Summer of my discontent

A review of Thomas Chatterton Williams’ Summer of Our Discontent

“History is the consequence not only of people’s actions, but also of their forgetfulness.”

– Salman Rushdie

“To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought.”

– James Baldwin

“But the fact is that writing is the only way in which I am able to cope with the memories which overwhelm me so frequently and so unexpectedly. If they remained locked away, they would become heavier and heavier as time went on, so that in the end I would succumb under their mounting weight. Memories lie slumbering within us for months and years, quietly proliferating, until they are woken by some trifle and in some strange way blind us to life.”

– W.G. Sebald

Sometimes it’s hard to believe that the greatest historical moment of my lifetime has likely already come and gone. When I think back to the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic five years ago, it feels like an alien landscape—a piece of history. It makes me wonder if there were similar jarring moments for the people who lived through the Spanish flu of 1918-1920. No doubt there were. But much of what has been said about that experience has, like a lot of things, been lost to the historical record. We certainly have an idea of how people lived through those times, and how they reacted afterward, but the sheer amount of first-hand accounts we have from the years of 2020-2021 almost certainly casts a deep, dark shadow over the first-hand accounts we have of every epidemic in human history. And yet, those nine months of emergency feel more remote and odd even than other massive historical events, like 9/11.

I have said multiple times in multiple places—on my podcast, on my Substack, on other people’s shows, in my class meetings at grad school, and in private conversations—that there seems to be a tendency for human beings to develop very strong amnesia when it comes to pandemics and epidemics. I have speculated that a lot of it has to do with the fact that pandemics—and illness in general—is something most people simply do not want to dwell upon, thanks largely to the fact that when it comes to illness, there are no winners. There is no struggle that can be overcome while the virus is leveling everything and everyone. Everything is defined by loss or near-loss. Often, those losses are not limited to loss of lives, but loss of what was once normal, usually through state policy and social choice—whether one is talking about the loss of a place to work or the loss of seeing your friends’ and loved ones’ faces behind masks. An existence defined by such losses—such a net negative existence, in other words—leads to what I am starting to believe defines the reason why no one particularly likes to dwell on: a persistent and seemingly incurable sense of rage.

That rage so many experienced during the pandemic years was beautifully and devastatingly articulated by the excellent Chicago-based writer Jeffrey Blehar over at National Review, in a piece he wrote earlier in 2025 in which he described the total and utter failure that was (and has always seemed to be) Chicago politics, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was wrapped up in what can only be described as state-sanctioned abuse of his son with special needs, something that I will likely (hopefully) never experience first hand. The rage Blehar felt and expresses in his piece is truly palpable, and I cannot recommend it enough for some insight into this emotional state I am describing. However, I think when we look back at the COVID years—as I am prone to do, with greater curiosity thanks to the distance created by time—I remember a lot of rage, and not just at state failures, lockdowns, inconsistent messaging, and other right-coded things. Those identifying with the left felt plenty of rage, but instead of pouring it into these right-coded causes—they were those who believed in science, after all—they displaced it into the supposedly more rational cause célèbre of social justice so persistently that it took on a religious revivalist character, as we all remember (and as I have discussed).

I was—and as it turns out, perhaps unsurprisingly still am—no exception to feeling rage during that awful first year of COVID. And over five years on, I find myself reflecting on how that rage manifested. Clearly, much of it was turned into work—two podcasts dealing with historical pandemics and their effects, totaling around ten hours of content, as well as several essays—in which I tried to look at what was enraging my fellow Americans from a 30,000 foot vantage point, supposedly in order to understand this rage at scale. However, while I groped around for that meaning that I could assign to my angry countrymen, I did not stop to consider that this was turning into my own expression of rage at the futility of the world in which I lived. “How could we not see how we are repeating the biggest follies in our history?” was my frequent exclamation. As it turns out, just because you have removed yourself to 30,000 feet over the world, does not mean that you are somehow removed from it.

And yet, as it turned out, it was through that rage that I ultimately learned how to free myself from it and not even realize it until many years later.

