistic depravity, much like the one in which Nietzsche found himself, with disinformation actively sowing confusion, and in this abyss I agree with Nietzsche that we simply must assert morality in the void. We must be the good we wish to see. And I think he is right that it must be a Judeo-Christian morality, not to the exclusion of others, but to the inclusion of its framing of moral rights and the value of human life, but not a dogmatic way. We must assert a morality of kindness, but a kindness that cannot be mistaken for weakness. We are in war, and in war, a master morality is required. As I recently wrote:

In war, what you do when facing an enemy that wants to visit unspeakable evil upon the innocents of your land, is crush them into oblivion, not give them a nation.

What you do is defeat them so utterly that there is nothing left of their desire to rape and kill your people, as we did with Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, the Confederate States of America, and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

This does not mean that Israel’s conduct is perfect or that it could not prosecute this war better than it is now doing, with reduced loss of life on the other side, of course that’s true.

This does not mean that we harden our hearts against the suffering of peace-loving Gazans or their beloved children, but neither do we hesitate to fight for the sake of our own children.

So while I certainly do not think that Israel intends to eliminate everyone in Gaza, and in fact I find claims of Gazan “genocide” to often be antisemitic, nevertheless we must not stubbornly pushback without allowing for any dialectic as it were. We must force ourselves to listen to the voices of the Palestinian people, watch the videos, and look at the images. As I have in Ukraine, with Tigrayans, North Koreans, and Uyghurs, we must gaze into the abyss if for no other reason than not to lose sight of ourselves. And what we do, even if we think of it as a necessary evil, is a scar we must not hide. To invert Nietzsche’s formula, we must gaze into the abyss so that it does not gaze into us. As a friend recently advised, every time you want to comment on the war in Gaza, before you do, fix the image of a suffering Gazan child in your mind, and let that be your emotional gut-check on your own opinion. On that note, I leave you with the words of the poet Denis Levertov writing about the Vietnam War:

Did the people of Viet Nam use lanterns of stone? Did they hold ceremonies to reverence the opening of buds? Were they inclined to quiet laughter? [...] Perhaps they gathered once to delight in blossom, but after their children were killed there were no more buds. Sir, laughter is bitter to the burned mouth.

I study and teach history, and specifically Jewish history. I have read accounts of slaughters, from Crusade to Chmielnicki to Hevron. A good Enlightenment Jew, I believe in progress, both technological and human, yet I know that a mere dozen years before my birth, Jews were still be slaughtered in a way that reflected technological perfection, of a type. My shocking revelation on October 7 is how ideologically unprepared I was for the brutality, joyous brutality of the slaughter. And the joyous brutality of those of the enlightened West who supported the slaughter.

To put it in your paradigm: we are confronted with people who simply have no abyss. There is nothing inside of them that is reflected by a mirror of humanity. I’m not saying they are not human. What I am saying is that I am shocked at myself for thinking, for believing with no supporting evidence, that humans like this could not actually exist in our day. Can one say another human being is soulless without losing one’s own soul? I think the answer to that is yes - and I believe that is a foundational idea of the Jewish people.

The issue then becomes how one does battle against the soulless. The American government seems to believe that they should be rewarded with a state. Kick the problem down the hill for a few years until the next slaughter and reprisal, some more dead Jews at the hands of the soulless ones, and some of them and their children will die too.

The strategy of Hamas is called Mukamawa. It means long-term low scale asymmetric warfare aimed at the moral attrition of one’s enemy. It is the “M” of the acronym of the organization called Hamas. Every time an episode like this erupts, we deal with it, but the cost over time will eventually undermine our country. I don’t know if that could happen, nor do I know if our country could survive the kind of steps that would need to be taken to distance this threat from our borders, even that led to a better life for both sides.

But we have to look and we have to see. We have to see, as you said, the cost of taking up arms to fight against this expression of inhumanity, a fight we neither asked for nor desire, but one from which we are adjured to press. We have to see that suffering Palestinian child and know she is suffering because her leaders see her more precious as dead rather than alive. And we can’t let that image stop us, weaken us, from fighting this war relentlessly, without quarter, because that is the only response I can reasonably take when I see the images of the butchered, maimed, slaughtered, and burnt of October 7. When I think of the hostages still held by the soulless.

It has nothing to do with the numbers. I don’t know why you left the path of talking about morality in our day and turned to numbers. We need clear moral sight much more than we need a scorecard. Proportionality says nothing about the rights and wrongs of a conflict, and we have to be clear-minded and (yes) responsible enough to be able to talk about rights and wrongs. Clear-minded and (yes) responsible enough to confront the relativism of the post-modernists and the false god of the victim narrative and the purportedly oppressed. If we can’t do that or are afraid to do that, we are lost.

And also keep in one's mind the images of beheaded Israeli babies, bodies burnt beyond recognition, women gang-raped, murdered and mutilated - and realize that Israel is fighting for them as well as for - not against - that suffering child in Gaza. It is easy to be seduced by power, by ideology, by the evil of one's enemies. Not all Israeli or Israeli soldiers are immune to such seduction, but over time we do see that the Israeli army as an institution adopts policies to restrain the beast within, and the soldiers who lose themselves inside the abyss are rare. One policy aimed at restraining the beast is to make sure that Israeli soldiers get home to the civilizing influence of their families and communities, sometimes just for a day or a shabbat. While I always thought that the wrenching shift from war to warmth to war again might result in numerous AWOL soldiers, in fact it motivates while also renewing belief in things that are good and warm. I am wary of the trust in power that our army seems to embrace, I think the army and government has shown that we remain faithful to the values that make Israel a Jewish state, while our enemies have shown that our acquisition and use of power is unfortunate, but justified.