India and the Human Triumph

A letter exchange with Claire Berlinski on poverty in India

Claire Berlinski is an essayist and the editor of the newsletter The Cosmopolitan Globalist as well as the author of the books There Is No Alternative: Why Margaret Thatcher Matters and Menace in Europe: Why the Continent’s Crisis Is America’s, Too.

Claire,

As I related in my recent essay on sexual violence in India, when I moved to the country in 2012, I had planned to spend my first few months kicking back on a beach in Goa but ended up homeless on the streets of Mumbai. I saw children maimed by the beggar mafias, lepers like the ones I had only previously known in the pages of the Bible, and the dismal sea of the Dharavi slums. It was human damage of a kind and on a scale that felt more like war than a regular state of being.

It therefore soothes the soul to learn that such a large portion of the human family is better off today than it was when I lived there. This month, Brookings Institute reported India has eliminated extreme poverty, citing the nation’s consumption expenditure survey, India’s first official survey-based poverty estimates since 2012.

The report says that between then and 2023, rapid economic growth and plunging inequality have driven the percentage of people living on $1.90 per day PPP from 12.2% down to just 2%. Urban poverty is down to 1%. The two authors of the report wrote, “In the annals of inequality analysis, this decline is unheard of, and especially in the context of high per capita growth.”

In 2019, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said China lifting more than 800 million people out of poverty was “the greatest anti-poverty achievement in history.” But I disagree. China’s destitution was thanks to the failed policies of Mao Zedong and the Communist Party, so the CCP gets no credit for removing its boot from the nation’s throat. But a great deal of Indian poverty can be laid at the feet of the British. India gained its independence in 1947 and its GDP per capita began skyrocketing just three years later, so all the beautiful bouquets belong to Bharat.

Recently, 415 million people exited poverty over a mere 15-year period ending in 2021. Roughly 121 million were lifted out of extreme poverty since 2011, Karan Bashin told me, a graduate assistant at my alma mater the State University of New York and one of the authors of the Brookings report. Bashin added:

In April of 2022, we had an IMF working paper titled “Pandemic, poverty and inequality: evidence from India.” There we had updated India’s poverty estimates and found it to be too low. We weren’t surprised to see the latest data but when our working paper came out, many found it difficult to accept the estimates. The official survey just confirms what we had argued in our 2022 working paper. The biggest reason for the eradication of extreme poverty in India is the massive expansion of India’s social welfare system, which was robust even during the pandemic. That was a big surprise more than anything else, to be honest.

The number of toilets, access to electricity, modern cooking fuel, and piped water have all dramatically increased. The report notes that in August 2019, for instance, roughly 17% of rural areas had access to piped water compared to roughly 75% today. I asked Baskin why the impact of expanded social welfare was such a surprise. He said:

Conventional wisdom at the time of the pandemic was that it had increased poverty in India. We too expected that pandemic-induced income stress would have temporarily increased poverty levels in India. But the Government of India during the pandemic had doubled the amount of transfers (subsidies) to the bottom 50% of India’s population.

