The Eternally Resentful Young

How every generation becomes the villain of the next

President Donald Trump’s Liberation Day on April 2 set off a full-scale tariff war that sent global markets into an immediate and brutal free fall. Within days, untold amounts of wealth evaporated, international goodwill toward the United States crumbled, and trade ties snapped. Trump eventually hit pause, dialing tariffs back to 10% on all countries but reportedly increasing tariffs on many goods from China to a punishing 145%. Now the future looks uncertain. The geopolitical consequences remain volatile. Putting that aside, we are seeing a sort of rhetorical rebirth online in response — the rhetoric of generational resentment.

Generational resentment between Millennials — and increasingly Zoomers — and the supposed villainy of Baby Boomers is nothing new in recent history. But it reached a new, unexpected crescendo in the week that followed Trump’s tariff-palooza, one that became encapsulated in a pretty powerful exchange between two influential figures on X. One was Tim Wise, whose bio reads, “Critical Race Theorist. Yes. That’s the thing you don’t understand.” The other was Anna Slatz, whose bio reads, “overlord @reduxxmag,” as she is the co-founder of the gender critical MAGA-radfem rag Reduxx. To be clear, if it wasn’t obvious enough, I find neither of these people particularly compelling, interesting, or even sane thanks to their intellectual bona fides. Regardless, I found their exchange compelling — even harrowing — in its representativeness that turned out to be far greater in scope than even the Boomer v. Millennial discourse that I honestly thought was largely dead by the end of the 2010s.

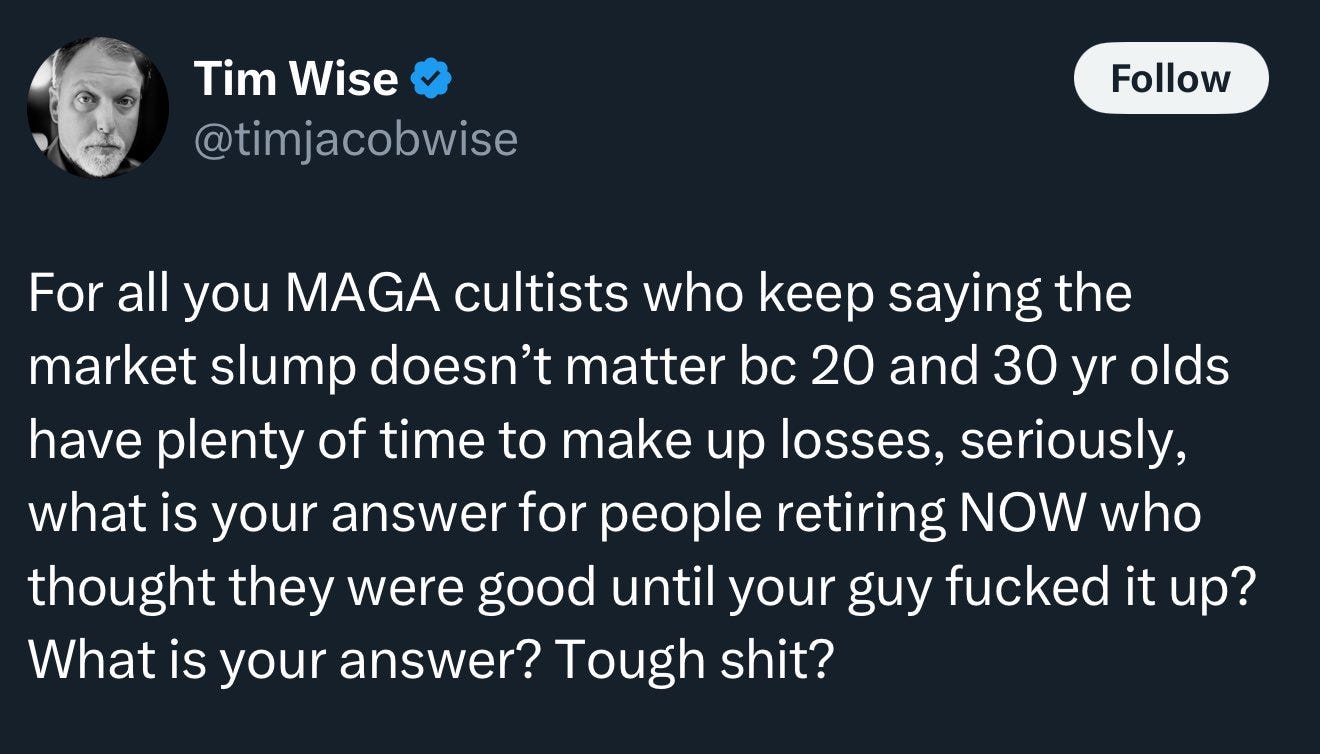

Wise opened with the following:

To which Slatz replied:

The conflicted emotions I experienced reading this exchange were intense. Because on the one hand, I did sympathize with Slatz’s spittle-flecked, righteous rant. It is very hard for most Millennials — especially those of us who graduated from our undergraduate schools in the late 2000s — not to sympathize with the idea that the futures we were convinced to invest in were a bouquet of naïve wish-casting at best, or a pack of outright lies at worst.

But, in the end, I thought Thomas Chatterton Williams put it best when he replied to Slatz, “Nothing positive can come out of such unbridled resentment.” Because that really was the takeaway. Less that Wise had a point — though he certainly does, and one hard for me not to sympathize with thanks to having Boomer parents — but more that the rage being expressed by Slatz is largely performative. The rage — and thus, the nihilistic worldview behind it — was the point. As another person noted, “You do realize that ‘I've endured some hardship so now I want EVERYONE to endure it’ is a child’s worldview, right?”

However, within a few minutes of reading this whole exchange and stewing in the feelings it brought up in me — a technically broke grad student, mind you — I realized this really is just the newest incarnation of something that has happened before, more than once.

We saw Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and other American writers of the post-WWI era express the profound disconnection between the generations through their work. The constant theme was not just disaffection, but profound betrayal.

My now-natural response to such things is, of course, to examine and then share what kind of ties this may have to history, and sure enough, it has plenty. Because not only is generational resentment between Boomers and Millennials/Zoomers nothing new — again, see the majority of the 2010s — but generational resentment is nothing new in general. And we can go back much further than the Boomers’ resentment of the Greatest Generation to see that this has always been the case. In fact, we will completely eschew that generational fight from this analysis, because it is such well-worn territory for anyone who has ever watched an Oliver Stone film. Our periodization for this trend will begin in the 1920s.

Many people have heard of the “Lost Generation” thanks to the incredible artists — mostly writers — who emerged as part of it. But we forget why they were considered “lost” at our peril, if we are to believe that the resentments some Millennials and Zoomers are experiencing against Boomers is somehow unique. The Lost Generation was scarred by the worst war ever fought up to that point in Western history, and this certainly colored their resentments as they emerged in the aftermath of World War I. Young soldiers returned from the trenches deeply disillusioned with the older generation that had sent them to war. These young men felt fundamentally betrayed by the patriotic rhetoric and nationalist ideals promoted by their elders, a process powerfully depicted in the incredible 2022 remake of All Quiet on the Western Front.

And indeed, Erich Maria Remarque, the author of the original novel, portrayed young soldiers who came to see that the patriotic values instilled by parents, teachers, and authority figures were all deeply hollow in the face of the industrial-scale slaughter an entire generation had just faced.

Similarly, we saw Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and other American writers of the post-WWI era express the profound disconnection between the generations through their work. The constant theme was not just disaffection, but profound betrayal. This is because the sense of betrayal was not merely political — it represented a complete breakdown of trust in the moral authority of the older generation.

There was an overall post-war dissonance and deep psychological impact created by the so-called Great War. The dissonance experienced by the war-youth generation was particularly acute, as they felt “betrayed not just by the regime, but also by their very own selves,” to use the words of Bernd Weisrod. This psychological impact created what British historian Mary Fulbrook terms “dissonant lives,” where individuals struggled to reconcile their pre-war identities with their traumatic experiences. The shock of this betrayal transformed into a pervasive sense of shame and disillusionment, visible in the aforementioned writings and cultural expressions of the 1920s. While there certainly was no comparable trauma experienced by Millennials and Zoomers — apart from those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan — it is hard not to see a similar dissonance within people who came of age during the late 2000s and early 2010s, between what they had been taught would be their future and the crushing reality of that future.

War clearly is not a prerequisite of intergenerational resentment today, nor was it one over 100 years ago. In fact, the generation before the Lost Generation — particularly in Germany — experienced its own collective rejection of their parents’ moral values, opting instead for a more romantic view of things and serving as a future guidepost for a lot of Third Reich mystical sentimentalism. This was known as the Wandervogel (“wandering birds”) movement, which began in 1895-1896. The Wandervogel movement embodied a profound rejection of what young Germans perceived as the stifling, materialistic, and inauthentic values of their Wilhelmine parents, who were defined by the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II from 1890 to 1918. This sentiment extended beyond mere teenage rebellion — it represented a coherent critique of the entire social and moral structure created by their parents. Many participants felt their elders had constructed an artificial and constraining society that prevented authentic self-expression and true community.

