The Last Train to Utopia

A brief history of communism, Ghiblified

In the 2028 film The Last Train to Utopia ( ユートピア行き最終列車 Yūtopia-yuki Saishū Ressha), Miyazaki Hayao tells the story of communism.

They say it began with a spark, like an ember in the firebox of a mighty locomotive, and once the engine roared to life, it never stopped even when the tracks ran red.

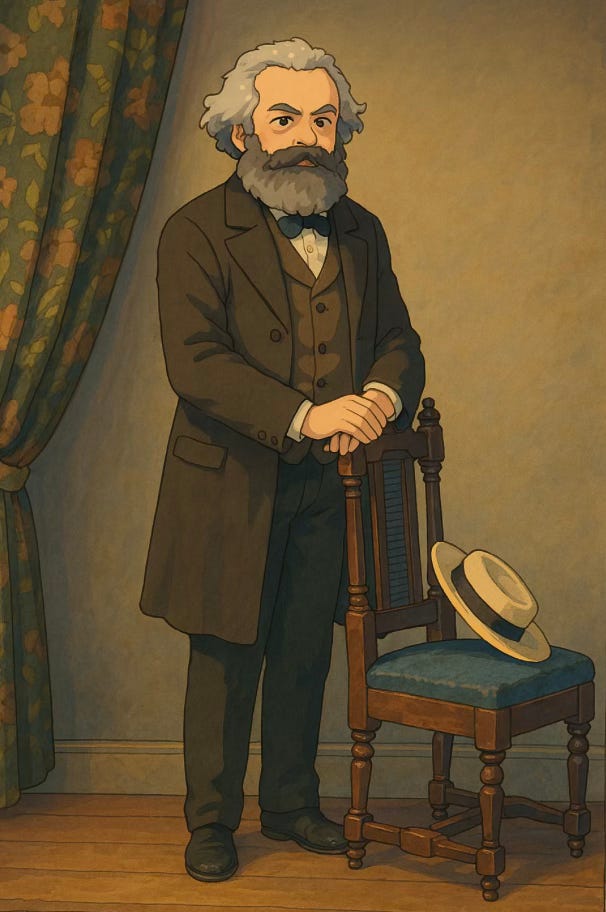

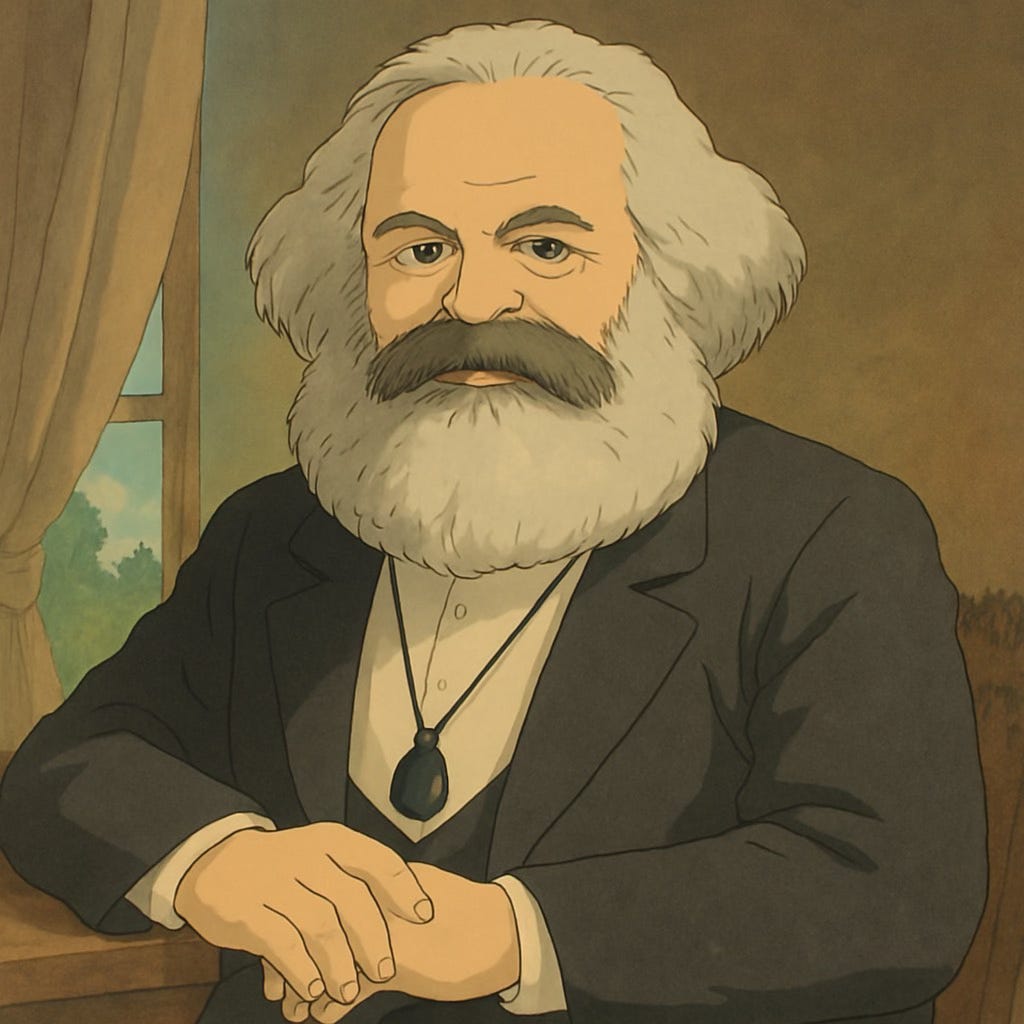

That spark was the Communist Manifesto, written in 1848 by two German journalists named Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the Father of Communism.

