The bädao of Palestine

The Boulder attack, a Palestinian burns his wife alive, plus new survey data

On Sunday, an Egyptian Uber driver named Mohamed Soliman used a makeshift flamethrower and Molotov cocktails to set over a dozen people on fire as they peacefully marched through Boulder, Colorado, calling for the release of the Israeli hostages in Gaza. As he did so, Soliman shouted, “Free Palestine!”

This phrase is the new “Allahu akbar,” the takbir of terrorism, and the last two words you want to hear someone cry in a public crowd.

The next day, a 72-year-old Jewish man was posting flyers about Israeli hostages on New York’s Upper East Side when someone slugged him in the head and shouted, “free Palestine!” Two weeks ago, someone shot and killed a young couple in D.C. outside the Capital Jewish Museum, yelling “free Palestine!” Almost one year ago, a man stabbed a Jewish man near the headquarters of the Chabad movement in Brooklyn, yelling “free Palestine!” Almost two years ago, a man broke into a Jewish family’s home in Los Angeles, yelling “kill Jews!” and “free Palestine!”

Palestinians and their allies have taken this call for liberation, this chant of protest, and made of it a genocidal war cry alongside “Hutu power!”

Perhaps one day Khaled Beydoun can write a book explaining how “free Palestine” has been unfairly associated with terrorism, as he did with the phrase Allahu akbar in his 2023 book The New Crusades: Islamophobia and the Global War on Muslims. Until then, we will simply have to settle for the paltry validation of hard data repeatedly confirmed through empirical evidence.

The moral fog is so thick in this neck of the woods that apparently we can’t even figure out who to care about in the wake of a terrorist attack. Take the recent one in Boulder, where the media seems more concerned with how this will impact the terrorist’s family than the actual victims.

Among the burn victims in Boulder this week is an 88-year-old woman named Barbara Steinmetz, who came to America as a Holocaust refugee. Born in Hungary in 1936, Barbara grew up on the banks of the Adriatic Sea on the island of Lussinpiccolo, where her parents ran a hotel. In 1938, Mussolini stripped Jews of citizenship as part of Italy’s alignment with the Nazis, so Barbara’s father took the family and left the home they’d made among the olive trees.

They returned to Hungary, where they pleaded with relatives to follow them. But, as Steinmetz recalls, “They were scared. They simply couldn’t envision what was to come. Or that their friends and customers would turn on them.”

In 1940, the Steinmetz family fled Hungary for France, but the Nazis arrived within months. That winter, they moved to Barcelona, then Madrid, then Lisbon. But Portugal was overrun by Jewish refugees, and the family was now almost penniless and desperate to find a way out. Her father applied to the governments of Canada, New Zealand, Great Britain, Iceland, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, Ghana, Kenya, Cuba, the United States, and South Africa. But at the Evian Conference of 1938, where 32 countries convened to address the Jewish refugee crisis caused by the Holocaust, only one nation agreed to accept further Jewish refugees: the Dominican Republic.

And so the family headed to the Dominican Republic.

According to Steinmetz, the Dominican dictator Trujillo accepted Jewish refugees partly because his daughter had attended a prestigious boarding school in France, where she befriended the daughter of a German Jewish industrialist. But in truth, Trujillo accepted Jews for two, far less charming reasons. One, to improve his reputation after having ordered the Parsley Massacre, in which tens of thousands of Haitians were slaughtered. And two, to whiten the nation’s population with light-skinned European immigrants.

Not only that, but he didn’t even keep his word. In the end, despite offering to take up to 100,000 Jews, Trujillo only took in about 700. But miraculously, Steinmetz’s father secured his family within that number, and booked passage on the Portuguese cargo liner the SS Nyassa. Barbara still remembers docking at Ellis Island in New York Bay, and seeing the Manhattan skyline out her window.