Middle-class youth organized hiking trips, folk singing gatherings, and nature retreats to escape what they viewed as the corrupting influence of urban industrial society created by the older generation. Rather than simply representing a typical generational gap, this movement explicitly criticized their parents for betraying authentic German culture and natural ways of living. One can see why future Nazis might see an appeal and utility to this framing, especially given their allegedly stated aims of capturing the youth. While certainly taking on a primitivist bent and one that seemed very much defined by a hyper-nationalist sense of “German-ness,” this phenomenon of intergenerational resentment was neither confined to Germany nor to modern nationalistic sentiments.

France had its own intergenerational squabbles a century earlier, one that bled across several different generations in the nearly constant political turmoil that rocked the country during the 19th century. For over half a century, a series of French revolutions and counter-revolutions created distinct generational conflicts, with each new cohort resenting their parents’ political compromises. In the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789, the nation was thrown into chaos and violence the likes of which had never been seen in living memory, resulting ultimately in the expansionist dictatorship of Napoleon, and leaving much of France politically divided. This was reflected in the attitudes held by the generation that came of age after the revolution, who often criticized their revolutionary parents for either going too far with radical violence or not going far enough in creating true liberty.

Ultimately, these historical patterns reveal that feelings of betrayal often crystallize around moments of significant social, economic, or political transformation.

This initial split in opinion matters less than the fact that the issue was more generational than political. Napoleon’s tyrannical reign eventually unified resentments into one against the prevailing monarchical order, and by the 1830s, many young French intellectuals and activists expressed resentment that their parents’ generation had settled for this monarchy rather than delivering on the revolutionary promises of liberty, equality, and fraternity. This culminated in the 1848 Revolution, in which the younger generation who participated felt betrayed by their elders who had compromised with the previous restoration monarchies. Radicalized writers like Victor Hugo captured the sentiment that the older generation had failed to secure the freedoms they initially fought for, instead settling into comfortable bourgeois lives while abandoning revolutionary ideals.

Other examples proliferated throughout Europe in the 19th century, including the rise of the Hegelians in Germany — such as a young Karl Marx and Ludwig Feuerbach — who criticized the older generation of German philosophers for making intellectual compromises with political and religious authorities. In essence, they believed their philosophical “fathers” had betrayed philosophical principles by reconciling them with the Prussian state and Christian theology rather than following reason to its revolutionary conclusions. In addition, the English Industrial Revolution — felt via class tensions, as explored by the great labor historian E.P. Thompson — created a situation in which young apprentices and journeymen in traditional crafts often resented the way their parents’ generation handled the transition to industrial production.

Many felt their elders had failed to protect craft traditions and guild systems that had ensured quality production and stable livelihoods for centuries. Instead, they perceived their parents as having sold out to factory owners and industrialists, betraying centuries of craft knowledge and community structures. In short, while the details differed, the theme often remained the same: the previous generation(s) had, at best, failed to lay the sufficient groundwork for the promises they had allegedly made to the generation of their children and grandchildren, and at worst, selfishly hoarded the resources for themselves and destroyed any chances that these future generations would see any benefits whatsoever.

Like all historical analogies, it is important that we remember that this is not a 1:1 comparison. While the generational conflicts described above often arose from specific events like war and revolution, modern generational resentment seems to be a little more amorphous, with faceless forces such as climate change, perceptions of inequality, and mental stability vis-à-vis technological disruptions serving as the “Big Picture” challenges faced by Millennials and Zoomers. These large-scale challenges are made all the more apparent by the fact that we are more rapidly connected to one another than ever before. The discourse has become amplified by true global connectivity and data-driven comparisons of generational wealth and opportunity that were never as significantly and easily available in the 19th and 20th centuries. In that sense, we do live in unprecedented times.