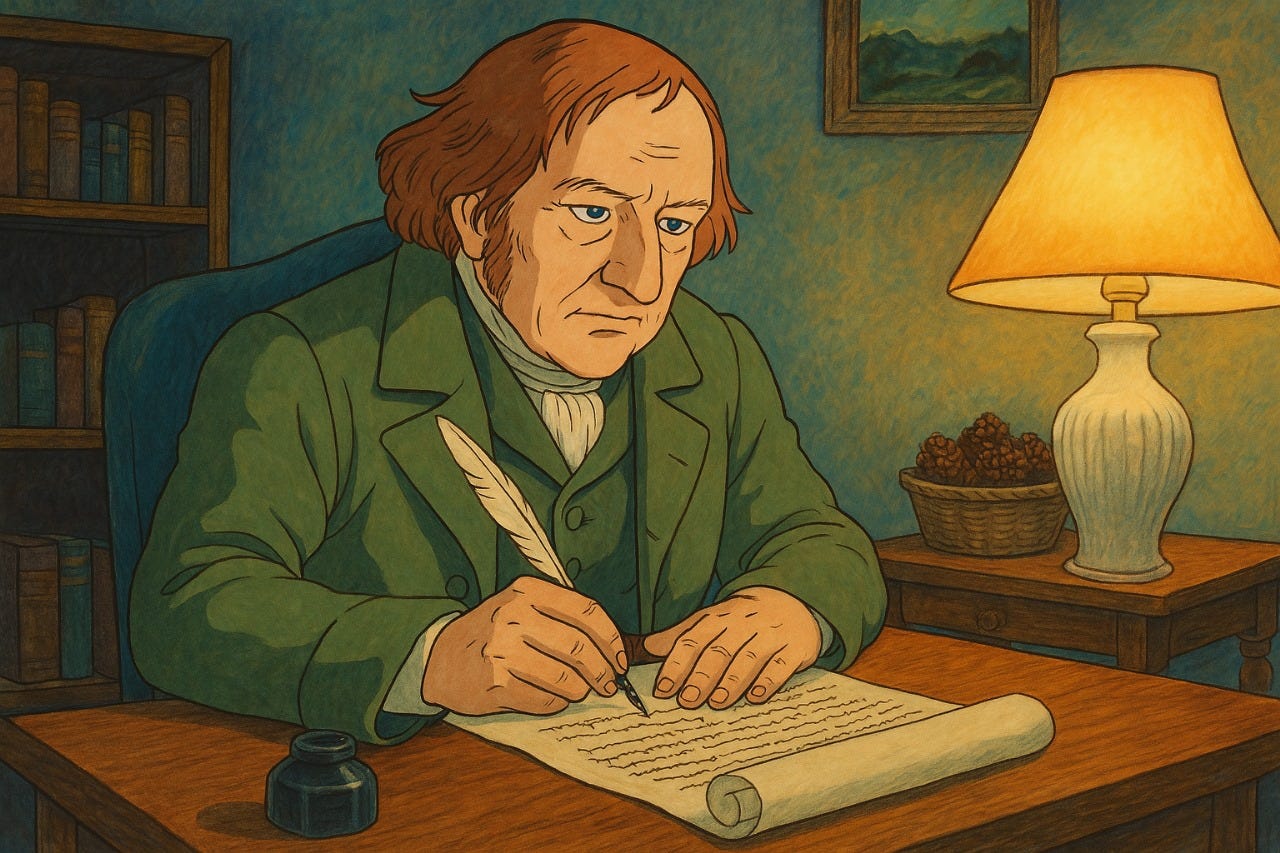

This is the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who believed humanity is moving toward universal freedom through a kind of ideological evolution in which ideas are born, opposed, and then the two sides merge to form something better.

Hegel had lived through the French Revolution and saw the Ancien Régime monarchy — under which freedom belonged to the privileged and the social order was based not on reason but tradition — violently rejected in the name of freedom and rationality, and this not only inspired Hegel to believe that the development of consciousness, or phenomenology of spirit (the title of his magnum opus) moved toward freedom through a series of back-and-forth negotiations he called the dialectic.

Hegel had also seen the tide turn once more, as Napoleon brought back autocracy by crowning himself emperor and cracking down on dissent with censorship and secret police, though at the same time, not everything was reversed — Napoleon promoted soldiers based on ability rather than birth, which had been a revolutionary demand, and retained property rights, and more.

After Hegel died, his ideas swept Europe and a young Marx embraced his ideas while studying at the University of Berlin, though he later turned the dialectic on its head by arguing not that ideological evolution drove the physical realities of history, but that its physical realities — or material conditions — drove the evolution of ideas.

It was the material conditions of the Industrial Revolution, in which factory workers were horribly exploited in London, where Marx lived, that produced the idea of communism, in which Marx argued that the reason the workers were paid so little despite doing all the hard work was because they didn’t own the factory or the machines inside it — but that they had the true power, and could simply rise up.

