Trump Isn't Fascist. He's Progressive.

How Trump's second term echoes 19th-century politics

Alexander von Sternberg is a historian and researcher, the host of the podcast History Impossible, and a former guest on The Radicalist who came on the show to explain the Nazi roots of Palestinianism and to discuss velvet jihad, or Islam’s soft imperialism.

If there was a moment in which it became clear that an apt historical analogy could be made regarding President Trump in his second term, it was at his inauguration speech on January 20, when he said:

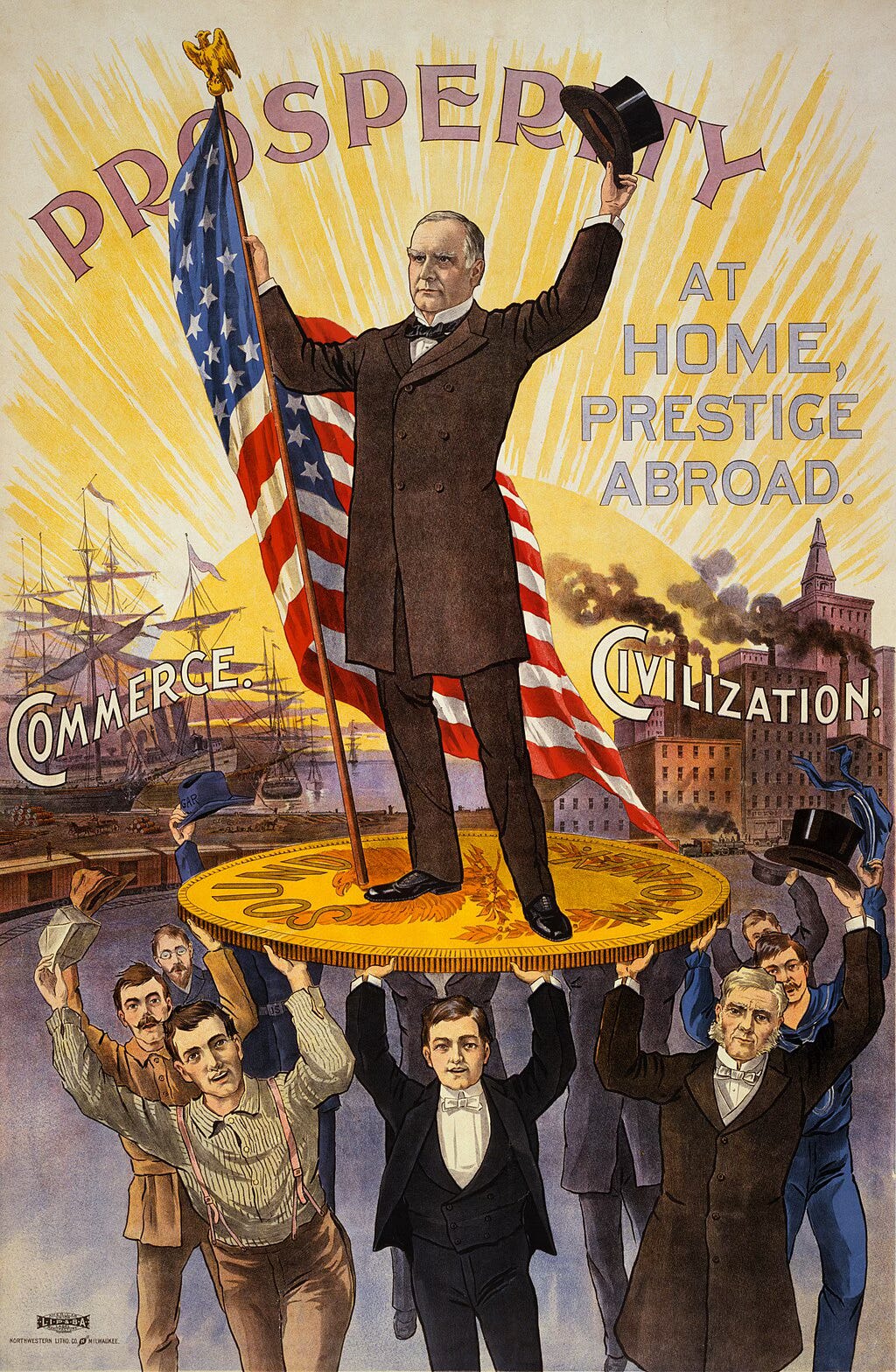

We are going to be changing the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America. And we will restore the name of a great president, William McKinley, to Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.

