A letter to Curtis Yarvin on monarchy

Curtis Yarvin, who writes under the pen name Mencius Moldbug, is the author of the newsletter Gray Mirror and an advocate for monarchy.

Dear Mencius,

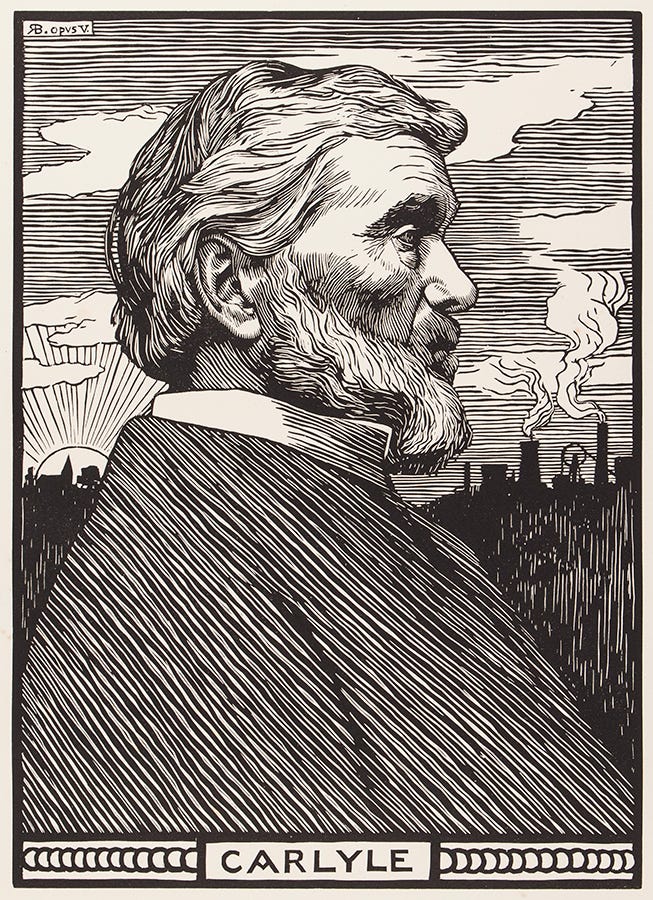

Thank you for taking me up on the challenge to discuss monarchy and democracy at a time when authoritarian rule is ever on the rise and democracy ever more in peril. What I have found in reading your work, perhaps even more than an argument for monarchy, is a celebration of the writings of Thomas Carlyle, by whose pen many of your own ideas have clearly, and with your own admission, been inspired. The unread Victorian sage, as he has been described, deserves far more attention than he finds and far more shade than he catches. Like you, I adore the warm candlelight of his prose. But less so the man’s philosophy. Bear with me as I tell you things you already know, for the sake of readers who may not, since Carlyle offers an invaluable light with which to illuminate the contours of your own thinking.

Into the Carlylean Abyss

“If there is one writer in English whose name can be uttered with Shakespeare’s, it is Carlyle,” you once wrote. It’s actually Milton, if we’re only allowed one, but that is not to diminish Carlyle’s considerable contributions. One of the greatest works the Scottish essayist ever produced was the 1837 history The French Revolution, and it was a revolution in its own right. His friend, John Stuart Mill, had found himself unable to complete the project and handed it off to Carlyle, who delivered the three-volume work more in the manner of an epic poem than a dry historical account. The pages cry with beauty. Unlike historians in another way, he made his feelings about affairs transparent, roundly condemning the French Revolution and hoping fair England would find a way to avoid such ruin. His reflections are sadly prophetic, as we face a new revolution from the left in the form of woke alphabet racism. Carlyle believed such bullshittery never lasts, and said this of the fall of the Ancien Régime:

Where this will end? In the Abyss, one may prophecy; whither all Delusions are, at all moments, travelling; where this Delusion has now arrived. For if there be a Faith, from of old, it is this, as we often repeat, that no Lie can live for ever. The very Truth has to change its vesture, from time to time; and be born again. But all Lies have sentence of death written down against them.

