They raped me beside my brother's corpse

On the history and legal realities of wartime rape

The following essay is adapted and expanded from a thread originally published on X.

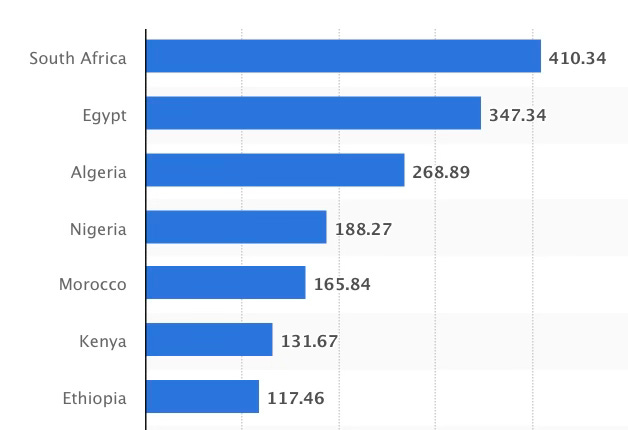

Today, I want to write about wartime rape in two of the greatest ongoing wars in the world: Ukraine and Ethiopia. You may be thinking, Ethiopia? Ukraine has the direct involvement of a major power, risk of nuclear conflict, global economic impact, echoes of World War II, and is in Europe. Why Ethiopia? Simply put, it’s the death toll. Here are the deadliest ongoing armed conflicts, ranked by total deaths:

Sudanese conflicts: 1.4 million

Russo-Ukrainian conflict: 1 million

Ethiopian civil war: 500,000

Maghreb insurgency: 460,000

Arab-Israeli conflict: 300,000

Myanmar conflicts: 200,000

But these are long-running conflicts with many chapters. The Arab-Israeli conflict didn’t start on October 7, 2023, but in 1948 with Israel’s founding. The three African conflicts are newer. The oldest, the Maghreb insurgency, began in 2002. Today, we’re in the Tigrayan genocide phase of Ethiopia’s civil war and the Israeli-Hamas phase of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Point being, the scale of human suffering should always be one of the primary factors in determining which conflicts get our attention, and by that metric, Ethiopia should be in the news a lot more often than it is. Not to mention, this is Africa’s second-largest nation and seventh-largest economy.

Now, wartime rape. The first thing you'll notice if you go looking is the sheer horror. In Ukraine, for example, you have Russian soldiers raping Ukrainian women in front of their own children. And Russian soldiers raping Ukrainian children in front of their own mothers. And Russian soldiers raping Ukrainian infants.

But the second thing you'll notice is how differently wartime rape is treated in Ukraine versus Ethiopia. Namely, the different levels of attention they get. This difference not just in terms of public awareness, but courtroom justice too. And this difference has a history.

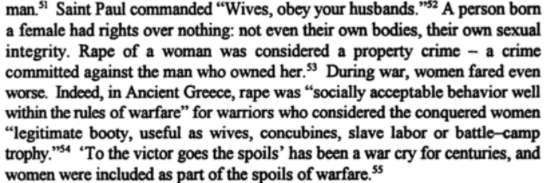

Wartime rape was historically fair game. The ancient Greeks not only thought it acceptable, but a legitimate reason for war itself. As Kelly Dawn Askin writes in her 1997 book War Crimes Against Women, it was only illegal as a property crime against the man who owned the woman.

The next major chapter in the history of wartime rape starts in 989 at the Council of Charroux. Never let people tell you the Catholic Church has not been a force of good in the world, because this is the year the Church proclaimed the Pax Dei. This was followed by the Council of Toulouges in 1027, where the Church proclaimed the Treuga Dei. The two were known together as the Pax et treuge dei, or the Peace and Truce of God, a Church movement designed to limit violence in Europe using the threat of spiritual sanctions.

It outlined when, how, and who you could fight. And it worked. The rhetoric of the Pax et treuga movement was entered into chivalric pledges. Knights vowed not to harm the unarmed, steal livestock, burn homes unless a knight was inside—or attack ladies, their maids, widows, and nuns. So the Church helped form the founding principles of chivalry, which meant knights were guided by a code that prohibited harming innocents, especially women. The trope of knights protecting damsels in distress is cliche. We roll our eyes. But it’s also part of a tradition of opposing wartime rape.

The Peace and truce movement pops up again in the modern era when the Spanish-Puerto Rican cellist Pablo Casals gave his famous speech before the UN General Assembly, “I am a Catalan,” in which he praised Catalonia and the Peace and truce movement as “the first parliament.”

Catalonia has had the first parliament, much before England … Catalonia had the beginning of the United Nations … peace in the world and against, against, against war, the inhumanity and brutality of war. This was Catalonia.

Catalonia, which did not want to be part of Spain, reminds me of Ukrainians and Tigrayans who do not wish to be part of Russia or Ethiopia, who like Casals, stand for peace. For him, this stand for peace, “This was Catalonia.” Today, this is Ukraine. This is Tigray.

The next important chapter in this history centers around the Dutch humanist Hugo Grotius, the father of the law of nations, who wrote On the Law of War and Peace in 1625, the foundational work of international law, in which he said rape “should not go unpunished in war any more than in peace.”

