Untranslatable

Four years after the El Paso shooting

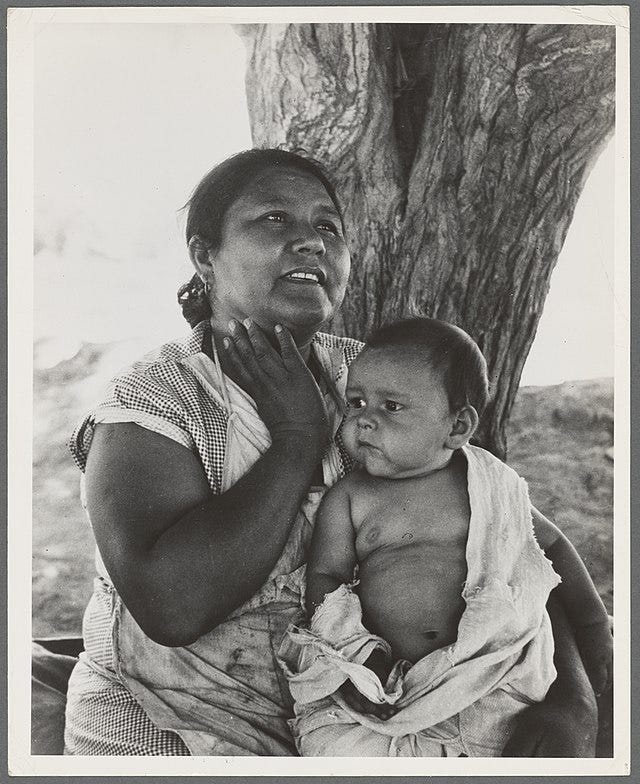

“Sometimes I tell my children that I would like to go to Mexico, but they tell me ‘We don’t want to go, we belong here.’” —Mexican mother in California, above, 1935

“In English my name means hope. In Spanish it means too many letters.” —Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street

Four years ago, I picked up a newspaper and read a story about a group of people. You can read about them if you wish but I am not going to divulge the sacred details of their lives here. Instead, I want you to imagine knowing one of them, as I did when I read the story.

They say anyone who comes to America can be American. It’s not like that most places. You can learn to speak sparkling Japanese and wear yuakata every summer, drink enough green tea to fill the Shinano River, become a legal citizen and live there for 50 years yet you will never really be Japanese. But come to America, embrace it as your own, and you are one of us.

What they don’t tell you is you are also and forever in the purgatory of the intercultural lacuna. The lacuna is what translation experts call the linguistic gaps, the untranslatables, like how in English we have no masculine or feminine articles such as el or la. That gap is the lacuna, what Wikipedia calls “a tool for unlocking culture differences.”

What they don’t tell you is you become that tool. When you move to El Segundo Barrio as a young girl and you have to stand in front of the classroom and introduce yourself in broken English, the Americans giggle and tease. But later they want to know things about your home. They want you to tell them how to say things in Spanish. You are now the lacuna, their tool for unlocking the mysteries of Mexico.

People love lacunas. There are dozens of articles online listing all the untranslatable terms. Danish hygge, Korean han, Hebrew firgun. In Finnish there’s a word to describe the joy of sitting on a bouncy cushion—hyppytyynytyydytys. People love reading these things. But no one wants to be a lacuna. Yet here you are. An untranslatable.

After enough time and hard work and many nights spent crying yourself to sleep thinking your English will never be good enough, that you will never fully fit in, never have friends and never get married, your English gradually improves. You do make friends. You watch the shows and eat the food and wear the clothes and soon none of the cultural references go over your head anymore. You get all the jokes now. Your English is as clean as American white bread.

But now when you go home your Spanish is brittle and you struggle for the words. You sit at the table with your loved ones and the conversation moves past you faster than you can hold on. You go to the market and your accent names you. People take you for American, and you’ve worked so hard to be one that you never thought you would want to reject the label, but no, you want to say, no that’s not quite right. It’s both. And they nod and they smile, but they have questions too. They want to know things about your home. They want you to tell them how to say things in English. You, the lacuna, you have the bittersweet privilege of unlocking the mysteries of America.