Carlyle’s influence was profound. Charles Dickens used the book as a reference for A Tale of Two Cities, Oscar Wilde declared Carlyle had “made history a song for the first time in our language” and proclaimed him the English Tacitus. He even tried to buy the table on which Carlyle had drafted the masterpiece. Ralph Waldo Emerson adored the book. It was reportedly the last thing Mark Twain read before he died. And Martin Luther King, Jr. often quoted the famous line above, “No lie can live forever.” In our time, we already see the lies of biological denialism and anti-racist bigotry unraveling. So there is no mystery in his appeal. The power of his language sits on display and hits with ringing poetic and philosophic force, as when he writes:

There are depths in man that go the length of lowest Hell, as there are heights that reach highest Heaven; — for are not both Heaven and Hell made out of him, made by him, everlasting Miracle and Mystery as he is?

But we have the immaculate poetry of Ezra Pound, who praised Hitler and called Jews “filth,” as well as the phenomenological brilliance of Martin Heidegger, a member of the Nazi Party, to remind us that no matter how great a poet or philosopher is at their craft, some of their ideas may yet be garbage, if not downright evil. I think G.K. Chesterton explained Carlyle well in The Victorian Age in Literature:

He himself was much greater considered as a kind of poet than considered as anything else; and the central idea of poetry is the idea of guessing right, like a child … His great and real work was the attack on Utilitarianism: which did real good, though there was much that was muddled and dangerous in the historical philosophy which he preached as an alternative. It is his real glory that he was the first to see clearly and say plainly the great truth of our time; that the wealth of the state is not the prosperity of the people.

Chesterton is correct. Carlyle wrote beautifully, and for this reason was an exhilarating historian. He was also an insightful and witty critic, especially of the corruption of the state and the delusions of the masses. He excelled at raising questions, but not at offering answers. He knew how to swing a sledgehammer, but not how to lay a brick. Again and again, reading his work, as in reading yours, one finds the same problem, that of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Is democracy flawed? Then let us have dictatorship. Is freedom illusory? Then let us have slavery. Carlyle himself referenced the baby and bathwater idiom in his infamous essay on slavery, saying that we must not throw the slave out with the institution of slavery. But he did not mean get rid of slavery and spare the slave. Rather, he meant to get rid of bad slavery but keep good slavery, or as he put it, “to abolish the abuses of slavery, and save the precious thing in it.” You have to be a special kind of stupid to think there’s anything precious in slavery.

Carlyle compares slavery to marriage, saying that “in every human relation,” too much freedom is bad while commitment, or “continuance,” is good. The way to save slavery then, is by making slaves and slavers contractually bound. The slaves will thank you for it!

“Servants hired for life, or by a contract for a long period, and not easily dissoluble, so, and not otherwise, would all reasonable mortals, black and white, wish to hire and to be hired ! … The Germans say, “you must empty out the bathing-tub, but not the baby along with it.”

Jesus Christ. This is why Carlyle is indeed no Shakespeare. The Bard of Avon was one of the best writers in human history as well as a penetrating moral thinker, whereas Carlyle is one of the best writers of the Victorian Era as well as a moral moron. The idea that you can save slavery by adding rules is like saying that you can save rape by the very same means. What you get in the end is either no longer rape at all, in which case you are merely playing word games to conceal your childish intelligence, or you have not saved it in any sense, in which case you are merely playing word games to conceal your moral depravity. I leave it to the reader to decide which is true in Carlyle’s case.

Lipstick on a Dead Pig

As far as I can tell, you have made the same argument regarding slavery and dictatorship. Namely, that we can save slavery by simply adding rules. Maybe the slaves can agree to sell themselves. Never mind that only people in the most dire of circumstances would do such a thing. Never mind that slavery has harms that extend beyond the relationship of master and servant. Never mind that we must think of what will happen if and when such contracts go unheeded. Nor is it an adequate response to say, “Enforce them better.” Never mind that we already know exactly what such a world looks like.

You argue that we can save monarchy, or dictatorship, in the same way. Better rules. This argument is more compelling than the one for slavery. Instead of a dictator, you say, just think of it as a CEO. But are you playing word games? One of the reasons I wanted to speak with you was to discover the answer. Are you describing a dictator or a king, or are you describing a CEO, or a president, and simply using words like “monarch” because they’re clickbait? I have heard you argue that the king could be elected, and that they could be elected to four-year terms, and that the purpose of this king would be to project the power of the people upward in a system in which the people have little voice, but rather the illusion of a voice, in fact in a system in which even the political elites have hold little sway, though as you often note, at least they are aware of this reality, unlike the unwashed masses.