As many of you reading can no doubt already tell, this will get more personal than things usually do on History Impossible. But clearly, nothing else has fully “worked” when it comes to publicly making sense of my own experiences five years after COVID-19 and its attendant chaos. Forget what made everyone in the United States so angry: what made me so angry? That is the question with which I started to struggle. It was not the virus—that is an inhuman, inevitable part of the human experience. It was not the government or institutional failures themselves—those could be and were reversed. In truth, it was, ultimately, the people themselves, and how they revealed themselves to be, well, human. And part of being human is indeed being deeply, deeply flawed, especially in the face of existential horror. And, as someone who does sometimes allow himself to have a shred of optimism about what people are capable of at the worst of times, that was a profound letdown. Was my standard too high? Perhaps. But it did not cushion the disappointment—and ultimately, rage—when I watched our institutions fumble vital messaging; when I watched institutional representatives flaunt their disregard to safety or, especially, not live up to their own standards; or when I watched double standards be applied on a truly societal scale, in order to justify mass incivility and opportunistic nihilism.

It is therefore not surprising that I have remained plagued by the remnants—the memories—of this rage I experienced in and about 2020, even five years on. I have mined everything—or close to everything—I possibly can when it comes to trying to exorcise that rage demon through my work apart from taking an honest, personal approach. And for me, there is little else more personal than reading meaningful work from writers I could only aspire to emulate. Thus, it made perfect sense that my reaction to reading what I can confidently say will likely be my favorite book of 2025 (and arguably many years for some time to come) was what it was; that is, Thomas Chatterton Williams’ Summer of Our Discontent: The Age of Certainty and the Demise of Discourse.

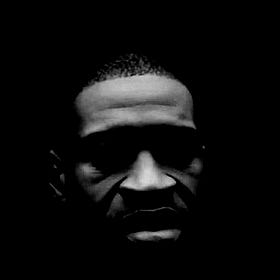

To put it plainly, Williams’ book was a powerful catharsis for me. Never before had someone collated the relevant anecdotes and the relevant data, and described it all in the appropriate prose. Williams did the work of a journalist as well as a prose stylist, in the tradition of writers like George Orwell, William F. Buckley, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, and Christopher Hitchens, and really brought us—brought me—back to that turbulent summer and the feelings of rage that defined (and somewhat still define) it for me. Williams’ previous work—particularly his 2019 book Self-Portrait of Black and White—similarly blends genres (more like memoir and philosophy, in the case of Self-Portrait) deconstructing identity in such a way that it made him, at least in my opinion, the perfect documentarian of the pandemonium that defined the year 2020. He does not start during that summer or with the shocking death of George Floyd, but instead takes us back to the heady days of 2008, in which so much of America—particularly young, liberal America—was swept up in the excitement of having elected our first black president. It was indeed a heady moment; I should know, because I was there, at 22 years young, as excited as anyone else.

And indeed, that excitement faded for me about as quickly as it did for everyone else, something that Williams charts quite ably. The difference, though, was that I saw Obama as the kind of change that works, not the kind of change that people my age believed we needed. As I saw it, even though he ran on the promise of being the antithesis to that warmonger-in-chief we all so loved to hate George W. Bush, he was also the guy that said in 2007 that he would send forces into Pakistan if it meant taking down Osama bin Laden. This was a liberal candidate who, despite having his bonafides, was also a liberal candidate with balls, and he had no interest in kowtowing to what was obviously a fangless “anti-war” movement, which had taken me all of one hour to become annoyed with when I attended my first and only anti-Iraq War rally on March 20th, 2003 (admittedly, my 17-year-old brain was more excited about going to see Billy Corgan’s post-Smashing Pumpkins supergroup project Zwan’s show at Minneapolis’ famous First Avenue club that same night). Was this a limited way to appreciate the world politically? Absolutely, but again, I was 22 years old when I first voted for Obama and very few people that age are more sophisticated than a James Cameron script.