President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent — he was a natural businessman — and gave Teddy Roosevelt the money for many of the great things he did, including the Panama Canal, which has foolishly been given to the country of Panama after the United States — I mean, think of this — spent more money than ever spent on a project before and lost 38,000 lives in the building of the Panama Canal.

We have been treated very badly from this foolish gift that should have never been made, and Panama’s promise to us has been broken.

The rechristening of Mount McKinley, plus praise of its namesake as well as his successor, does not align with the usual comparisons made between Trump and certain historical figures. These comparisons range from the absurd and hyperbolic — Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco — to the reasonable, such as Andrew Jackson, as Eli Lake explained on his show Breaking History.

In 2016, Niall Ferguson made a compelling case for defining Trump not just in terms of populism, but in terms of the populist backlash that was occurring at the time of his first election, comparing him — as I have on my podcast History Impossible — to the Irish-American populist firebrand Denis Kearney of the 1870s.

But with the hand-over of power from Biden to Trump and the new administration’s ever-sharpening ideology, things have changed.

We now see in Trump’s second term a very different shape than the crude populism that has defined his political life for the past decade. The populist rhetoric is still there, and Elon Musk’s antics as the scheming, foreign-born royal advisor seem to be rooted in a quasi-libertarian milieu loosely borrowed from Argentina’s Javier Milei, though with less consistency — or principle.

But these are still early days, making it hard to draw firm conclusions, however Trump’s increasingly imperialist rhetoric, combined with the manic expansion of executive privilege, suggests a clear if unstated goal. Namely, having the courts and legislature ultimately sort out these power struggles while the executive branch steams ahead with its plans.

In short, Trump increasingly resembles a 19th-century progressive.

The picture that emerges is not a universally rosy one for those who understand the history of American progressivism, which is why it’s worth examining that history through a comparative lens, if only to help place Trump within the proper context of American history.

One of the most jarring things about Trump’s second term has been the interest he has shown in territorial expansion. He has pushed to retain American control over the Panama Canal, and has even attempted to insert the U.S. into Greenland’s push for independence from Denmark, essentially seeking to annex the territory.

In addition, there has been much brash talk about annexing the entirety of Canada and making it into the “51st state,” never mind that Canada is more than willing to defend itself. Perhaps most disturbingly, Trump has floated the idea of essentially turning the ruins of the urban micro-state into a slice of American-led commercialism.

Much of this has all been met with disbelief, laughter, and ridicule, including from yours truly. But there is something deeply serious behind these plans and threats. With the possible exception of Gaza — which is not being treated with the same seriousness as the other examples — these strategies are all part of a broader effort to strengthen U.S. strategic influence, particularly over the Western Hemisphere.

The Democrats were more than willing to try to appropriate the symbols and rhetoric of their populists — the One Percent, #BlackLivesMatter, #metoo — without ever really changing anything, while the Republicans under Trump seek to actually remake the American image.

All the talk involving the Panama Canal is under the pretext of securing it against control by Chinese investments, which are certainly significant with Chinese ports straddling both ends of the Canal itself. Whether or not those ports constitute a threat to U.S. national security, as Trump has claimed, is another debate. But what is clear is that securing the Panama Canal, perhaps even by force, would place one of the most important trade routes in the Western Hemisphere firmly under U.S. control.

In the case of Greenland, Trump’s remark during his address to a joint session of Congress that the U.S. would acquire it “one way or another” takes on new significance in light of the independence gradualist party’s recent victory in the country. This move has essentially made it more of a free agent, and thus ripe for the taking. But its true significance lies in Greenland’s vital strategic importance for the North Atlantic, given that 80% of Greenland lies within the Arctic Circle and acts as a defensive hub for vital shipping lanes.