You have learned the best lessons from Carlyle, and I enjoy reading your criticisms of state power as well as when you kick your boot up on the bumper and look under the hood—the executive branch (which despite your claims, does exist) is arguably not as powerful as it should be, Congress is arguably too powerful, one’s job in politics is often not to do politics but to raise funds, even those whose asses warm the seats of power wield very little of it, and to fix this engine we need a stronger piston, i.e. a more powerful representative of the people. But why doesn’t unitary executive theory solve the problem for you? Or if you support a king who is elected to four-year terms, as you have said that you do, why do you object to a president? One reason to want a king or dictator would be so that they get more done, and are not interrupted by the fundraising election cycle. But once you have kings seeking election, the main difference seems to be their degree of power, and in this case, why not advocate for a more powerful president? After all, you argue that nations should be run like startups and their leaders should be like CEOs. Is a president not more like a CEO than a king?

But I wonder, have you also learned the worst lessons from Carlyle? Namely, when a revolution is afoot, seek monarchy. When the people rise up, get a bigger boot to stomp them down. When the slaves break their chains, shackle them with contracts.

Revolutions and Revolutions

This brings me to an other problem with Carlyle. My objection to his writing is not with his refutation of the ruins of revolution, nor solely with his proposed solutions, but also in part with his diagnosis. He seems unable to discern that not all revolutions are the same. There was no widespread or systematic execution of the British in the wake of the American Revolution. Nothing to compare to the Terror of its French counterpart, in which the Committee of Public Safety took the lives of some 40,000 souls. Back across the pond, there were isolated exceptions, such as the Battle of Waxhaws in 1780, during which American forces under Abraham Buford were overwhelmed by British troops in the command of Banastre Tarleton and allegedly subjected to abusive treatment and summary executions when they surrendered. But on the main, both sides followed established conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners of war. I see no such acknowledgment in Carlyle:

The world is all so changed; so much that seemed vigorous has sunk decrepit, so much that was not is beginning to be! — Borne over the Atlantic, to the closing ear of Louis, King by the Grace of God, what sounds are these; muffled ominous, new in our centuries? Boston Harbour is black with unexpected Tea: behold a Pennsylvanian Congress gather; and ere long, on Bunker Hill, Democracy announcing, in rifle-volleys death-winged, under her Star Banner, to the tune of Yankee-doodle-doo, that she is born, and, whirlwind-like, will envelope the whole world!

He reacts to the American Revolution like he does to the French. It is a revolution, a disruption of the order of things, and therefore we must respond with greater Order. Once when you were asked why you support monarchy, you replied quite simply, “Because I like order.” I am with you there, and I find the calamity and death that comes with many revolutions, was well as their attendant ideological justifications, nothing less than evil. But other revolutions I support. Do you not also see that revolutions vary in type and moral value, or do you think any upheaval of the status quo is more harmful than the alternative?

And what is the alternative to revolution? In Carlyle’s mind, it is for the kings to remain vigorous so as not to fall prey to the Yankee-doodle public. Kings will die, he notes, “and the rolling and the trampling of ever new generations passes over them, and they hear it not any more forever.” But though they fade, the glory of their reign remains as a testament to the progress they ensured. “Stone towers frown aloft; long-lasting, grim with a thousand years” and “Labour’s thousand hammers ring on her anvils.”

More than this, we have the labor of science, the cunning craftsmen who have been “yoking the winds to their Sea-chariot, making the very Stars their Nautical Timepiece,” or highest of all, those who have “written and collected a Bibliotheque du Roi; among whose Books is the Hebrew Book!” This is because, Carlyle felt, the best of all progress was the development of ideals, Church and Kingship, and these because they established their Credo and gave themselves something “worth living for and dying for” in this “vague shoreless Universe.” But like castles and kings, even the best ideals fade.

But of those decadent ages in which no Ideal either grows or blossoms? When Belief and Loyalty have passed away, and only the cant and false echo of them remains; and all Solemnity has become Pageantry; and the Creed of persons in authority has become one of two things: an Imbecility or a Macchiavelism? Alas, of these ages World-History can take no notice; they have to become compressed more and more, and finally suppressed in the Annals of Mankind; blotted out as spurious,—which indeed they are.