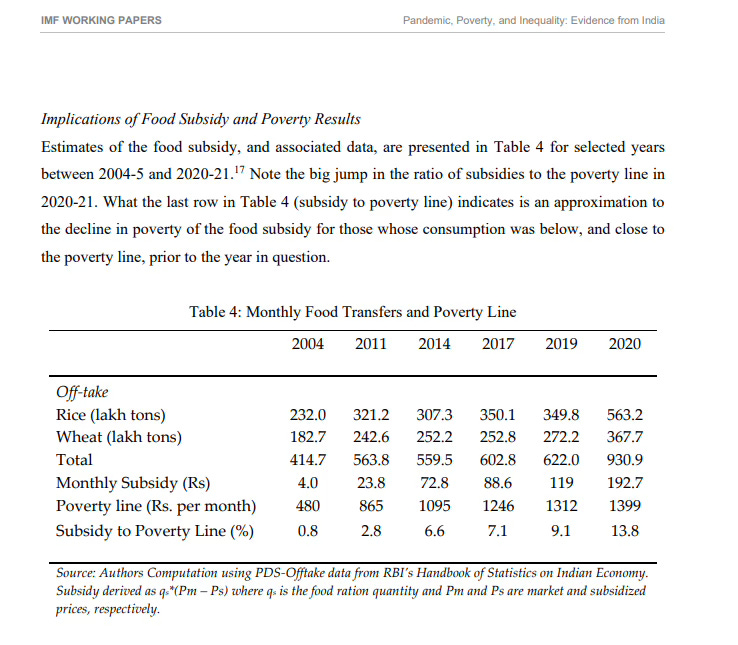

The table above from Bashin’s 2022 working paper shows that subsidies rose to as high as 14% of India’s poverty line in 2020, absorbing the bulk of the pandemic’s impact on the poor and subsequently preventing an increase in poverty, which has been declining in India since the late 1970s. But this trend has accelerated in the last decade, so I asked him how much credit the Modi administration deserves. He replied:

India’s existing social welfare system has been broadly the same for the last few decades. In 2013, India had a new legislation called the Food Security Act. This was before Modi’s administration. The big difference that Modi made was in terms of reducing corruption in the system.

They used India’s unique identity program to eliminate duplicate and non-existent beneficiaries, which allowed them to better target the poor. In terms of the decline in poverty, poverty in India has indeed been on a decline since 1970s.

However, at the higher poverty line India saw the same magnitude of decline over the last decade than in the past 3 decades. That decline is largely driven by strong inclusive growth experienced over the past 10 years. Incidentally, consumption inequality has also declined for the first time in India over this decade.

Now this accelerated decline in poverty, and decline in inequality, is largely in response to economic policies adopted since Modi became the prime minister. Some of these include the construction of 90 million toilets, giving 60 million households access to modern cooking fuel, ensuring that the remaining one-third of the country got access to electricity, and more recently, improving access to piped drinking water from 17% to about 75%.

You told me, Claire, that you once imagined such a change taking place and thought to yourself that if it did, “That would be the biggest advance in human rights and dignity that humanity has ever seen.” I couldn’t agree more.

China’s population is approaching a demographic crash. The geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan says it will happen this decade. When it does, India will aim to fill the manufacturing vacuum left behind. Several months ago I was chatting with Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan, the former head of trade and commerce at NITI Aayog, the top economic think tank for the government of India, and at one point I asked him about India’s potential to supplant China as a major manufacturing hub.

Despite all geopolitical tension, Gopalakrishnan said, no one can beat China. Many Chinese suppliers have talked about moving to Vietnam. Some have already done so. Vietnam’s government is willing to bend over backwards to accommodate investors, unlike Beijing, which basically tells investors to bend the knee or screw off. Not to mention rampant IP theft, tension with the U.S., and a looming tsunami of sanctions if China invades Taiwan. Suffice it to say, business owners are looking elsewhere. But Vietnam has shoddy port infrastructure, ranking 80th worldwide compared India, which ranks 51st and China 49th as of 2019.

The problem with India, Gopalakrishnan explained, is that it has an infrastructure deficit so its government nudges businesses to set up shop in undeveloped regions such as Kashmir. India has to be more flexible and let companies go to Bangalore if they want to go there. After all, many young tech employees generally prefer to live in bustling cities, not remote and isolated regions however stunning they may be.

Still, I am bullish on India. Its population is projected to dodge the demographic collapse that will slam China, it is home to a thriving democracy and a workforce that costs one-fifth that of Chinese labor. On the other hand, India is a bit of a mess when it comes to taxation, red tape, paperwork, and stubborn traditionalism. “India is a huge player, much bigger than before,” said Gopalakrishnan. “Comparing India to India of the past, we’re winning. But compared to China, we’ve got along way to go.”

But get there it eventually will. If you think of the story of humanity as a novel, India’s population means it is almost one-fifth of the book. I have always felt that this makes taking an interest in India almost a requirement, so far as one cares to read that book. And when the latest pages of that chapter tell of a tragedy turned happy, that isn’t just a great thing for over 17% of the planet’s people.

That’s a great thing for people period. It means we are solving the problem of poverty one step at a time. Wars are less frequent, crime is less frequent, natural disasters kill fewer people that ever before, medical science is advancing against all manner of disease, and global poverty is shrinking year by year. India’s defeat of extreme poverty is not just a win for the nation, but a human triumph.

I appreciate a good news story about India. I've personally seen improvement in infrastructure, healthcare delivery and health education in rural Tamil Nadu from local and gov't efforts over the last 10 years. It's an incredible country with big problems and glories like many others.