Additionally, Greenland is home to abundant rare-earth minerals that are crucial for modern technology, such as smartphones and green energy batteries. Despite the people of Greenland showing little interest in joining the U.S. and instead opting for true independence, the world’s largest island would be a boon for any nation seeking to control it.

Finally, when it comes to Canada, this plan, on the face of it, is the most outlandish and nakedly expansionist of them all. However, beyond sheer imperialism, there are other justifications being floated. According to Trump, one major motivation is to curb the $200 billion the U.S. pays Canada annually. Furthermore, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has acknowledged that the Trump administration is “very aware” of Canada’s natural resources and has expressed interest in controlling them.

The talk surrounding border security in the context of fentanyl trafficking and illegal immigration cannot be discounted either, though tariffs seem to be the methodology the administration is taking in that regard. The point being, obtaining a vast territory like Canada with its innumerable resources would essentially cut out the middleman, despite the existence of NAFTA until 2020. But no one has ever accused Trump of being economically rational.

All this amounts to something very familiar to those who have studied American history during the Progressive Era, when the nation was busy developing and strengthening a sphere of influence.

A note on terminology: It may be difficult for some to appreciate this similarity because “progressivism” has long been associated with those on the left side of the political ledger. However, the progressive vision in the U.S. has hardly been unified except in terms of core principles. The differences have largely stemmed from ancillary political concerns — the George W. Bush administration was defined by Evangelical Christianity, whereas the Obama administration leaned into technocratic expertise. This ideological split has deep historical roots that first manifest in 1912 between Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt, with poor William Howard Taft caught in the middle.

After that election, the country generally embraced the more academic and genteel Wilsonian vision, leaving the bellicose and nationalist Rooseveltian brand of progressivism behind — until now. The second Trump administration has very clearly aligned itself with the legacy of Roosevelt but also, as Trump himself made clear in his inauguration speech, with that of President McKinley.

Other commentators have made similar observations. Writing for UnHerd, Michael Lind argues that Trump is governing “in a tradition of realist presidents, going back to Theodore Roosevelt more than a century ago, who have viewed world politics as a great-power club, rather than an arena for idealism.” Lind’s overall point about moral consistency is certainly debatable, but he is not alone in recognizing this shift. In The American Conservative, Ted Snider argues that Trump’s hero-worship of McKinley and Roosevelt represents something unpleasant to imagine because, as the article’s subheading points out, “his heroes were warmongers.” Clearly, Trump’s attempt to rebrand himself within this historical lineage has not been well-received by those with anti-imperialist perspectives.

This concern is for good reason. Very few U.S. presidents have been more imperialist than the progressives who ruled between 1896 and 1920. Under McKinley alone, the U.S. acquired Hawaii, Guam, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines as part of the famously lopsided Spanish-American War of 1898 — to say nothing of U.S. involvement in the Boxer Rebellion in China, the first global war of the 20th century. McKinley justified these acquisitions under “the law of belligerent right over conquered territory.”

The Philippine-American War of 1899-1902 was the most infamous of these conflicts. It erupted when Spain ceded control of the Philippines and the U.S. quickly annexed the islands instead of granting independence. Over 4,200 American soldiers and more than 20,000 Filipino combatants perished.

The justifications for the Philippine annexation were legion, ranging from strategic concerns to outright racism, with some arguing that Filipinos were not fit to govern themselves or that they were not sufficiently Christianized. But ultimately, it was about expanding the American sphere of influence, which at the dawn of the 20th century paled in comparison to the empires of Europe.

This imperial impulse was shared by McKinley’s vice resident and successor, Theodore Roosevelt, who further expanded U.S. interventionism after McKinley was assassinated when thePolish-born anarchist Leon Czolgosz shot him in the stomach.

Roosevelt’s “big stick” diplomacy, which has clearly influenced the 47th president, involved creating what became the Panama Canal Zone after taking it from Colombia in 1901, reasserting control over Cuba despite its 1902 independence, and turning the U.S. into the “police power” of the Caribbean with the 1904 “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. The Corollary justified U.S. intervention in Latin America by arguing that “chronic wrongdoing may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation.” This doctrine laid the foundation for further military occupations, such as the U.S. Marine intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1905. It also set the stage for the next major progressive president, Woodrow Wilson, to continue to expand American interventionism.

