600 Million Hearts of Stone

India's rape culture is being ignored

They say the great god Indra once made love to the most beautiful woman in the land by disguising himself as her husband. Her name was Ahalya, and when her husband the sage Gautama Maharishi discovered the truth, he cursed them both and Ahalya was turned to stone for the crime of being raped. I don’t recall where I first heard this story but I remember thinking when I heard it, was this India’s first honor killing?

Later in the pages of the Ramayana, I learned that the Dandaka Forest was formed when King Danda raped Araja, the daughter of Shukra, who then destroyed Danda’s lands and turned them into a wilderness. Ever since I have carried this image in my mind of the beleaguered women of India with their hearts turned to stone and their minds made a wilderness as a result of the ways of men.

When I first arrived in India, I had only about a hundred dollars on me along with several thousand dollars worth of Israeli shekels that I had planned to exchange. My U.S. currency barely got me into Mumbai from the airport and a dinner. Looking back, I would’ve skipped dinner had I known that no one in India would accept shekels. I went to hotels promising to pay them richly if they but let me phone my parents. They thought I was a scam artist. I went to a church and asked if I could use the phone or rest a spell. I had been up all night, frantic, exhausted, worn thin. May I at least have a glass of water, I asked. The Father sighed deeply, annoyed, and moments later came back with a cool glass of water that I drank as slowly as I could to prolong the time I had to rest my legs.

I ended up homeless on the streets of Mumbai. I had plenty of money and nowhere to spend it. I befriended a chai walla, or chai street vendor, who let me store my backpack in his cart for safe-keeping. During the day, I walked around looking for help. I never ventured too far because my phone died on the first night and Mumbai is huge and I feared not being able to find my way back to my friend. In the evenings, I learned to make chai. To this day, I make a pretty mean cup. But the nights were the hardest part, when the hopeful wandering of the day was done and its hope was spent, and there was nothing left but to lay on the street alongside a row of other men, my heart full of sadness and the hopelessness of not knowing how I would ever get out of this situation, as well as the fear that someone might attack me in the night. I cried myself to sleep more than once.

Days passed. Then weeks. Eventually, I blindly wandered into a more touristy part of the city where I crossed paths with an Israeli tourist who was on his way back home. He gladly took my shekels, gave me U.S. dollars in exchange, and I was on the next train out of Mumbai. Perhaps some people would have hurried home. Perhaps some would have left India never to return. But I had come to India for the same reason I first went to Japan and Korea and China—to know its people, to understand its culture, and to learn its history. I knew, having learned from experience, that such a task takes months if not years. India would take at least a year just to penetrate the surface. So I began to drill deep. I studied the language, the music, the faiths, the literature, the food. I studied yoga in Rishikesh. I studied meditation in Dharamshala. Most of all, I tried to understand the ways of the people. In the end, I lived in India for three years, spending some of that time in neighboring Nepal.

If India is anything, it is grand. It is not a place you can visit for a few days or even a few months and come away hoping to understand it. I spent years there and still would not claim to have grasped its wonders. But I did fall madly in love. I have always believed that if you leave a country hating the place, the problem most likely lies with you. In any event, homelessness in Mumbai was not my only negative experience in the country, and reflecting on this, perhaps one of my greatest grievances with my beloved, adopted Mother India is the plight of women in that land.

My grandmother Millie didn’t use the word itself, but she was the first feminist I ever knew. She instilled in me a fiery outrage for the way women are often treated in this world. She herself was a victim of horrific physical and sexual abuse, including at the hands of her own husband, my biological grandfather, whom I have never met because she beat him back one night, packed her things, and took her five children with her. She later married an Italian man named Anthony, or Tony, and he was the only grandpa I ever knew on that side of the family. And that was just fine by me.

Thanks to Millie, if you were to browse my journalistic career, you would notice that the issue of women’s rights is a constant theme. I never go to a country without wondering what life is like for the women who live there. Often I speak to them and if I can, I befriend them and hope they will share with me their stories.

And this brings us to India.

Yesterday I came across a disturbing post on X about a Spanish couple that visited India. This past Friday, the woman and her husband were attacked in the Dumka district of India’s eastern state of Jharkhand, where they were tent camping. They both later posted a video in which both their faces were covered with cuts and bruises and the woman was choking back tears as she explained what had happened. The post read, “11 hours ago they announced they were at the hospital because he had been beaten up and she had been gang raped by 7 men.” Four men have since been arrested. Upon seeing their post, I reposted with the following remark.