However, those specific differences belie the broad similarities that carry on across time — namely that all of these challenges are perceived as existential in nature, and the idea that these crises were created and oftentimes worsened by the selfishness or moral corruption of the previous generations. Righteous anger at Boomers for “wrecking the environment” or “stealing our houses” is no different than righteous anger at the nationalists that sent a bunch of naïve boys off to war only for them to come back disfigured and traumatized for life, if they even came back at all. It is even explicitly said in Anna Slatz’s commentary: “You stole our futures, and you made the world infinitely worse for us in every way.” The difference in emotional valence and essence is nanoscopic. Generally speaking, younger generations have always perceived their elders as prioritizing short-term gains over long-term stability when disruptions occur. And throughout modern history, disruptions are the rule, never the exception. If one wants to point to the real “good old days,” they are really speaking about the medieval era, where life expectancy was so low that generations were probably less than half the length they are now.

Ultimately, these historical patterns reveal that feelings of betrayal often crystallize around moments of significant social, economic, or political transformation. These historical cases remind us that while the specific grievances may change, the dynamics of intergenerational resentment have remained remarkably consistent throughout human history. Disturbingly, what is also consistent across time, is the greater acceptance and even participation in political violence. During the late 19th century and early 20th century, for example, political assassinations became as close to the norm as any modern society could probably tolerate, ranging from the bombing of Russian Tsar Alexander II to the shooting of President William McKinley. Alexander and McKinley’s killers shared few things except two related things: their youth, and their radical politics. Nikolai Rysakov was a mere 20 years old when he threw the bomb that killed Alexander in the name of a revolutionary cause, and the anarchist Leon Czolgosz was 28 years old when he shot President McKinley in the stomach. One may not want to put too fine a point on it, but these characteristics are not unlike those possessed by the alleged assassin of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson.

So what is to be done? Many fingers are often pointed — as this essay has indeed shown — and this act of habitual finger-pointing only appears to make things worse, or at the very least keep things stuck in place. It is tempting to simply throw up one’s hands and profess hopelessness, seeing this as just another example of human nature’s faults. After all, what can explain the shared characteristics of the resentments being expressed across time, circumstance, language, and culture? To answer that question, one simply needs to look at what is and, broadly speaking, what has been shared across those divides. It appears, at least to me, to be quite simple: parents and teachers imparting the wrong lessons.

While many events that inspired its publication in 2018 have somewhat faded from memory, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s landmark book, The Coddling of the American Mind, makes one of the most compelling cases for imparting the value of resilience upon future generations in recent years, specifically by encouraging antifragility within children and adolescents as they mature. The concept of antifragility comes from Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who defined it in mathematical terms as “a convex response to a stressor or source of harm […] leading to a positive sensitivity to increase in volatility (or variability, stress, dispersion of outcomes, or uncertainty, what is grouped under the designation ‘disorder cluster’).” Haidt and Lukianoff say that this is a value that should be cultivated by “giv[ing] your children the gift of experience — the thousands of experiences they need to become resilient, autonomous adults,” which “begins with the recognition that kids need some unstructured, unsupervised time in order to learn how to judge risks for themselves and practice dealing with things like frustration, boredom, and interpersonal conflict.” This kind of mindset seems to be exactly what would protect future generations from becoming caught in the zero-sum undertow of intergenerational conflict.

Could it really be this simple? It certainly seems too easy. And it is; obviously previous generations had the freedom encouraged by Haidt and Lukianoff, and the problems of generational conflict and entitlement persisted. This is because that “hands-off” approach was never particularly conscious and rarely paired with authoritative parenting styles, in which explanations for consequences were given. Paired with authoritarian or uninvolved parenting styles, only the strongest would, in essence, survive, and those without guidance would simply become worn down. This neo-Darwinian approach to parenting has largely fallen out of favor for more permissive and the so-called “gentle parenting” styles we hear so much about, which clearly help very little in cultivating resilience, much less antifragility. This is to say nothing of the pedagogical state of the American education system, which seems to do even less in cultivating such qualities.

It is true that sometimes there are circumstances that completely rip away any sense of control from younger generations. It is true, for example, that no millennial who participated, suffered, and died in the Iraq War had any say in planning its execution; they were indeed pawns of a greater scheme devised largely by Baby Boomers. However, with the heart-wrenching exception of being killed in war, learned resilience, especially paired with reasonable guidance, is always a path forward in the face of adversity. Perhaps it is the case that other factors — both environmental and even biological — are impediments that simply cannot be overcome with this style of upbringing and education. But it is not unreasonable to suggest we try. Otherwise, the intergenerational conflicts we keep seeing will likely remain as cyclical as the seasons.

People are individuals, not groups. This "generation war" nonsense needs to stop.