Here he alights upon a powerful truth. In a time with no ideals, much like our own as we find ourselves knee-deep in the postmodern mud, then people in power tend to be imbeciles or Machiavellian, and we are better off blotting out our memory of such ages. They, like the poor wretched souls who lived in them, are lost to time. The Church, which once “could make an Emperor wait barefoot, in penance-shift; three days, in the snow, has for centuries seen itself decaying” while the King merely hunts for sport and “when there is to be no hunt … will do nothing” and merely idles because “none has yet laid hands on him.” The people are in no place to rule either, he adds:

Such are the shepherds of the people: and now how fares it with the flock? With the flock, as is inevitable, it fares ill, and ever worse. They are not tended, they are only regularly shorn … They are sent for … to fatten battle-fields … with their bodies, in quarrels which are not theirs … Untaught, uncomforted, unfed; to pine dully in thick obscuration, in squalid destitution and obstruction: this is the lot of the millions.

Carlyle is of course narrating events in France, but I know you will agree that this sad scene describes many nations at many times, including ours today. This makes the role of the Poet Critic, as I consider you to be, invaluable. Where I think you go wrong is where Carlyle goes wrong. The Poet Critic is not the Philosopher.

To show you what I mean, anyone who reads The French Revolution, by God I hope, is struck with the terrible question—how do we avoid the calamity of ruinous revolutions? Four years after his book he published his 1841 collection of lectures On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, in which Carlyle argued, “Great Men should rule and that others should revere them.” Of course, no one agrees on who the Great Man is, hence the need for democracy. Sometimes even when we agree upon a Great Man, he proves himself a dangerous fool, hence the need for democracy. You can try to fix monarchy by making it democratic, but that only proves the point.

The Everlasting No

Some of this line of thinking was adopted by Friedrich Nietzsche in his conceptualization of the Übermensch. Carlyle famously wrote, “The History of the world is but the Biography of great men.” Even here he is only half right. It is true that great men can change the course of history. But they are also subject to factors beyond their control. Had Elon Musk been born to a Dalit family in India, he would not have risen to such heights. No one takes the great man theory of history seriously when it is presented on its own, without the context of time and place, and the facts of social history, or what we call “history from below.” Great Men are tsunamis, but the people below make up the sea itself.

I see the great man theory at work in your political science, but do you also acknowledge history from below? In “The Ancestry of Fascism,” Bertrand Russell wrote of Carlyle’s 1843 work Past and Present:

Those who still think that Carlyle was in some sense more or less Liberal should read his chapter on Democracy in Past and Present. Most of it is occupied with praise of William the Conqueror, and with a description of the pleasant lives enjoyed by serfs in his day. Then comes a definition of liberty: “The true liberty of a man , you would say, consisted in his finding out, or being forced to find out, the right path, and to walk thereon”...He passes on to the statement that democracy “means despair of finding any Heroes to govern you, and contented putting up with the want of them.” The chapter ends by stating, in eloquent prophetical language, that, when democracy shall have run its full course, the problem that will remain is “that of finding government by your Real-Superiors.” Is there one word in all this to which Hitler would not subscribe?

Russell was more right than he knew. Hitler and Goebbels adored Carlyle’s writings against democracy and in favor of strongmen governments, in fact Goebbels read passages of Carlyle’s six-volume History of Frederick II to Hitler in his bunker during their final days. May all strongmen go out in similar fashion.

A few more things should be said of Carlyle, particularly for readers who do not know him. He was a great inventor of phrases, and gave us many expressions we use so often that almost none of us now understand they come from him. He coined the phrase the “meaning of life,” writing “yet is the meaning of Life itself no other than Freedom.” He coined the phrase the “dismal science” to describe economics in his 1853 essay “Occasional Discourse on the Nigger Question,” in which he critiques the British abolition movement as hypocritical. Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and slavery in 1833, but other nations did not and therefore stopping the trade is impossible, he argues, not to mention the conditions on most slave ships aren’t really so bad, so rather than setting the enslaved free and leaving them to fend for themselves in an unfamiliar world, slavers should keep their chattel — but treat them like house slaves. The essay was not well received. Carlyle’s friend, J.S. Mill, the same who had handed him the project The French Revolution, eviscerated him in an essay of his own.

For me, one of the best criticisms of Carlyle comes from a phrase he coined himself, namely “the everlasting no,” which was his name for disbelief in God, to oversimplify the matter. But it is more than this. The everlasting no is a rejection of the sublime in life. A rejection of the sacred in humanity. It is what would allow someone to think we should perhaps retry slavery or dictatorship, or even worse, it is taking pleasure in mocking and jeering at things of the highest value, such as freedom from chains, as if they are only valued by insipid fools who know no better. It is the curse of the Critic. The curse of the Poet Critic is that the everlasting no can sound sweet enough to sway.

David, you make me glad to be a subscriber. Thank you again.

Thank you for this essay.