Regardless, I was excited by Obama, and I have no shame in admitting that part of it was indeed because he was to be our first black president and because of what, in my mind, that fact meant: that we were approaching a truly post-racial future in a country so overly defined by racial difference during most of its existence. Williams explores this, to use that word again, heady feeling that pervaded back then—this excitement for our post-racial future—and it drew me back to my own feeling of confusion that so many people—scratch that, everyone—I knew expressing overt reticence and even discomfort to admit the very thing that I just admitted at the beginning of this paragraph. There was, in liberal Minneapolis at least, a bizarre unwillingness to even acknowledge Obama’s obvious blackness (to say nothing of its political and historic appeal), and while I think it was more because they wanted to avoid giving the right-wing commentariat of the time like Sean Hannity or Bill O’Reilly any “ammunition” (for what, I was never sure), it was never particularly coherent and at least gave me a very clear window into how white progressives tend to treat the subject of race (that is: never bluntly and always through a rhetorical veil of weird justifications). Now to be fair, it was also likely due to Obama’s own overt avoidance of the subject, something that, as Williams notes, likely helped him win the election so handily in 2008. But generally speaking, the people avoiding race talk the most in the late 2000s were the good, white, urbane liberals. Strange as it might seem now, it was the style at the time.

So while I thought there was nothing wrong with celebrating the thing that obviously granted Obama a Nobel Peace Prize (that Christopher Hitchens rightfully called a “virtual award” at the time), clearly everyone, including the new president himself, did not agree and I was largely alone on this supposed courtesy. The president’s race was not on the table in any context (unless it was to make snide comments about why anyone in the Fox News or talk radio orbit criticized him or his policies). But nothing lasts forever. When Trayvon Martin was killed by that “white Hispanic” George Zimmerman in February of 2012, Obama’s tone changed. As Williams explains in his book, it was a bit of a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation with our former president, and one with which Williams and I both sympathize, both then and now. As a black American man himself, how could Obama not bring up the elephant in the room? Well, one, he could have avoided paying attention to social and online media noise or the people on his team that did not avoid that noise. He could have simply condemned the attack for what it was: overindulgent vigilantism against a teenager. He could have remembered his pledge to be a president to all Americans (which yes, did and does not preclude him from speaking his mind and heart in the way that he did, but let’s stop being naïve). But he did not do any of these things, and instead made his fateful “could have been my son” comment. While there was and honestly is nothing wrong with that on a basic human level, as Williams pointedly explains, this comment revealed the moment that there was a difference between the Americans who wanted a black president (a clear majority) and the Americans who realized they had a black president (not so much, as we came to see). Taking advantage of this vibe, Black Lives Matter was born.

How Black Elites Destroyed BLM

David Volodzko speaks with Freddie deBoer about the origins of cancel culture, the failure of the Black Lives Matter movement, the impact of education on politics, and more.

The chapters that follow that moment in Summer of Our Discontent chronicle the trajectory of the BLM movement, as well as the broader social justice discourse that dominated the 2010s, which began to crescendo with unmistakable intensity following Donald Trump’s first election. It is safe to say that we all know what happened next, and how truly unhinged parts of the American left started to become during that time. By the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, nothing could really cause anyone to be surprised at the fervor that dominated political discourse in the United States. Annoyed? Disturbed? Even horrified? Sure, especially during the height of the #metoo moral panic. In a real way, the collective delusion that defined summer 2020’s chaos was something completely unsurprising to anyone who had been paying attention to the wider culture. But it was never about the delusion as much as the behavior that attended that delusion that was so horrifying. Screaming into the digital void about white supremacy is one thing; looting and burning down buildings, assaulting and even killing people, and justifying it with high-minded pretentious rhetoric is something completely different. Thomas Chatterton Williams was, among a relatively small number of liberals at the time, one who understood this as it was happening, and his writing in this book makes it clear.

The completely empty, useless, nihilistic reality of utopian ideals is revealed in stories like this; completely avoidable tragedy . . . that only existed because of what was, by any and all metrics, truly criminal levels of stupidity and arrogance.