If there was one overused bromide of the past eight years, it was the invocation of fascism in almost any and all negative commentary directed at Trump.

Wilson’s imperialism has often been downplayed compared to that of McKinley and Roosevelt, likely thanks to the progressive split described earlier, as well as Wilson’s greater association with the First World War breaking out just over a year and a half after he took office in 1913. However, Wilson was no stranger to foreign intervention and occupation, particularly in Latin America, where Roosevelt’s Corollary provided broad justification for it.

During his presidency, Wilson’s so-called “Banana Wars” raged south of the border with interventions in Mexico, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Panama. Justification for American involvement in Latin America and the Caribbean aligned with Wilson’s views on the importance of “Pan-Americanism,” which he believed would create a “progressive order” that would prevent “uncontrollable chaos,” in the words of historian Lloyd E. Ambrosius.

As with Roosevelt’s own expansionist actions, there were high-minded justifications, but it is clear that this had to do with securing the U.S. sphere of interest. As historian Ivan Musicant has written, Roosevelt’s motives lay largely in “cement[ing] America’s newfound role as quadraspheric constable,” in which “the United States could militarily and unilaterally intervene in any regional state where the political, economic, or social conditions invited a European protective response in force.” Or, as Roosevelt himself said in a speech delivered in Cincinnati in 1909:

Expansion is not only the handmaid of greatness, but, above all, it is the handmaid of peace. Every expansion of a civilized power is a conquest for peace. It means not only the extension of American influence and power, it means the extension of liberty and order, and the bringing nearer by gigantic strides of the day when peace shall come to the whole earth.

This belief, that American expansionism was a force for stability and global order, provided the intellectual foundation for U.S. interventions throughout the early 20th century, driving American foreign policy and reinforcing the Rooseveltian approach to empire-building even as Wilson styled himself as a more idealistic and principled leader.

The parallels between Trump and 19th-century progressive presidents are striking, to say the least. However, the closer one looks, the more obvious it becomes that not everything aligns perfectly between them. This, of course, has more to do with the fact that the world — and especially the U.S. — has significantly changed in the last 125 years. While the second Trump administration seems animated by the Rooseveltian progressive spirit when it comes to geopolitics, this has not always been the case. Trump’s first term was animated by an energy of crude nativist populism that largely rejected global expansionism.

After all, this was the only Republican nominee in 2015 that broke ranks and denounced the Iraq War, despite falsely claiming to have always been against it. However, the road to this seeming about-face reveals not a contradiction so much as a logical conclusion.

Woodrow Wilson, despite resuscitating and maintaining the tradition of McKinley and Roosevelt’s militarism in Latin America and the Caribbean, often spoke in idealistic terms, especially in 1917 when he pled for Congressional approval to send American men into the fray of the First World War under the pretense of “making the world safe for democracy.” This was certainly sincere on Wilson’s part, driven by his messianic complex. Unlike Wilson, McKinley and Roosevelt were more in line with what is today known as Realism, concerning themselves with largely deterministic, supposedly rational interpretations of geopolitical forces that must be harnessed, rather than defied.

Similar to McKinley and Roosevelt, Trump sees the projection of American power not in terms of the Wilsonian notion of spreading American values — as figures like Bush Jr., Obama, and Biden believed — but in terms of securing interests and influence. This is a function of the worldview that has crystallized particularly, but by no means exclusively, on the American right during the last 15 years, neatly aligning with MAGA populism.

In 2011, CNN commentator and writer Fareed Zakaria released the second edition of his landmark 2008 book, The Post-American World, updated to reflect the tumultuous events that were occurring as the first edition was being published. At the time of its original writing, Barack Obama had yet to be elected into office, the War in Iraq had not yet ended, and most crucially, the consequences of the financial crisis of 2007-2009, aka the Great Recession, had not yet made themselves apparent. By 2011, Zakaria’s updated analysis of a world characterized by “the rise of the rest” was even more prescient. The War on Terror and the Great Recession made clear to many that the American way had been built on a house of cards.