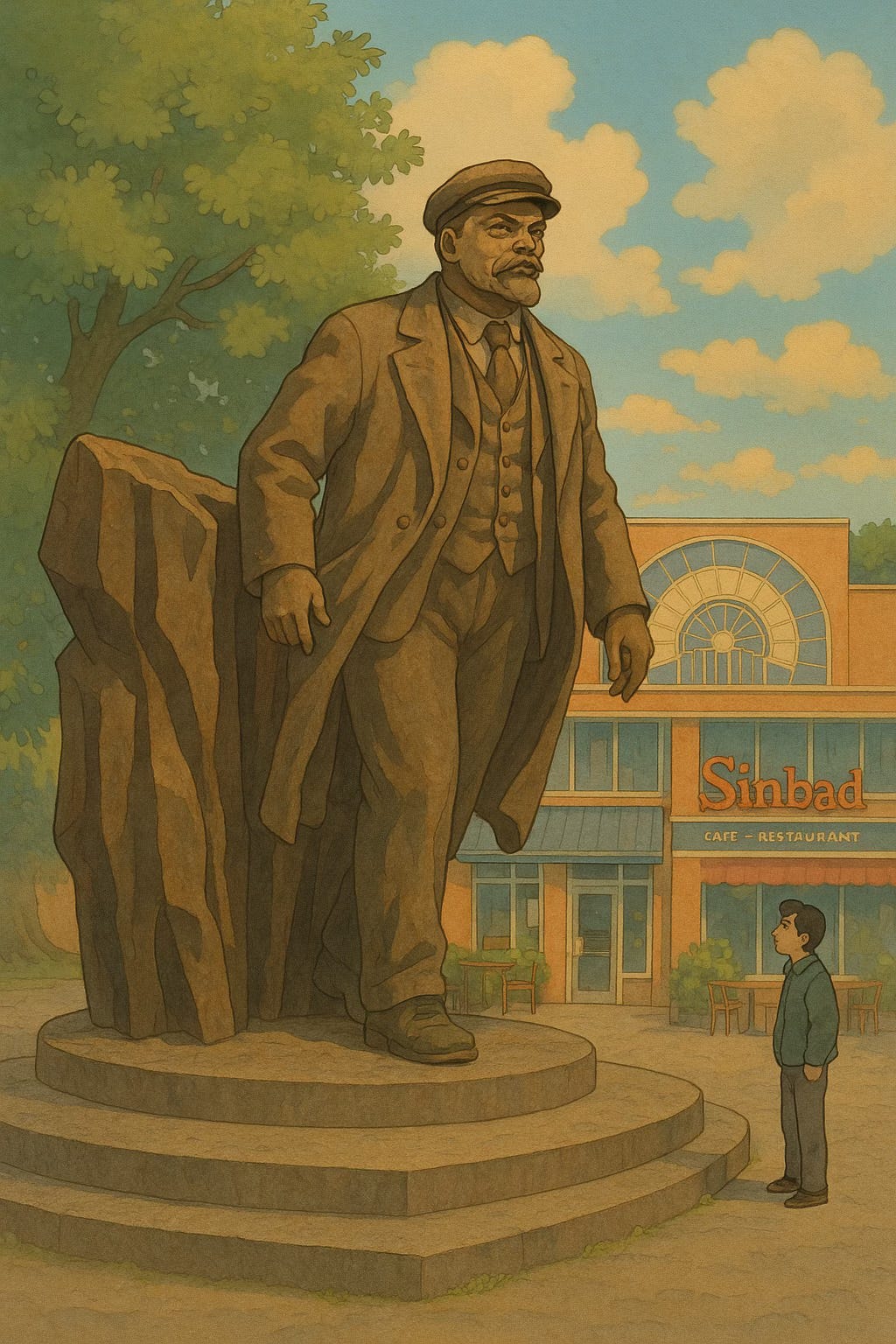

Vladimir Lenin used this idea to weaponize the power of the people against the Russian emperor, turning it into a revolutionary battle cry infused with the promise of liberation.

And it worked — Lenin and his Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace and took control of the country, and the people of Russia soon got their first taste of Lenin’s promise, in the form of food shortages and bread lines and famine.

In order to make sure the starving population remained loyal, the new Soviet government policed them relentlessly, crushing any whisper of dissent, grabbing people off the streets and from their homes, questioning them for days, until they were so out of their minds with exhaustion they were willing to confess to anything.

And if they did confess, the gulags awaited them, which were brutal labor camps where about 18 million people were sent to be worked to death.

Stalin’s nightmarish purges not only eradicated dissidents, but even erased them from the history books, making it as if they had never existed in the first place.

Life became so unbearable under the new Soviet dictatorship that when World War II broke out, some even felt a glimmer of hope that this would finally bring change, but in many ways things only got worse.

And before you knew it, the cancer had spread to Asia — up to 45 million people died from famine during the Great Leap Forward, including up to 20 million children.

The Chinese had their moment of hope too, but it was snuffed out in the Tiananmen massacre where roughly 3,000 people, many of them students, were slaughtered.

And as in Russia, once again dissidents of any kind were shamed and beaten, grabbed from their homes and questioned, and in many cases, much worse.

And from there it spread to Korea…

And Cambodia…

And many other parts of the world…

And in many different forms…

And though people in some countries finally rose up and ended the reign of terror…

In others, they remain defeated to this day.

And in others, they are at risk of defeat.

If you enjoyed this, you may also enjoy my essay on the art of Soviet children’s books.

Ghiblified fun for everyone.

New word and style for me: Ghiblified! Great way to tell this history.