The moment that Summer of Our Discontent’s resonance truly struck me centered on an incident that occurred in “George Floyd Square”—the place of his death, rendered for years into a squalid pseudo-autonomous zone of cobbled together religious significance—that very few people knew or seem to know about (or, especially in the case of progressive Minneapolitans, have chosen to forget). The incident captures all of the chaotic hypocrisy, incoherence, and infuriating functional callousness and cruelty of modern social justice advocacy (that, as I have made clear, probably would be less of a problem if the religious aspect of those concerns was appropriately embraced). Williams sets the scene as follows:

For the truest of true believers, such as the mostly white anti-police activists who attempted to prevent police and emergency personnel from accessing George Floyd Square—a chaotic pilgrimage site that retains a pseudo-religious ambience to this day—to deliver aid to a woman who had been shot there in December 2020, the very meaning of basic words, such as “harm” and “safety,” could be reengineered so that their esoteric understandings eclipsed all common sense. In this way, since black and other non-white people were by definition subject to racist violence with regard to the institution of policing, even allowing a fellow protester to bleed to death on the street in the absence of law enforcement personnel was a vision of comparable security.

This alarming incident had scarcely been reported. When I interviewed Jeanelle Austin, the charismatic young executive director of the George Floyd Global Memorial, at a Minneapolis coffee shop in 2021, she explained to me that the area in those days was essentially lawless and impenetrable, regulated by motivated neighbors and activist members of the local community on their own terms but also in constant negotiation with other outside agitators, many of whom were not even black and seemed to, as Austin put it, “hate cops more than they loved black people.” The only way a journalist could even physically access the square without being forcibly evicted in those days “was that they had to be vouched for by a community member,” Austin explained. […] Within this information silo, “a black woman was shot,” Austin conceded.

I had indeed not heard this “scarcely-reported” story. However, it felt strangely familiar because the first time I returned to the Twin Cities since the pandemic, in the summer of 2022, I had a nearly first hand encounter with the violence inherent to George Floyd Square. I was returning home with my partner from a family friend’s house. We made our way through the Square slowly in our car, and noticed that the number of people who were gathered there had increased in the couple of hours we had been gone. This was to be expected, we had been told, as well as it being not a good idea to linger there for too long after dark. Sure enough, we learned the next day that someone had indeed been shot in that square and, as it turned out, it had occurred only eight minutes after we had driven through the decrepit intersection. It hardly registered with many people I knew in Minneapolis because, frankly, it had become the norm, as made clear by the December 2020 shooting described by Williams, whose outcome could no doubt have been avoided had it not been for the ideological frenzy that defined much of Minneapolis (and the country) that year. In his book, Williams allows Jeanelle Austin tell the story in her own words that I feel are worth repeating here:

I got a message on my phone. It was late at night. And there was a shooting that happened in George Floyd Square, the police are here, protesters are not letting the police in, there’s no black people here. And so, I was like, “Okay, I’m coming.” And so, I first stopped and I talked to the medic on-site and I said, “Brief me, what’s happening?” And she briefed me on everything and said the patient refused treatment, but they were bleeding severely and [that] “I’m afraid that she might bleed out.” And [she added], “If those protesters are not letting the police in to investigate, they can get charged with aiding and abetting.” So I’m like, “Okay, what’s happening?” And the protesters didn’t know any of that. They’re just anti-police in this moment.

So then, I show up, and then a couple other black neighbors show up and we started talking to say, “Okay, here’s the situation.” And I briefed them on what the medic told me. And I’m like, “We have to be able to figure out how are we going to get justice for that young black woman who got shot.” That’s how I framed it. We have to be able to center her life first. But then we were also dealing with a community that had real police trouble, because the police militarized themselves and marched in our communities. But based off of the information that we had, trying to say, “Okay, what do we do?” And one of the neighbors, who was actually a black neighbor, she said, “Well, let’s pray for her.” And so I said, “Okay,” because I’m a person of faith. And I said, “Okay, that’s fine.” So we had to pray now.