Once they arrived in the Dominican Republic, they settled in the town on Sosúa, where they were plagued by mosquitos carrying malaria as well as giant tarantulas. Barbara and her older sister attended a Catholic boarding school where only the mother superior knew they were Jewish. Eventually, the family moved to the United States, where he father took up work in a New Hampshire hotel. Once day, after they had settled into their new life, Barbara told her father she unhappy in New York.

“You think I care that you’re unhappy?” he replied. “You’ve got a roof under your head. You’ve eaten. And we’re not on the run. You think I care that you’re unhappy?”

But eventually, Barbara did find happiness living in America, and in the 2000s, she moved to Boulder. After being set on fire this past week, her response was simple. “We’re Americans,” she said. “We are better than this.”

But why aren’t we getting reports like this from the news?

Well, part of it is simply the result of the competitive news cycle’s need to dig up any uncovered aspect of the story. Fishing for clicks will pull up some ugly fish. And the framing makes easy use of our natural inclination to feel sympathy for the suspect’s daughter. She’s innocent in this, after all. But the reporting doesn’t provoke emotion simply to engage the reader. It directs it. Because, of course, we’re not going to get a USA Today story about the troubles now facing the victims’ children.

Part of this is also the moral perversion that seeks to frame power as evil in simplistic Kendian fashion, for just as Kendi believes that inequality of outcomes between racial groups is evidence of racism, there is the related belief that inequality of power is evidence of oppression. Yes, if one racial group has all the political, economic, and cultural power within a country, it could be that this country is profoundly racist. Or it could be that this country is Finland. Or Japan.

In a way, this belief is the logical conclusion of Christian moral reasoning, or to be precise, of a common misunderstanding of the third Beatitude and what Nietzsche called slave morality. As I wrote in my essay “Bitter to the Burned Mouth,” the worship of the weak was not the original message of the third Beatitude:

The original word in Matthew 5:5, “blessed are the meek,” is praus πραεῖς, which does not mean weakness but power under control, or as Peterson says, “those who have swords and know how to use them, but keep them sheathed, shall inherit the world.” Nietzsche believed transcending conventional morality to achieve this made you a better person. An overman or Übermensch.

The disciplined shall inherit the earth, which makes considerably more sense. But mainstream Christianity interpreted “meek” as submissive, resulting in the common logic on the political left that the oppressed are, by virtue of their oppression, morally righteous. Of course, it’s quite possible to be both oppressed and immoral, indeed oppression often drives one to evil. During Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, slaves armed with hatchets and knives went from house to house, freeing fellow slaves and killing whites, including 10 infants and toddlers, leaving “whole families, father, mother, daughters, sons, sucking babes, and school children, butchered, thrown into heaps, and left to be devoured by hogs and dogs, or to putrify on the spot.”

Now take this concept of the virtuously oppressed, remove the Christian admonition against violence — which had begun to fade even within the Church as soon as it began to integrate the structures of Roman power with the Edict of Milan in 313 — replace it with the Leninist logic that oppression must be violently opposed, and you end up with a situation where violence can be justified so long as the perpetrator can be framed as a victim of oppression. This is how we end up with a Vox Explainer on how blacks murdering Asians is actually white supremacy. Or an essay by a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder arguing that the disturbing rise in the number of blacks attacking Asians is actually white supremacy. Or Columbia students trying to convince the world that Hamas are the good guys, actually.

In addition to Christians and communists, we can blame culturalists, by which I mean anthropologists. As I have written before, Nietzsche was right when he predicted that if the West abandoned the moral frame of Christianity, nihilism would follow, as it has done. In The Gay Science, he famously wrote, “God is dead,” but few have actually read this passage or understand what it means. He is not saying that God is literally dead. Nor is he simply saying that belief in God has died. Here’s the passage:

Haven’t you heard of that madman who in the bright morning lit a lantern and ran around the marketplace crying incessantly, “I’m looking for God! l’m looking for God!” Since many of those who did not believe in God were standing around together just then, he caused great laughter. Has he been lost, then? asked one. Did he lose his way like a child? asked another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone to sea? Emigrated? Thus they shouted and laughed, one interrupting the other. The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. “Where is God?” he cried. “I’ll tell you! We have killed him — you and I! We are all his murderers. But how did we do this? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sidewards, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Aren’t we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Isn’t night and more night coming again and again? Don’t lanterns have to be lit in the morning? Do we still hear nothing of the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we still smell nothing of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How can we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers!