The level of sexual aggression I witnessed while living in India for several years was unlike anywhere else I have ever been. Once a total stranger, a British woman, asked to sleep in my bed and pretend to be my girlfriend on a train ride because a man walking by in the hall had licked her foot and she felt unsafe. I introduced a female friend to a young Indian man and instead of shaking her hand, he groped her breast, and when she became angry he became extremely hostile and I thought I was going to have to fight the guy. I never met a female traveler who had not been groped or assaulted or worse, even if they had only been in country for mere days. I love India. It is and always will be one of my favorite places in the world. But I have advised female friends who asked me not to travel there alone. This is a real problem in Indian society that warrants more attention and that I hope will improve in time.

This post exploded and in less than 24 hours has received 37 million views. Indian women writers, journalists, and activists shared their own stories. Indian men shared how they do not let their sisters or friends walk alone at night or how they recommend their foreign friends to travel in groups. Foreign women who have been to India shared how they were groped within minutes of landing in the country. Or how they were almost kidnapped. Or worse.

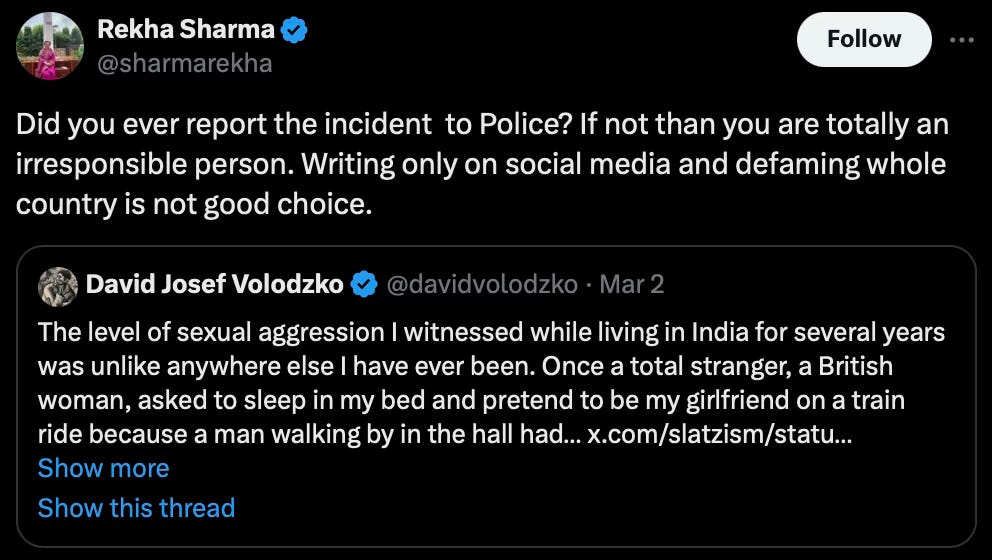

But not everyone appreciated my having raised the issue. Rekha Sharma, the chairperson of the National Commission of Women (NCW), a statutory body that advises the Indian government on all policy matters affecting women, later reposted my remark with the following comment.

I bristled a little but was not going to respond to this until an Indian friend suggested that I should also draw attention not just to the plight of women in India, but also to the abject failure of leadership to appropriately address this issue. I took their advice to heart and I replied as follows.

“Defaming whole country?” I literally wrote, “I love India. It is and always will be one of my favorite places in the world” and she accuses me of defaming India for addressing the plight of women in the country.