So, you have community members, who are also protesters. I say protesters, but these are not outside folks, literally people who live here, this is why people can get there so quickly, because they were residents. So, you have people who are there, you have police officers, and then you have everybody, we’re pausing to pray. We get done praying, and then I look up and I said, “Okay, and now what? Now what do you all want to do?” And nobody had a solution. [Emphasis added].

Eventually, led by Austin and other community members, police officers—each escorted by a community “buddy officers”—came in and conducted an investigation that ultimately led nowhere. There was no evidence of police abusing their authority in this case, nor militarization, and everything occurred within the bounds of the law and the standards being applied to the community. While the woman who had been shot survived, it is not a stretch to say that this moment of “community solidarity” was likely small comfort to her as she was bleeding into the snow. It was also small comfort to the seven people who would be killed by gunfire in and around the ghoulish memorial site, including a pregnant woman named Leneesha Columbus and her prematurely-delivered baby, during the course of the three years of consistent gatherings.

Reading this account, and those others, and thus remembering my own pseudo-near miss so close to my childhood home, stung more than I thought would be possible. The completely empty, useless, nihilistic reality of utopian ideals is revealed in stories like this; completely avoidable tragedy—though truly, at this point in the chronology of 2020, I suppose it had become pure farce, to paraphrase Marx—that only existed because of what was, by any and all metrics, truly criminal levels of stupidity and arrogance. Reading it, and thinking about this, brought back all of the impotent helplessness—really, the horror—that I felt at watching my hometown of Minneapolis appear to go truly insane in a way only explained by literary allusions, like Lord of the Flies or even A Tale of Two Cities. Truly, it felt like the destruction unleashed upon Gotham City in the underrated The Dark Knight Rises, except there was no singular populist demagogue like Tom Hardy’s Bane egging on the destruction; rather, it felt like an undulating, tentacled mass of ideological zombies on the streets and social media feeds were doing the job without such a calculating supervillain even being necessary.

Many people—myself included—have said things like “Minneapolis burned” during that hellish summer, and that, as it turned out was a mistake, because it left room for literalist retorts against such things (even though many buildings were indeed burned to the ground to the tune of half a billion dollars). I remember hearing a lot of people—friends, family—still living in the Twin Cities say the same thing: it’s not like what the national (or “conspiratorial right wing”) media is depicting. I never had much to say to that except, “I’m glad you’re not personally seeing it.” I always quietly thought (or sometimes loudly said, depending on who I was talking to), you also have no idea what is happening at scale or, more importantly, what this looks like from 30,000 feet or what longer-term effects this will have. To the people that did see it and somehow still think it was a good thing, well, I don’t speak to those people anymore (and not necessarily by my own choice).

I have vague memories of the salad days of “Murderapolis” from when I was a child growing up in the Twin Cities in the early 1990s. Obviously, I was kept away from such violence as best as possible; after all, that was “just the North Side” as was often said (in a not-so-subtly-coded racist implication, given the demographics of the North Side). But there was no escaping the reality of it, even when I did not see it with my own eyes. There was a home raid two doors down from my house as I was growing up; I still do not know why. There were shootings within a few miles of my home, the taped-off aftermaths of which I occasionally saw. I had classmates and friends, mostly Asian as it happened, whose families had been ripped apart by violence, including gang-related drive-by shootings, given the influence of Lao and Hmong gangs in Minnesota, especially around that time. I even had a long-time friend murdered in 2008 in what was possibly a gang-initiation killing, resulting in a swath of collective trauma among almost everyone I knew or with whom I was close.

But these events were always in my periphery. Obviously, the place I lived was not, proverbially speaking or literally, “on fire.” However, the ambience of violence was ever-present, and thus normalized, and even—especially for a young man in his late teens and early twenties seeking to prove his toughness and resilience—something about which to be proud. This was just city life, after all; I didn’t want to be like those sheltered suburban kids from White Bear Lake or Edina, after all. Or, god forbid, those rural hicks outside of St. Cloud or New Ulm, right? This may have seemed acceptable then, but given where things went in 2020—especially to a man in his mid-30s, now over 3,000 miles away and largely a completely different person than who he was at 22—the zoomed out view revealed some uncomfortable truths about how we make normal what is decidedly not optimal.