Your bisabuela was also a woman of two worlds. A Yaqui woman from Sonora who moved to Yucatán where she worked in the fields swinging her machete and cutting her hands on the henequen. Her husband, your bisabuelo, was a handsome man who read books and knew many things but died in the Revolution and your bisabuela never remarried. Whenever his name was mentioned, she said if she had been a soldadera by his side, he would have made it out alive.

When you were little, everything she had she gave to you. She forced food onto your plate and gifts she could not afford into your hands. When she was near the end, with nothing left to give, she gave you imaginary gifts and described them in luminary detail, placing air so delicately into your palms, as if it might break.

One night, years after you had moved to America, your mother was sitting at the kitchen table looking at some important papers that had come in the mail. She was very sad, so you walked over and handed her a tiny ball of air and explained that it was a beautiful flower that only she could smell. She smiled. You told her this was a way of showing love that bisabuela has taught you. Then she cried.

All of this, of course, is just my imagination of a person I will never meet. The little girl between two worlds struggling to be at home in each. This is my made-up glimpse into a life and a culture that I will never intimately know and that will never be translated to me because the people are not here and their lives, like gifts of air, can only be known by the ones who held them.

When I read the story in the paper, I imagined the struggles and triumphs and loved ones. Thirteen Americans, eight Mexicans, a German. Were the Americans only Americans, I wondered? Were the Mexicans only Mexicans? Were any of them both? I read through the names and ages. Twenty-three dead. One was fifteen. Twenty-two wounded, including a two-year-old and nine-year-old.

Never mind the terrorist’s name. But you should know he was a white nationalist who walked into a Walmart in El Paso in 2019 and opened fire. It was the deadliest attack on Latinos in modern American history. You should know he used a WASR-10 rifle, a semi-automatic variation of the AK-47, which he had legally bought online along with 1,000 rounds of hollow-point ammo. You should know he gave himself up and that he told police about a manifesto he had posted online.

Never mind the manifesto’s name. But you should know it cites as inspiration the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand that killed 51 people earlier that year, and the racist great replacement theory, and that it talks about a “Hispanic invasion” and asks readers not to blame then-President Donald Trump, whose rhetoric the author was obviously echoing when he referred to Latino migrants as an “invasion.”

Trump later used the massacre to criticize extremism on the far-left, saying he condemned “white supremacy, whether it’s any other kind of supremacy, whether it’s antifa.” In other words, there are very bad people on both sides.

Walmart stopped selling ammo for handguns and assault rifles in the United States and the terrorist was sentenced to 90 consecutive life sentences and is now pending trial that may result in the death penalty.

The thing about the lacuna is, it’s a myth that words are untranslatable. If you ask a linguist, they will tell you all those articles are kinda silly. Any word can be translated. It takes time to find the way and understand the proper connotations, but eventually the intercultural connection is made and both worlds are richer for it. But when people are taken from us, this tether is cut and this lacuna so central to the American experience, this possibility of intersecting worlds and the invisible gift it gives us, it is a loss of untranslatable sorrow that cannot be put into the words of any language.

I think about this tragedy every year and the people and families of El Paso. I hope from now on, you will too.

Andre Anchondo, 23

Jordan Anchondo, 24

Arturo Benavides, 60

Leonardo Campos, 41

Angie Englisbee, 86

Maria Flores, 77

Raul Flores, 77

Guillermo “Memo” Garcia, 36

Jorge Calvillo García, 61

Adolfo Cerros Hernández, 68

Alexander Gerhard Hoffman, 66

David Johnson, 63

Luis Alfonzo Juarez, 90

Maria Eugenia Legarreta Rothe, 58

Maribel (Campos) Loya, 56

Ivan Filiberto Manzano, 46

Elsa Mendoza Marquez, 57

Gloria Irma Márquez, 61

Margie Reckard, 63

Sara Esther Regalado Moriel, 66

Javier Rodriguez, 15

Teresa Sanchez, 82

Juan Velazquez, 77

Thank you for writing this story. I love you for telling it. It was moving for me, for very personal reasons. God bless you.