This is not merely about disbelief in God, but about the collapse of the entire Western value system built on Christianity. Once “we unchained this earth from its sun,” we are doomed to be “continually falling … as though through an infinite nothing.” But in our infinite wisdom, that’s exactly what we did. So now the West is in the middle of a crisis of meaning. Having removed that in which our moral system was grounded, and replaced it with nothing, indeed nothing is what filled the gap, the nihilism of nothingness, of no moral absolutes, and it is in this vacuum that the cultural relativism spread like a virus. As I wrote in my essay “The Case for Colonizing Gaza”:

We are only now waking up from the misguided efforts of Franz Boaz, Michel Foucault, and the rest of the moral relativists who convinced so many of us to drink deep of the lie that all religions are created equal and all cultures are worth saving. Yet we know better than to pretend the culture of contemporary New Zealand is comparable to the culture of Nazi Germany. The militarist culture of Imperial Japan and the jihadist culture of Islamist Iran are abject failures whose legacies include such achievements as the Nanjing Massacre and October 7.

My studies of the Palestinian people and their cause often reminds me of my early days as an undergraduate student, when I was conducting ethnographic research in the tropical highlands of Peru and reading about an intellectually out-of-fashion fellow named Napoleon Chagnon, whose work transformed the entire field of anthropology — right before critics accused him of racism.

His 1968 book Yanomamö: The Fierce People has a mixed and polarizing legacy. A study of the Yanomami people of the Amazon rainforest, the book had a seismic impact on the field of anthropology. For one thing, its application of evolutionary psychology to explain Yanomami behavior, especially warfare and violence, was revolutionary. He argued that violence conferred reproductive advantages because men who killed had more wives and therefore more children. Chagnon also pioneered longitudinal fieldwork with quantitative data, staying with the Yanomami for decades and gathering not just genealogies, but demographic data and reproductive histories. This kind of long-term, data-heavy ethnographic research heavily influenced later methods in biological anthropology and demography. His book also became one of the best-selling ethnographies ever, was widely used in college classrooms, and brought anthropology to a mass audience.

But the book was polarizing because, as you can tell from its title, it depicts the Yanomami as “primitive” and living in “a state of chronic warfare.” This, in turn, triggered a global debate about research ethics because although Chagnon tried to offer a raw, honest look at the Yanomami, as opposed to the “noble savage” ideal, he was criticized for describing the Yanomami as violent. Indeed, critics accused him of biological determinism, even racism, for imposing a Hobbesian framework of “savage” vs. “civilized.” In 2000, journalist Patrick Tierney published Darkness in El Dorado, accusing Chagnon and geneticist James Neel of unethical behavior — and of harming the Yanomami. Although many of Tierney’s claims in the book were later discredited, the controversy triggered intense scrutiny over ethics in anthropological fieldwork. This led to major reforms in institutional review board policies and anthropology’s internal ethics standards.

But here’s the funny thing — the Yanomami are violent. Incredibly violent. In his 1985 account Tales of the Yanomami, anthropologist Jacques Lizot, who lived for more than 20 years among the Yanomami, tried his best to dispel this stereotype:

I would like my book to help revise the exaggerated representation that has been given of Yanomami violence. The Yanomami are warriors; they can be brutal and cruel, but they can also be delicate, sensitive, and loving. Violence is only sporadic; it never dominates social life for any length of time, and long peaceful moments can separate two explosions.