That is why pointing out the physical destruction met upon a large swath of South Minneapolis—a place about which I have so many fond and troubled memories that I would never choose to forget—is unhelpful, distracting, and ultimately does not get to the core of just what was so upsetting about the response to an objectively tragic event within a larger, tragic context—that is, the death of George Floyd, in the midst of our hopeless condition created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The physical destruction—which included at least one death—that occurred as a result of the social unrest justified by Floyd’s killing was bad enough. But what made that reaction so horrifying was the obvious destruction of sanity that motivated it, and the glee experienced by those engaging in and cheering on the madness, even from afar on social media, making it all the more ghoulish, inhuman.

This was only made worse by the policy proposals that followed in tandem and in the wake of the chaos that engulfed the collective psyche of Minneapolis. Scratch that: it defined the collective psyche of Minneapolis. The defiant denials of reality from the Minneapolis City Council (as well as wider news media, which of course included the infamous “fiery but mostly peaceful protests” chyron from CNN) combined with the performative trauma-dumping on display from the mayor at George Floyd’s funeral (which became embarrassingly viral to the point of infecting the national Democratic establishment), and the melodramatically-worded Facebook and Instagram posts from countless people I knew (or thought I knew) made it clear that my hometown—and by extension a wide swath of the country—had indeed succumbed to a pandemic of a different kind. It was not COVID, and it was not systemic racism: it was a pandemic of contagious madness.

The Logic of the George Floyd Debate

Last month, Coleman Hughes wrote an essay on George Floyd for The Free Press in which he argued that Derek Chauvin is not a murderer, but a scapegoat. After reading it, I posted the following comment on Notes and X:

As the incomparable Dan Carlin once said, “Madness on an individual level is one thing. Madness that is contagious is another.” Contagious madness leads to the acceptance of mad proposals, which are, in turn, accepted by those who caught the madness bug, despite any objections by those who have not. In Minneapolis, it just so happened that oftentimes (not always, but often) those who did not catch the madness bug were those who the insane among us believed they were helping most: that is, “Black and Brown bodies,” to use the parlance of the time (or, more appropriately, black people who actually lived in the communities affected by the madness that was, largely it seemed, held by white Minneapolitans). This might have been embarrassing, or even funny, fodder for a classic Dave Chappelle skit, but it had a toll. It had a deep, dark, depressing toll, for which no one ever actually took responsibility—neither the people who pushed the madness via policy or those who supported the madness tacitly via social media. This was something Thomas Chatterton Williams captured vividly in his book’s most powerful chapter, when he wrote the following:

The dream was prematurely interrupted. By November of that same year, The Washington Post reported that homicides in Minneapolis had skyrocketed 50 percent, with nearly seventy-five people killed across the city. More than five hundred people had been shot, “the highest number in more than a decade and twice as many as in 2019. And there have been more than 4,600 violent crimes—including hundreds of carjackings and robberies—a five-year high.” The majority of that violence occurred after the killing of Floyd and the subsequent push to “end policing as we know it”—a rhetorical gambit that led, according to the city’s Latino chief of police, Medaria Arradondo, to more than a hundred officers vacating the force, a figure more than twice the annual rate.

This explosion of violence included the woman shot in December 2020 that had to wait for treatment in order to soothe the egos of activists gathered at George Floyd Square in the middle of a winter night. While one cannot discount the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic—I have no doubt in my mind that none of this madness would have happened without it and the heavy-handed attempts to put a lid on it, to say nothing of the poor leadership President Trump exhibited in those early months—the madness that gripped the rest of the United States and even, as Thomas indicates in his book, much of the world, was and will likely always be the defining feature of the year 2020 as it becomes more of a piece of history rather than a piece of commentary. As much as I appreciated Williams’ book beginning with the optimism that defined the immediate post-2008 years—ironically, given the economic reality into which we were heading, but understandably, given the very real hype behind our soon-to-be-first-black-president—I believe he captured the madness better than any other writer thus far. It is immediate and visceral, and it is unbreakably connected to a “before time,” and “after time.”

