Woke Education in America, II

NEWS

Biden administration announces additional $9 billion in student debt relief.

The U.S. Department of Education is launching a review of the Massachusetts special education system to determine whether the state adequately supports students with disabilities.

Florida Democratic lawmakers convened to address classroom censorship.

Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz noted Florida leads the nation in removing books from school libraries with over 1,400 titles taken off the shelves.

FEATURE

This week I spoke to the brilliant educator Kevin Ray. Kevin is deeply devoted to the craft, unyielding in moral principle and always thinking of the student above all else. I wish I’d had more teachers like him growing up. We didn’t touch on it but Kevin was recently featured by the National Review in the piece “Meet the NYC Theater Teacher Who Stood Up to ‘Anti-Racist’ Activists at the Height of the Moral Panic of 2020.”

We discussed the philosophy of teaching, how Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” has changed education in America, the harms of woke pedagogy, the tragic death of Richard Bilkszto after enduring genocidal rhetoric at the hands of a DEI trainer, and more.

REVIEW

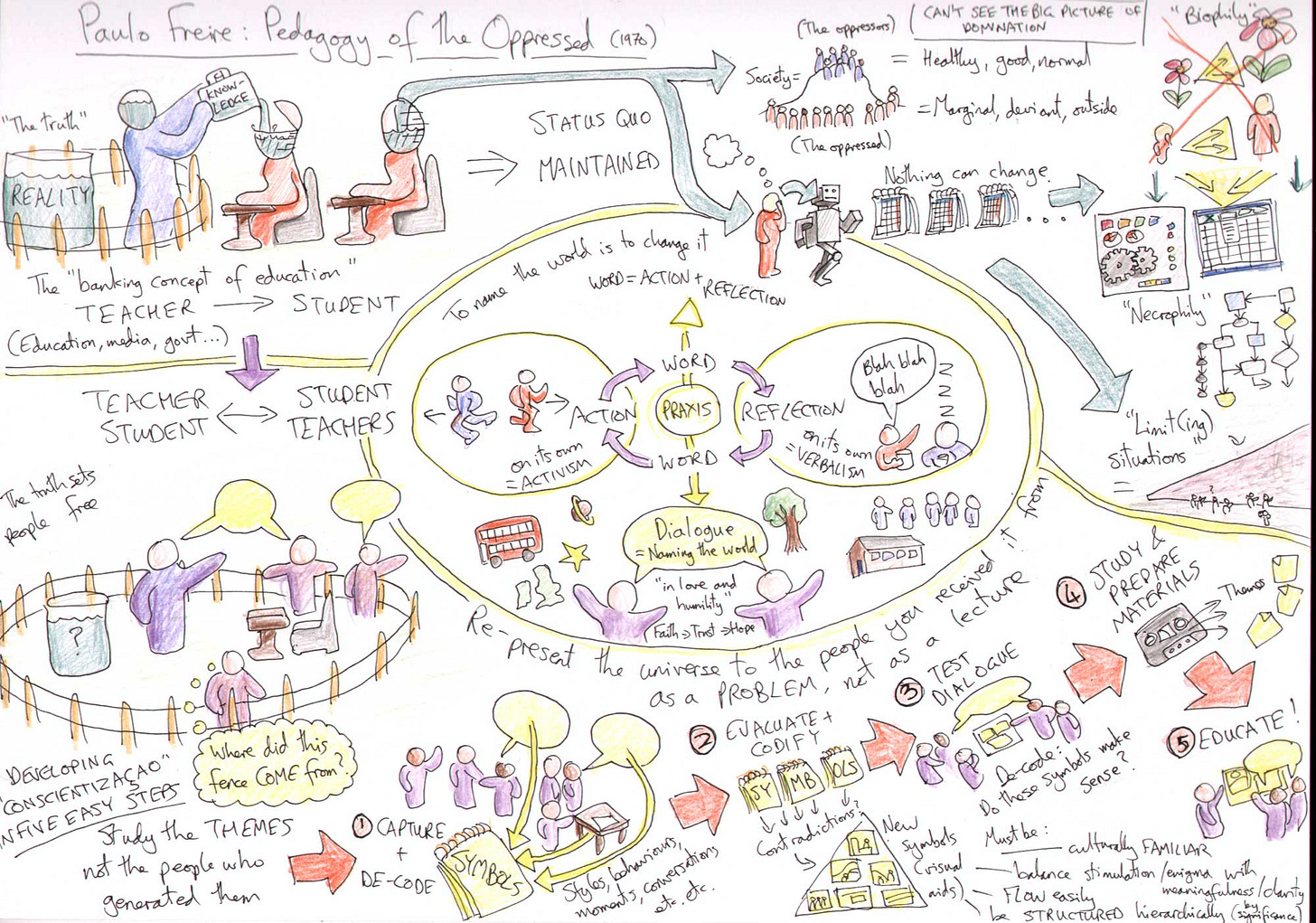

In “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Brazilian educator and Marxist philosopher Paulo Freire critiques the traditional “banking” model of education in which students are seen as passive recipients of knowledge. Freire instead advocates for a “problem-posing” approach in which students and teachers engage in a dialogue to create knowledge together. This analysis was groundbreaking at the time.

I have taught pre-school, elementary, high school and university classes and I have always tried to make the classroom learning experience as much of a dialogue as I can. There is a time and a place to have students sit back as the instructor holds forth, but students generally retain more when the information is presented in an interactive way, and the easiest way to make it interactive is to make it a conversation. So for his influence in making classrooms more interactive, we owe Freire a debt of gratitude.