Nice words, but international law did not follow suit. When the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions were drawn up in 1949, they did not prohibit rape. One wonders if the absence of a woman at these conventions was a factor. Nor did the Nuremberg Tribunals charge any Nazi war criminals with rape, despite witness testimony. But the Tokyo Trial did convict Japanese officers over the Rape of Nanking, prosecuting the rape of over 20,000 women as war crimes. As we will see, racism was a factor here.

Another major moment in the recent history of wartime rape was the rape of Berlin, which saw women from “8 to 80” raped, over 100,000 total in the city, over 2 million nationwide, by up to 12 Russian soldiers at a time. Other incidents that must not be forgotten are the rape of up to 200,000 Korean “comfort women” by the Imperial Japanese Army, the rape of Peruvian women by government soldiers and members of the Shining Path, and about 5,000 Kuwaiti women by Iraqis troops during the 1990 Gulf War.

Then there is the landmark Akayesu case, the trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu, mayor of Taba, Rwanda, in which the court held that the systemic rape of 250,000-500,000 Tutsi women during the 1994 Rwandan genocide constituted genocidal rape. This was a landmark case because now, by international law, systemic rape could be prosecuted as genocide. It then became categorized as a crime against humanity after 20,000 Muslim women in Bosnia-Herzegovina were systemically raped by Bosnian Serbs in 1992. In response to these conflicts, the Yugoslav and Rwandan tribunals were created. But they had very different levels of success. And it’s important to understand why. The Yugoslav tribunal consistently focused on rape and saw more success at prosecuting it.

But the Rwanda tribunal did not focus as consistently on wartime rape, and the results were predictably poorer. Specifically, the Yugoslav tribunal has made 23 convictions while the Rwanda tribunal has only seen five that were not overturned on appeal. Even the landmark Akayesu case did not include rape at first, and only did so after public pressure five months into the trial. So what caused the disparity? This is key, because understanding this can help us better address events in Ukraine and Tigray.

The excellent study, Mobilizing the Will to Prosecute: Crimes of Rape at the Yugoslav and Rwandan Tribunals, cites three causes for the difference: funding, administrative issues, and international advocacy/media attention. Let’s consider each in turn.

First, funding. In its early years, the Yugoslav tribunal received almost double the funding of the Rwandan tribunal and spent about $75 million compared to $42 million. Second, administrative issues. The Rwanda tribunal suffered from mismanagement, incomplete and unreliable financial records, payroll problems, under-qualified staff and weak witness protection. In other words, rank corruption and incompetence. Finally, transnational advocacy and media attention. This means NGOs, advocacy groups, and media networks using informational politics, symbolism, framing, accountability politics and other methods to promote action. But once again, it was uneven.

These networks were much better at supporting Bosnian Muslim women than Rwandan women. In March 1993, International Women’s Day, the Women’s Action Coalition and Women’s Coalition against Ethnic Cleansing organized a march in Los Angeles. There were other protests too, letter-writing campaigns and, crucially, conferences to pressure the Yugoslav tribunal to focus on rape. These worked. But there were never networks of this scale or power when it came to Rwanda, and the networks that did exist did not pressure the Rwandan tribunal to focus on rape until two years after its creation.

Or consider this statistic. From April 1992, when the mass rapes began in Yugoslavia, until Sept 1993, six months after tribunal was formed, there were 139 news reports in major publications with the word “rape” in the headline. But there were only eight—EIGHT—reports on Rwanda with “rape” in the headline from April 1994, when the conflict began, until September 1995, 11 months after the tribunal was formed. And ALL these looked at rape through the lens of children born as a result.

In A Problem from Hell, the former U.S. envoy to the UN Samantha Power offers a simple explanation—apathy—writing that, in 1994, an officer of the U.S. Defense Department’s African Affairs Bureau was told by his boss, “If something happens in Rwanda-Burundi, we don’t care. Take it off the list.”

But also, Yugoslav feminists and NGO workers were far better connected while Rwandan organizations simply did not have contacts with U.S. senators, or the ear of U.S. reporters, or celebrities, or famous athletes. And sadly, in our age, this work is almost a kind of popularity contest and these networks are vital. Also key was the symbolism, with the media repeatedly tying Bosnia to World War II and Nazi Germany, a tactic that predictably sent shivers down readers’ spines. How could this be happening AGAIN in Europe? But when it came to Rwanda, well, wasn’t Africa always in the middle of some war anyway?

The point is, attention saves lives. Administrative issues are hard to fix fast, but media attention and NGO work can get the right people involved, improve funding, direct tribunals, and win prosecutorial results. That’s the power of storytelling. That said, let me end with a story from Tigray. The Ethiopian government and Eritrea have encircled Tigray, committed massacres, and are using famine as a weapon of war. There are also reports of genocidal rape. One video shows a surgeon in Adigrat hospital removing long nails and pieces of plastic from the vagina of one woman after she was raped and tortured. She said:

The soldiers shot my brother in the head and took turns raping me. They raped me beside the corpse of my brother.

Another woman was raped by a group of 100 soldiers. When she returned from the hospital with post-exposure HIV drugs, they were waiting. “Why the hell did you want this? We want you to be sick. That is what we are here for. We are here to make you HIV-positive.”