But as Zakaria explains in his book, people were starting to suspect that “America had had its day” years before the financial crisis. As the co-founder of Intel, Andy Grove, said in 2005:

America is in danger of following Europe down the tubes. And the worst part is that nobody knows it. They’re all in denial, patting themselves on the back as the Titanic heads straight for the iceberg full speed ahead.

For the rest of the world, American decline became apparent even earlier. As Zakaria notes, U.S. global influence “reached its apogee with Iraq,” an unprovoked invasion launched despite widespread international opposition.

The skepticism of the American-led “end of history” that supposedly began in 1989 quickly became global. As Zakaria explains, that new world order that George H.W. Bush spoke of in 1991 quickly unwound when the unpopular Iraq War became even more unpopular as it became obvious that, despite the ousting of the genocidal Baathist regime under Saddam Hussein, the whole enterprise was an unmitigated disaster.

America, in its brief window of true global dominion, had blew its wad. However, the most striking insight provided by Zakaria is not that the Iraq War “killed American dominance” or the unipolar world order, but that it and the 2008 financial crisis accelerated preexisting global trends — mainly, the rise of the rest and thus the necessary declension of the United States. As Zakaria writes:

The unipolar order of the last two decades is waning not because of Iraq, but because of the broader diffusion of power across the world.

Chinese strategists had long recognized this transition, characterizing the world as made up of “many powers and one superpower.” But this was no benign observation. It was a strategic assertion.

It was only a matter of time before Americans themselves would begin to experience real and significant self-doubt that mirrored the doubt being felt by the rest of the world. But unlike the rising rest, who naturally saw opportunity, Americans were inevitably going to react with variations of despair.

This manifested in myriad ways in the early 2010s, most dramatically with the now-infamous Occupy Movement in 2011-2012, which ended up mostly coding left. The right had the Tea Party moment starting from 2010, but it was not clear that the populist backlash was in full swing for them until it became embodied by Donald Trump’s rise in 2015.

This first incarnation of Trump was much more inwardly focused than the second one appears to be. This was largely thanks to the influence of nativist-minded figures like Steve Bannon, but it was of a piece with the current incarnation as well, in that MAGA ideology — what little of it can actually be articulated — is firmly rooted in the idea that the U.S. is not the unipolar powerhouse it once was. The only seemingly real serious ideological figure in the administration, Vice President JD Vance, has made this clear: that the U.S. exists and should thus act like it exists in a multi-polar world.

What should concern us is expansionist authoritarianism, however it defines itself—progressivism, fascism, communism, Trumpism.

While notions of a multi-polar world are interesting for their connections to esoteric Russian figures like Aleksandr Dugin, the reality of a multi-polar world — and it is a reality — is what matters for understanding the second Trump administration’s positioning of the U.S. in 19th century progressive terms. This is because, despite how unpleasant, thuggish, and downright mean-spirited it has all been, the administration is at least appearing to be trying to make the U.S. exist in the world as it is, rather than the world as we would like it to be.

While I would argue there are multiple ways to navigate this other than the way the administration has been going about it, which I see as a deep pessimism masquerading as realism, they are taking a supposedly proven approach by mirroring the imperial, spheres-of-influence methodology of the McKinley and Roosevelt administrations 125 years ago. The primary difference between the two parties in Washington has been revealed. The Democrats were more than willing to try to appropriate the symbols and rhetoric of their populists — the One Percent, #BlackLivesMatter, #metoo — without ever really changing anything, while the Republicans under Trump seek to actually remake the American image. The last time such a thing actually happened during (relative) peacetime was indeed under McKinley and Roosevelt.

I believe therefore that it is fair, at least as of this writing, to characterize the second Trump administration as the newest incarnation of American Progressivism. What that actually means is what should concern us.

If there was one overused bromide of the past eight years, it was the invocation of fascism in almost any and all negative commentary directed at Trump. Everyone from random commenters on Reddit to Rachel Maddow took a swing at the reductio ad Hitlerum fallacy. While it is clear that this was almost certainly political theater and hardly sincere, especially given the fact that the party that saw fit to continually make fascism comparisons was apparently more than happy to hand over power to a supposed fascist, plenty of people took it seriously, and you will find no shortage of angry citizens comparing the current administration to fascism or even Nazism.