I also wrote, after someone who read my post made nasty remarks about India:

“Respectfully, you should be ashamed of yourself, sir. Yes, the situation for women is egregious. But let’s walk and chew gum for a step. The culture is one of the most richly beautiful and philosophically insightful of any I have ever seen. And I’ve seen most of them. Few cultures offer such bewildering depth or captivating beauty. It’s almost no wonder that enlightenment itself was conceptually conceived in these lands. And the food? And the music? And the nature? And, best of all, the people. Problems exist. I’m the last person you have to tell because I’m a strident critic of India’s flaws. As I am of Gaza, Korea, Israel, China, the US, Peru, and other places that I love. The places I do not love, I care less if they improve. Yes, problems exist. But so do the charms, and if you don’t know them, you don’t know India. In fact, I will tell you something more. I have already shared some of the awful stories of sexual assault in India, but of the many women I have met and come to know as friends in India, all of whom had such experiences in one way or another, not one ever concluded that India was a shithole worth nothing. To the great credit of these wise women, they saw the horror more directly than you or I, and the beauty. None became bigots. None walked away despising Indian people on the whole. None determined to snort at their entire culture. And thank God, because it would have been their loss, not India’s. The issues regarding treatment of women are only the tip of the iceberg, to be frank. There’s a lot of ugly to discuss of India. This contradiction seems to be confusing many people in my replies. Welcome to India. But although some countries are perhaps as beautiful, none are more so.”

And yet @sharmarekha says I am “defaming” the whole country.

This is what you get from NCW types. I am not Indian, so take my view for whatever it is worth, but my Indian friends do not seem to have much respect, if any, for NCW and one reason for this is because it has a deplorable habit of blaming women when they are attacked, raped or even murdered. NCW makes India less safe for women when it does these things.

Sharma herself has faced criticism for failure to respond to complaints filed by women’s rights groups over credible allegations of women being publicly stripped naked, beaten by mobs and raped in public.

And yet here she is with the gall to accuse me of defaming India. Ms. Sharma, it is you who defame India by presiding over a group called the National Commission for Women and doing nothing about the issue noted above, and then criticizing people like me for drawing attention to this important matter.

I love India. I don’t have enough heart to hold all the love I have for India, nor enough words to express it. But do you?

Now that you’re caught up on all the X drama, let’s take a closer look at the issue of rape in India. First, we must understand how prevalent rape is in India and the trajectory of that prevalence. But already we hit a wall because the first question is virtually impossible to quantify given various factors within Indian culture. Women simply do not usually come forward with accusations. To name but one factor, India, along with Pakistan and Nepal, are home to some of the highest rates of honor killings in the world.

This means that if a woman does come forward then she might also be murdered by her own father or brother for the crime of being raped. There is no way to know just how powerful a chilling effect this has. Or how many tens of thousands of cases are backlogged in police departments. But consider that according to India’s National Family Health Survey, 80% of victims never talk about the matter. Or consider that Hyderabad, the fourth-largest city in India with a population of 7 million people, had only 64 cases of sexual harassment reported in 2022. Kolkata, the seventh-largest city, had 25 cases. These are the official police numbers. Something is missing here.

The simple fact is, rape in India is out of control and we have no reliable figures on the scale of the problem. But we do know it is getting worse. In fact, reported cases alone have increased from 18,359 in 2005 to 31,516 in 2022. But again, these are just reported cases. Making matters worse, the conviction rate for rape can be as low as 27.8%. And then you have individuals such as Rekha Sharma and others who are so nationalistic that they would rather protect their sense of misguided patriotism than the people of India themselves—and attack those trying to help as being anti-India.

There are many brilliant and incredibly brave activists and journalists keenly focused on this issue. Despite the bad news, they are making good progress. For instance, the Mumbai-based nonprofit SNEHA (Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action) sends its people to Dharavi, one of Mumbai’s largest slums, where they distribute contact information for some of the services they offer, which includes counseling as well as legal and medical services.

But the problem is outstripping their ability to address it. In addition, there are pernicious beliefs and rape myths in Indian culture that condone the crime itself, such as blaming the victims for wearing Western clothing or for angering men.

This is a failure of education and community support, but also a much deeper problem, a problem of culture. Women must be encouraged to come forward and protected from the repercussions of doing so, but to make that possible will require profound changes that could take decades to cement. In the meantime, this beautiful land is becoming a wilderness of stone hearts.

The hatred and violence toward women in India is devastating. On my yearly visits to South India, I hear stories of local women abused by their husbands without any ability to leave. This is life for many there and the sexual violence toward women is another layer of this violence entrenched in a culture often ironically devoted to the many forms of Divine mother.

A former co-worker was raised in India by her wonderful educated free thinking mother. When I first met her, she told me how she was taught to fear the train system , carry a weapon and never travel without a male escort. And that was 30 years ago.