The “before time,” is indeed that two to three year period following Barack Obama’s first election to the office of the presidency. The “after time,” begins with the chaos of January 6th and moves through the now-obvious gradual rollback of radical social justice’s cultural ascendency. Sandwiched between these two periods of time is that collective madness, and when positioned this way, we are first met with a striking portrait of a culture that was profoundly let down by the supposed failure of our new post-racial future this new president supposedly represented. That letdown, among other stressors, leads to a persistent attempt recapture the intense sense of purpose that was lost with that realization of a failed utopia. This, then, culminates in a mass self-immolation of credibility that is not even realized until it is far too late, and the man allegedly responsible for the riots of January 6th, 2021, is reelected as president.

While Williams’ book does not end with Trump’s reelection, it does end with the anti-Israel protests that followed Hamas’ pogrom of October 7th, 2023. This might seem ancillary to the narrative, but it in fact does reveal that the era of collective madness was over. After all, had those protests against the supposed apartheid state committing an ongoing genocide carried with them the same mass-scale destructive madness as the ones that erupted after George Floyd’s killing, it is unlikely that the tide of public opinion would be turning against Israel in 2025. In truth, as disturbing as many of the post-10/7 protests could be in certain respects, it is clear—and this is Williams’ point—that the political schtick to which they were committed was about as worn out as a political schtick could be. It was not even about Israel or Hamas or anything like that; it was the collective hangover created by the bender that was that madness that culminated in the summer of 2020. In that sense, the “before time” and “after time” that bookend the central chapters are vital for understanding that collective madness; the collective madness could not exist without these eras of optimism and impotent nihilism.

Or is it really all that impotent?

Perhaps in 2024, when Williams was writing this book, it might have seemed so. Now in our final quarter of 2025, the impotence of post-2020 nihilism seems far less impotent. Much continues to be said—including by yours truly—about the specter of political violence in the United States. While there were attempts to make the horrific, heart-wrenching killing of Iryna Zarutska, into an aspect of this equation, it did not and does not particularly fit the bill in this case. The motivation for her murder was quite possibly racist, but it was almost certainly also thanks to untreated mental illness and a failure of institutional authorities to, at the very least, keep track of the most dangerous elements of our society (that is, a man with fourteen arrests, many for violent crimes, on his record). But ultimately, Zarutska’s killing was only as political as that of George Floyd’s: solely based on how it would be subsequently framed by the chattering classes and those invested in particular political outcomes or cultural grievances.

I was angry, of course, but upon reflection, I realized that what I felt was pain. A deep, resonant pain. And in that pain, was a very common realization: that this place that I believed would always be my true home might not really be my home anymore.

However, the murder of pundit Charlie Kirk made it clear that not only was his killing different, but that we, as a society, were likely overdue for a deeper self-examination of our current propensity for political violence and how, if I am not putting too fine a point on it, it is the descendent of the collective madness that peaked in 2020, but that has maintained a lingering, ambient presence. This is not about the particular politics at play; this is about how politics is being used; what it is justifying. Because, as I have stated elsewhere, and as Freddie deBoer has stated far better than I could, what defines our current era of political violence is less a concerted ideological project than a pervasive nihilism. I suspect that this nihilism was always there within all of us, but likely ignited with the ongoing failures of expectations that came from the ultimately misguided optimism of 2008 that Williams captures so well in Summer of Our Discontent, and informed the madness that peaked in 2020, and continues to inform our world today. While many of us recognized the true horror of that madness when it was happening, it is likely only now making itself apparent in this current crop of political violence. As deBoer wrote in his above-linked piece:

Where we are trained to see public violence as the outcome of ideology […] in the 21st century, a certain potent strain of political violence is not the product of ideology but rather an attempt to will ideology into being through violence itself. To create meaning in a culture steeped in digital meaninglessness by the most destructive means available. The 21st century school shooter (for example) does not murder children in an effort to pursue some teleological purpose; the 21st century school shooter exists in a state of deep purposelessness and, at some level and to some degree, seeks to will meaning into being through their actions. This is part of why so many of them engage in acts of abstruse symbolism and wrap their politically-incoherent violence in layers of iconography; they are engaged in cargo cult meaning-making, the pursuit of a pseudo-religion. The tail wags the dog; acts we have grown to see as expressions of meaning are in fact childish attempts to will meaning into being through violence.

