Why blue-collar culture matters

It exemplifies indispensable virtues: dignity through work, independence through skill, and humility through service.

This essay was originally published in City Journal.

For more than a century, Hollywood and advertising have been the twin engines of American identity. Generations of boys found their blueprints for manhood on the silver screen, as girls looked to magazine models. Sitcoms enshrined the family’s form, right down to the color of the picket fence; and even love came packaged with a script, from meet-cute to the grand gesture and happily-ever-after.

Hollywood tells these stories because they sell tickets, not because they’re true. But America didn’t always get its sense of self from the same place it got buttered popcorn. Once, the national ethos came not from theater kids and Mad Men but from settlers, planters, and frontiersmen, who lived liberty and self-reliance as everyday truths.

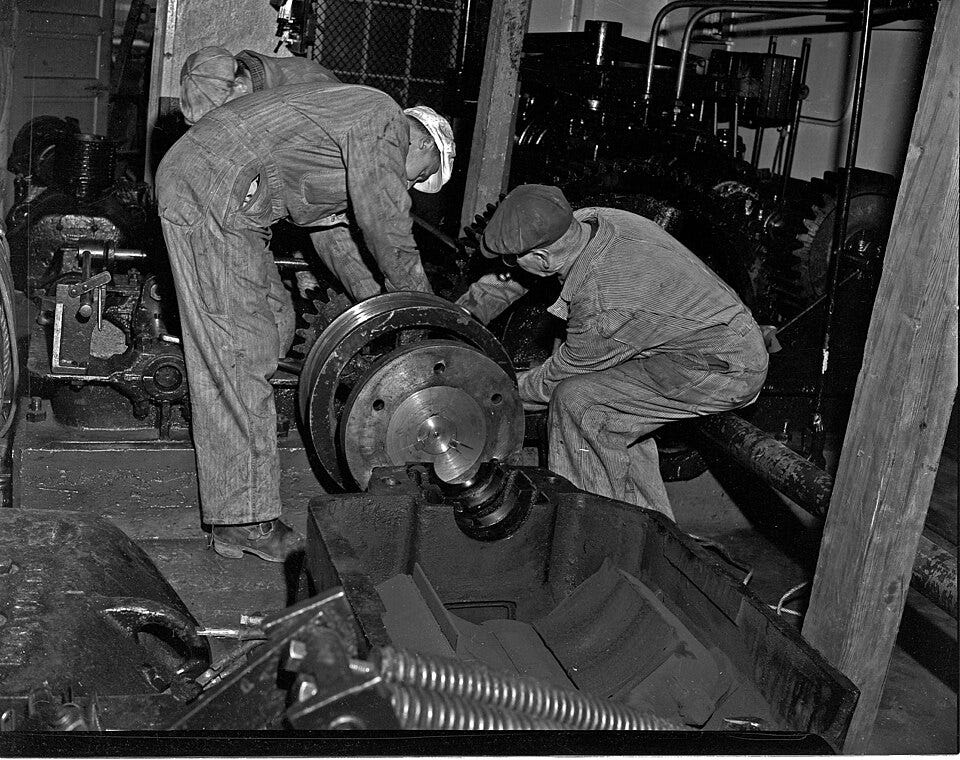

It was the Industrial Age that made America a superpower. And in that furnace, the modern American was forged, hauled into reality by the men and women who dragged timber, tarred roofs, welded steel, and shoveled coal—the backbone of American industry: the blue-collar worker.

Just as early settlers planted the seeds of liberty, blue-collar workers poured the moral concrete for the American house. And what did that mean? Rain or shine, finish the job. Your work is your reputation. Worth comes not from affirmation or pity but from being useful. Strive to be hammer-ready, hardworking, plainspoken, and humble. At the republic’s dawn, the independent farmer, owning and working his land, also stood as a cornerstone of American identity. Jefferson praised this agrarian vision, imagining a nation of small, self-sufficient farmers, while Hamilton argued for an urban, industrial economy.

By the early 1800s, the farmer still dominated American life, but artisans and craftsmen were rising, too—blacksmiths, carpenters, printers. They embodied self-reliance and skill. Boston’s Paul Revere had been not just a Revolutionary War figure but a master silversmith. Cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe shaped American furniture. Samuel Colt perfected the revolver—hence the saying, “God created men, but Samuel Colt made them equal.”

Then came the frontiersmen—Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett—carving lines into maps or blazing trails where no maps existed. If Europe was defined by court and cathedral, America was shaped by workshop and wilderness.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the nation urbanized, the lone pioneer gave way to the factory hand. Millions of immigrants poured in to cities, trading independence for assembly lines in mills, mines, and railroads. Just as Upton Sinclair depicted the brutal realities of factory labor in his novel The Jungle, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath has taught generations of readers since how the Great Depression both hardened and ennobled the worker. Dorothea Lange’s photographs of stoic farmhands and WPA murals of broad-shouldered laborers testified to their resilience. World War II recast workers once more—not only as laborers but as patriots, fueling victory abroad. Work was no longer just toil; it was a form of heroism.

By the mid-twentieth century, movies and television turned working-class life into dramatic material. Marlon Brando’s longshoreman in On the Waterfront embodied a rough moral code set against corruption. Rocky elevated a Philadelphia underdog into a universal symbol of grit. All in the Family brought dockworker communities into America’s living rooms.

The American worker had become the protagonist of the national story, a relatable counterweight to elites and professionals. The worker stood for straight talk and honest labor, which, along with liberty and self-reliance, came to define the imagined heart of the American people.

Politicians seized on the blue-collar figure as shorthand for “the people.” Advertisers followed suit: if a hardhat could sell dignity, he could sell trucks and beer, too. The image may have been cheapened, but even in an age when much labor has shifted to screens, spreadsheets, and symbols, the old virtues remain indispensable: dignity through work, independence through skill, and humility through service. Yet these values, once obvious, have faded from cultural prominence, overshadowed by celebrity, credentialism, and the cult of self-expression. What was once honored as common sense now often has to be argued.

Three things would help reinforce those blue-collar values, which would be salutary for a culture that too often seems to have forgotten them. The first is education. Schools have steered students away from the trades and into the narrow funnel of the four-year degree. The result has been a generation burdened by school debt, even as vital skills vanish and progressive orthodoxy spreads unchecked. Reviving vocational programs—shop classes, apprenticeships, trade schools—would restore honor to the men and women who build, repair, and maintain the country.

Second: civic respect. Too often, politics treats blue-collar workers as a demographic to be managed. But their labor still makes prosperity possible, and civic life should reflect that truth. Political rhetoric should recover the language of dignity in manual work as a measure of national health.

The third is storytelling. The stories we tell shape the values we hold.

Cultural recognition of blue-collar work survives in Buffalo and Detroit and Fort Wayne, and in many other places in the country—and it can be strengthened. Our cultural industries need not romanticize labor, but they should remember to respect it.

"The stories we tell shape the values we hold."

Ain't it the truth...I would add "shape and reflect the values we hold."

"the old virtues remain indispensable: dignity through work, independence through skill, and humility through service. Yet these values, once obvious, have faded from cultural prominence, overshadowed by celebrity, credentialism, and the cult of self-expression. What was once honored as common sense now often has to be argued." David love the above words, IMO fully capture the madness of the last 10 years.

Being in my late 50's and coming of age in the late 70's and early 80's the concepts of family, hard work and self reliance were everywhere in my childhood. The American story (good and bad) was told in way that forsted the bonds of civic engagement with our leaders and fellow American's. I plan to share the essay with my kids and hope to engage in meaningful conversation at our local coffee shop especially with the ones with college degrees :)