And there is hard evidence to suggest the discussion method is more effective in certain situations. One 2015 study of Mayo Clinic medical students found that the discussion method “may lead to better practical knowledge and potentially improved long-term knowledge retention” compared to the lecture method. A 2021 meta-study of 30 selected articles found that 24 showed better results for the discussion method. On the other hand, a 2020 study found that among nursing students, the lecture method was best for immediate knowledge retention and was preferred by most students. Personally, I find wisdom in a 2008 study that concluded lectures are good for promoting basic knowledge while discussion and debate is better for developing student comprehension of complex topics.

The point is, both are valuable and both have their place in the classroom. But Freire didn’t think so. In his book, he claims the lecture method creates a dynamic in which the teacher “oppresses” students with knowledge. This, he argues, is because the teacher “deposits” knowledge into students as if they are banks, narrating without taking questions or allowing students to challenge or critically engage the information.

This is of course total bullshit. Teachers who use the lecture method do, of course, take questions and encourage students to critically engage the material. You do not have to sit in a circle to get students to ask questions.

Good teachers, or even just average ones, recognize that certain truths are dependent on context and perspective. Not to mention academic fields are always evolving so truth can sometimes be a moving target. Yet this is how Freire begins Chapter 2:

Education is suffering from narration sickness. The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalized, and predictable. Or else he expounds on a topic completely alien to the existential experience of the students. His task is to “fill” the students with the contents of his narration— contents which are detached from reality, disconnected from the totality that engendered them and could give them significance. Words are emptied of their concreteness and become a hollow, alien ated, and alienating verbosity.

He goes on to argue that the banking model reinforces the existing power structure and societal norms by not encouraging critical thinking, and that it dehumanizes both the teacher and students by trapping them each in a system of oppression, thus denying them their full humanity. He even claims that the lecture method is a form of colonialism because the dominant culture’s beliefs are imposed on the students and the students, again, are not allowed to ask questions.

I don’t entirely disagree with him. In fact, I agree with everything he says so long as we are talking about the environment he was living in when he came up with this stuff.

Freire’s early experience as an educator was in his hometown Recife in northern Brazil, where he taught illiterate adults. After the 1964 military coup, he moved to Bolivia, then Chile. He published his first book, Education for Critical Consciousness, in 1967. In this collection of essays, Freire emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and conscientização or consciousness. He argues that education should not be a passive process but an active one in which students engage with the material and learn to question the world around them.

Again, I support this approach to education, but the problem is when he starts to talk about the lecture method as not allowing question or critical thinking, and therefore oppressing students’ ability to reason, dehumanizing them, forcing another culture upon them. This may have been true of the way in which education was conducted in certain Brazilian schools from the 1930s, when he was a student, to the 1960s, when he was teacher. But does his argument apply to other places, such as the United States?

During the 1940s and 1950s, American education underwent significant changes as it became standardized and started to receive more federal, state and local funding. You might think standardization and traditional teaching methods such as heavy blackboard use, rote memorization and the lecture method meant students were not encouraged to ask questions or critically engage the material.

But this is not what we find. The teacher guidebook Questioning Skills, for Teachers, originally published by the National Education Association of the United States in 1982, has this to say:

Increased attention toward intellectual achievements developed following the successful Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957. Fearing that our academic programs were inferior to those of other countries, the federal government supported the development of a wide range of curriculum projects. The instructional strategies required to teach the new curricula emphasized the development of students' higher thought processes. These strategies, such as the inquiry approach, relied heavily on the teacher's ability to stimulate critical thinking skills through effective questioning behaviors.

In other words, the United States government was pushing the discussion method in the late 1950s, a full decade before Paulo Freire published Pedagogy of the Oppressed in 1968. His argument simply did not make any sense in an American context.

Plus, his argument was developed while teaching illiterate adults. Yet the English translation of the book was published in 1970, rapidly became a sensation among Marxist students of education who could now do “revolutionary” work in the classroom, and went on to lay the groundwork for the critical pedagogy movement in the United States, where it had a profound influence on figures such as Henry Giroux and Peter McLaren. Giroux, the author of Teachers as Intellectuals, is known for critiquing the corporatization of education and the influence of neoliberalism on educational policies. McLaren, the author of Pedagogy of Insurrection, is a Marxist educator who advocates for revolutionary pedagogy.

So just how widespread is critical pedagogy in American schools? For many people who get a bachelor’s in education with the goal of becoming an elementary school teacher, it’s required reading. As Giroux has said himself about Freire:

His book Pedagogy of the Oppressed is considered one of the classic texts of critical pedagogy and has sold over a million copies, influencing generations of teachers and intellectuals both in the United States and abroad.

This is not an academic matter. We have all seen the debates over wokeness in elementary schools. If you’ve been wondering why people who got into education end up treating toddlers like lab rats for their revolutionary political agendas, well, now you know. Much of it can be traced back to Freire and this book.

I despise book bans but if there was one book we might target to save the minds of our children, it would be Pedagogy of the Oppressed. At the very least, when they teach this stuff to education majors, honor Freire’s philosophy and make sure you teach it so as to get students to critically engage the text. Push them to challenge his ideas. Get them to ask questions such as, does his central tenet hold true? Does the lecture method prohibit student questions? Does this theory apply to other countries?

The last thing you want is to study Freire and end up turning your student into victims out of some misguided desire to liberate them, because then what you are practicing truly is a pedagogy of the oppressed.