This has always read and usually continues to read as a textbook definition of a moral panic or mass hysteria. And yet there does seem to be something a little more apt about such a comparison this time around.

Of course, there is a bit of cheekiness to be expected when saying something like this. It is not to say that the second Trump administration is absolutely, resolutely, a fascist administration. That is not true. After all, the majority of this essay is elaborating on how this administration resembles 19th-century progressivism more than anything else. But the truth is, 19th-century progressivism and fascism — along with communism — are quite comfortable bedfellows. These three were the ideologies of the future 150 years ago or so, and while they all had different ideas about the specifics, they shared one thing in common: top-down authoritarianism.

Around this time in Western history, notions of government by the people were facing a lot of skepticism. There were multiple reasons for this, and they would take us far too long to chronicle. The short version is that the early-to-mid-19th century saw incredible disruptions to what had long been the relative status quo in politics, economics, and war — ranging from the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic Wars to the Second Industrial Revolution, the Year of Revolutions (1848), and the American Civil War. In short, the will of the people became associated with chaos, and generally speaking, those in power abhor chaos. This is certainly a crude and shortened version of 19th-century history, but it generally helps explain why governments, including democratic ones, would develop warm feelings toward authoritarianism as the 20th century began to loom.

These warm feelings would manifest in different ways depending on the country in question. As we know, for Germany it would become National Socialism, for Italy it would become fascism, and for Russia it would become communism. But for America, some decades earlier, it would become muscular technocratic progressivism, which endured until the 1920s, before revitalizing itself under the auspices of Roosevelt in the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression.

If one zooms in, the different ideologies of these powers cast very different shadows. But zoomed out, they all indeed share an authoritarian nature. Whether it was the Roosevelt administration forcing the slaughter of over 30,000 pigs to exert control over the livestock economy, one of Stalin’s Five Year Plans, or Hitler’s autocratic drive to make Germany self-sufficient, the essence was always the same, if not the effect.

The different authoritarian powers often looked at each other admiringly for their efforts to protect their people from the horrors of the Great Depression, and this included progressives seeing something to like across the Atlantic. They saw themselves as part of a kindred movement that had essentially grown out of the shackles of parliamentary democracies or constitutional republics; a movement of pragmatists, a movement that wanted to get things done; to “get action,” as Teddy Roosevelt liked to say.

While the Depression had given this worldview in the world’s democracies a new lease on life, these notions of top-down, technocratic, authoritarian managers taking hold of national (or civilizational) destiny long pre-dated these events. The writer and world famous progressive H.G. Wells had been, by his own account, advocating for such a shift for three decades, when he spoke on the subject of fascism in the early 1930s. Indeed, he saw the parallels between the fascist movements of Europe and the progressive movement of the early 20th century — particularly under the auspices of FDR — and he saw them in a favorable light. In 1932, he addressed the Young Liberals at Oxford, proclaiming the following:

I have never been able to escape altogether from its relentless logic. We have seen the Fascisti in Italy and a number of Franklin Roosevelt’s Fascist New Deal clumsy imitations elsewhere, and we have seen the Russian Communist Party coming into existence to reinforce this idea. I am asking for a Liberal Fascisti, for enlightened Nazis … And do not let me leave you in the slightest doubt as to the scope and ambition of what I am putting before you.

These new organizations are not merely organizations for the spread of defined opinions ... the days of that sort of amateurism are over — they are organizations to replace the dilatory indecisiveness of [democracy]. The world is sick of parliamentary politics ... The Fascist Party, to the best of its ability, is Italy now. The Communist Party, to the best of its ability, is Russia.

Obviously the Fascists of Liberalism must carry out a parallel ambition on a still vaster scale ... They must begin as a disciplined sect, but they must end as the sustaining organization of a reconstituted mankind.

H.G. Wells was not a fascist in the same way as Hitler or even Mussolini were. As Philip Coupland explained in his paper on the subject, “Wells showed how ‘fascist’ — that is elitist, authoritarian, and violent — means, could yield ‘liberal’ ends.” Fascism was, in essence, a tool to be wielded for the common good. This notion only changed after it became unfashionable (for obvious reasons) to advocate for such a tool when world events revealed why.