This is, in my opinion, a perfect diagnosis of the moment in which we live. DeBoer has made many of those, and should be commended. But Thomas Chatterton Williams, in recognizing the collective madness that defined 2020 (but was, at least partly incentivized by the stressors of the past seventeen years), seemed to know where this was all going when he wrote the bulk of this book in 2023-2024. The data was there for him, but so was his powerful sense of intuition and, if one will pardon the term, moral clarity that led him to realize just what was at stake and say so in his brilliant book’s penultimate paragraph:

The long arc of the American moral universe, where it may ultimately bend, has been warped grotesquely beneath the competing heat and pressure of the on- and offline movement for social justice and the right-wing illiberalism it both feeds off and nourishes. From the abnormally harmonious days of Obama’s [first] election, through the tumult of the pandemic, to the disruption of the Gaza encampments in the tense months preceding Trump’s third and most threatening bid for the presidency, one dismal truth that spans the political chasm has become all too obvious: a remarkable and increasing number of Americans believe themselves not only justified but entitled to resolve political disagreements by force if they sense themselves at an impasse.

To keep this as personal as I have made it throughout this essay, I will be the first to admit that my pretty persistent cynicism regarding human nature often veers into pessimism and indeed outright nihilism. But those are my bad days, and those seem to be fewer and further between. I cannot for the life of me imagine existing in a state where my nihilism is so ever-present that I see all consuming violence of those I see as evil as the only acceptable conclusion. Perhaps my life is too charmed for such fantasies (or plans), and perhaps a resigned hope is a luxury that the younger generations cannot themselves yet imagine, due to any number of factors they cannot control. Or perhaps it is simply a byproduct of getting older and rounding out my education as I become more intimate with the extremes of the human experience, to paraphrase Dan Carlin again. Then I remembered that rage I and so many others experienced during the pandemic and in the years that have followed and I realized it was through that rage that I ultimately developed such an aversion to the performative, violent nihilism that defines our age.

While I worked on this essay, I did, in fact, recall a moment where I had little trouble choosing not to stew in nihilistic rage. It was in the late spring of 2020 and, paradoxically, it was in the midst of experiencing a moment of rage. I remembered it was when I saw the flippant and jubilant Facebook posts from supposed friends as the riots began to engulf my hometown. There is a frequently-used idiom that doesn’t really seem to have lost its power—seeing red. And yet, that did not happen with me. I experienced what I can best describe as white lightning; behind my eyes, creating flashes, and in my ears, mounting like a roaring wind tunnel. It felt somewhat like a panic attack, but I immediately realized it was not; I did not feel like I was spiraling out of control or falling into a pit, and I did not break out into a cold sweat. On the contrary, while panic feels like a spiral, this felt like a perfectly clear lake, despite the fact that my breath was short and my hands were shaking. It is hard to describe, but it was one of those few moments that one experiences perfect moral clarity. I was angry, of course, but upon reflection, I realized that what I felt was pain. A deep, resonant pain. And in that pain, was a very common realization: that this place that I believed would always be my true home might not really be my home anymore.

But then, eventually, I realized there was no reason for me to dwell with that kind of pain; it is indeed a common experience for many of us. It is necessary. As Thomas Chatterton Williams reminds us with his book’s epigraphs, Camus once told us that he had “seen people behave badly with great morality.” I was witnessing such a paradox unfold 3,000 miles away in my so-called true home. I would not let such people into my home, and yet there they were. So why, I wonder, would I consider such a place my home? The answer was self-evident.

I wouldn’t.

A powerful essay on a moment in time when a large portion of America slipped into collective madness. Worse, our institutions celebrated and amplified that madness.

Brilliant. This connection between memory and history makes me wonder so much.