So although they can be loving, these are brutal and cruel people whose society goes through sporadic explosions of violence? Not very convincing, Jacques. In the 1930s, a Brazilian woman named Helena Valero was kidnapped by Yanomami warriors and reported this description of a tribal raid:

They killed so many. I was weeping for fear and for pity but there was nothing I could do. They snatched the children from their mothers to kill them, while the others held the mothers tightly by the arms and wrists as they stood up in a line. All the women wept ... The men began to kill the children; little ones, bigger ones, they killed many of them.

And yet the entire field of anthropology had a global ethics debate because Chagnon described the incredibly violent Yanomami as, well, violent. We don’t have to guess what Chagnon thought of his woke critics in the discipline because he put his opinion right in the title of his memoir, Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes — the Yanomamö and the Anthropologists. One lesson to learn here is that the sensitivities of academia around such issues tend to reach escape velocity from reality fairly easily.

A more important lesson is that Chagnon was right. Some cultures are more violent than others. Some are more immoral than others. Often it’s easy to see. Last month, I came across the following Jerusalem Post story on my way to work, “Palestinian to be charged with murdering Arab Israeli woman as she birthed their son,” which began:

A West Bank Palestinian man is to be charged with the murder of an Israeli woman, whom he allegedly killed as she was giving birth to their baby, the Israel Police said Monday. …

After her partner killed her, he burned her body, which was found with a newborn boy still attached to her via the umbilical cord, police said. The 35-year-old suspect, a resident of the West Bank village of A-Ram just outside Jerusalem, also later sold her car.

Naturally, we cannot condemn an entire people on the basis of one murderer, yet we can identify patterns of behavior within societies. We can understand that the 35-year-old sociopath in the story above did not materialize from the ether. He grew up in a culture where this kind of horror is not only normalized, but lionized:

Hello? Hi, Dad! I'm talking to you from Mefalsim. Open my WhatsApp now and you'll see all those killed! Look how many I killed with my own hands! Your son killed Jews! Allahu akbar! May God protect you! Dad, I'm talking to you from a Jewish woman's phone! I killed her and I killed her husband! I killed 10 with my own hands! Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar! Open WhatsApp and see how many I killed, Dad! Open the phone, Dad! I'm calling you on WhatsApp! Go! Dad, I killed 10, 10 with my own hands! Put Mom on! Oh my son, God bless you! I swear, 10 with my own hands, Mom! I killed 10 with my own hands!

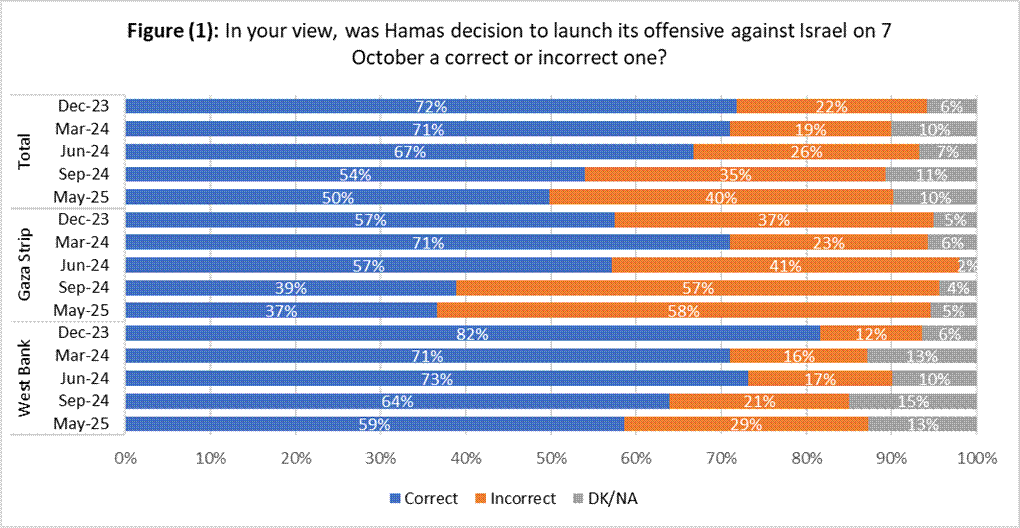

Still, qualitative data only gets us so far. What I keep repeating, and what is so important to understand, is that the vast majority of Palestinians approve of such conduct. Here’s a survey from last month showing that 59% of West Bank Palestinians believe what Hamas did on October 7 was “correct”:

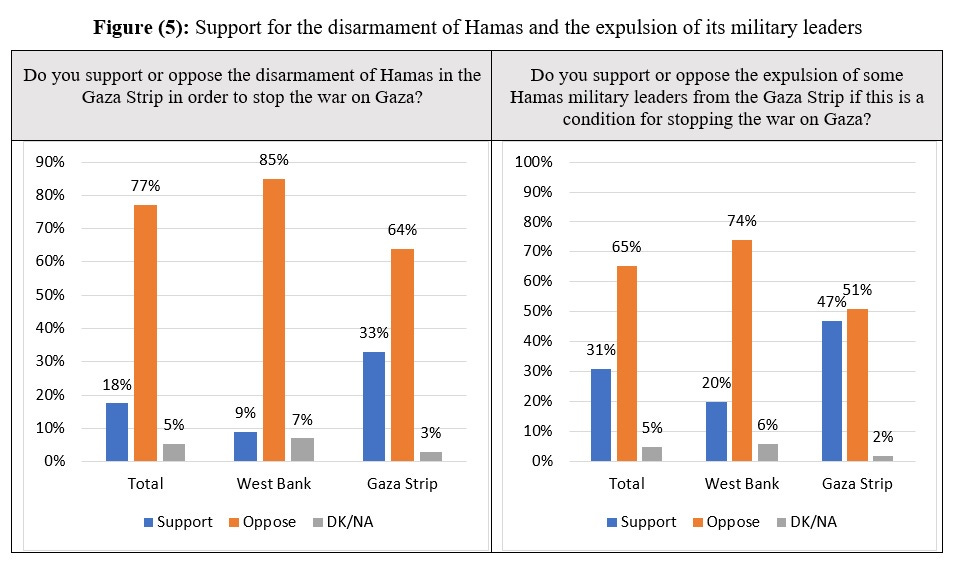

Far more disturbing is the fact that 85% of West Bank Palestinians and 64% of Gazans oppose the disarmament of Hamas while 74% in the West Bank and 51% in Gaza oppose even the expulsion of some Hamas military leaders in order to stop the war. Pause for a moment to consider the full weight of that statistic.

The overwhelming majority of Palestinians would rather continue the war than have even some Hamas leaders kicked out.

Recently, the Wall Street Journal released an exclusive report titled “Hamas Wanted to Torpedo Israel-Saudi Deal With Oct. 7 Attacks, Documents Reveal,” which begins:

Top leaders of Palestinian Islamist group Hamas launched their Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel aiming to torpedo peace negotiations between Israel and Saudi Arabia, according to minutes of a high-level meeting in Gaza that Israel’s military said it discovered in a tunnel beneath the enclave.

This means people like Mariam Barghouti, who wrote “On October 7, Gaza broke out of prison,” are simply liars or idiots. October 7 was not a prison break, and Palestinians themselves know this. Some cultures are simply more violent than others. Some types of violence are better than others. Some cultures are better than others. Often for me, the analysis comes down to a simple principle: do people in this culture justify harming the innocent? Do they celebrate or honor it?

The Yanomami have many different words for killing, including bädao, which means killing without good reason. In Yanomami culture, bädao is the worst kind of killing. In Palestinian culture, honor is a kind of bädao.

David, thank you for bringing so many interesting bits together. Sadly, today's garbage is still piling up and the Devil is feasting.

The common thread that runs through every cause embraced by the radical left - violence.