As Jonah Goldberg has explained, fascism only really started to get a truly bad rap after World War II began, and especially after it ended. As Goldberg emphasizes, the real reason fascism got so tarred with a broad brush was its association with the Holocaust, and for good reason. The Holocaust was, in essence, the end result of an authoritarian state with zero checks and balances and creative bureaucratic apparatus, all fueled by a singular, lethal obsession.

If you enjoy seeing tyranny exercised on white nationalists or Hamas-supporting college students, then you don’t hate tyranny; what you enjoy is the selective application of tyranny.

Fascism did not necessarily lead to the Holocaust — as seen by the relatively “favorable” treatment the Jews of Italy experienced until the Nazis took over in 1943 after Mussolini’s fall — but the Holocaust could not have happened without fascism. This is the seeming chicken-and-egg problem that tends to trip most people up who don’t study this part of history. Fascism was not bad at the time solely because of the Holocaust. Rather, the Holocaust revealed just how bad fascism could be.

I depart from Goldberg’s analysis pretty sharply in the sense that, unlike him (at least when he wrote his book back in 2007), I don’t really care whether or not fascism is the domain of the left or the right — it’s a top-down authoritarian ideology that, historically, tends to result in expansionist violence — and in the case of the Nazis, a drive for virulent race purification — and that, in and of itself, is bad enough for anyone who appreciates individual freedom and agency.

The problem is that the domains of the left and right both equally believe that if either secures power, they will lose the freedom and agency they have. Whether or not one side can make a better case than the other matters far less than the possibility (I personally believe near certainty, but one’s mileage may vary) that they are both correct, but hate each other more than they hate any kind of tyranny. If you enjoy seeing tyranny exercised on white nationalists or Hamas-supporting college students, then you don’t hate tyranny; what you enjoy is the selective application of tyranny.

This is all to say that fascism is not what should concern us. What should concern us is expansionist authoritarianism, however it defines itself—progressivism, fascism, communism, Trumpism. And, if we are to take the second Trump administration at face value with how it has been conducting itself, particularly with foreign policy (including aggressive tariffs), it is concerning. However, unlike the previously warned dangers of Trump and his movement, I do not believe it makes any sense to treat things as existential to our government.

I have heard it said that it would behoove us not to react to Trump 2.0 like a resistance — or hashtag-resistance — but rather, react to it like an opposition. Because, to be frank, that is what a democracy does. That is what a republic does. Despite the resurgence of Democratic-dominated progressivism in the 1930s that arguably continued nearly uninterrupted into the Obama era, the Rooseveltian brand lost its influence outside of the mythological context. By the 1920s, more liberty-minded administrations prevailed and, had it not been for the Great Depression providing the incentive for revisiting top-down authoritarian measures, likely would have continued, if only for a time.

The world today might be multipolar, and the U.S. needs to start acting like it understands this fact. But doing so by breathing new life into a century-old playbook of discredited, nakedly cynical imperialism is not the answer.

Thank you very much for the historical clarity.

I do not see Trump as an imperialist. I believe that he, as a successful creator, throws out wild ideas as a way of discovering opportunities. I think this is often something that entrepreneurs do as a way to move forward or make discoveries.

I believe that Trump's wild texts and wild statements are a way to set people off-balance. This allows him the upper hand in negotiations. A bit of fear helps, too.

A recent example: His idea to develop Gaza which would entail moving the people out. It sounded so wild and removed from reality at the time. But it got the ball rolling. It forced the Arab states to react. The Arab states have never, prior to this, done anything of substance about the problem of Gaza. Not only did they finally act, but the world got to see how inept they are.

I am glad that we have a President who makes things happen. Weak, wrong directed diplomacy has been ineffective, and in my opinion, destructive. Trump is performative and strategic in his "wild" ideas.

I see his "imperialistic" behaviors as the opening the door to deals. I hadn't thought of tariffs as imperialist. Trump is using them as door openers, though not all want to engage to make deals. Why wouldn't we want more level playing fields? Especially if the world is now multipolar?