The Death of the Newspaper

The newspaper industry is dying and media moguls are blaming the wrong people—everyone else.

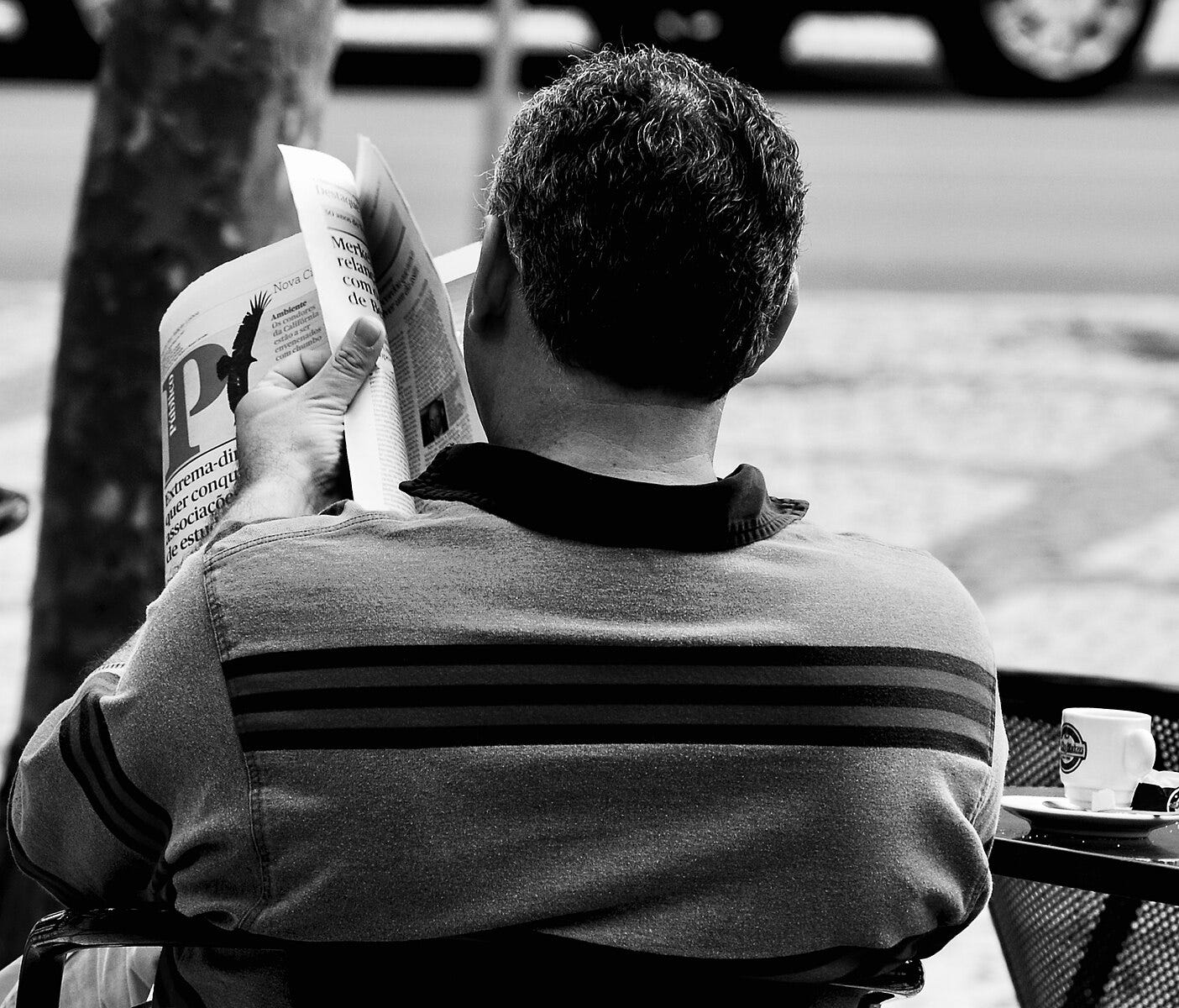

My father read several newspapers every morning, sometimes while smoking his pipe. He was an Air Force veteran, hobbyist carpenter, military boxer, and doting husband. I therefore grew up believing these were the manners of manhood and from a young age, I learned to measure and mark a board, pack a pipe, and slip a jab. I learned the love that a good man has for family and the respect he holds for the uniforms that guard you while you sleep, as Kipling put it. What’s more, I learned to love a good broadsheet. In some homes, the paraphernalia of masculinity might include a MIG welder or cherry picker. In others, maybe an old chisel plow or combine in the barn. In ours, it included a 16 oz. hammer, heavy bag and gloves, and the morning paper. But the paper was more than just the news. It was a sign of one’s desire to know the world and therefore just holding one open seemed to say something good about the nature of a man.

Or at least, that’s how I saw things as a boy. I joined the school newspaper staff when I was 11 years old. I have since turned in work for various papers around the world. I wrote my opinion for The Wall Street Journal. I was the national editor and sports editor for the sister paper of The New York Times in South Korea. I sat on the editorial board of The Seattle Times. I still enjoy the pulpy feel of newsprint, the crackle of turning pages, the classic look of serif font, the heft of the Sunday edition and the checkered layout of the page. I like the logic of news grammar, the little ritual of folding each section, the art of the headline. I love to see a grabby lede, a chewy nutgraf, and a punchy kicker. I have written style guides, designed layouts, edited stories, written stories, taken pictures for stories. The thing about a newspaper article is, it’s not an art form so much as an amalgam of art forms, from the typeface to the reporter’s voice, all working in concert to tell you what matters most in the world right now.

I suppose my love for the printed paper will never die, even if the business of making papers itself is fading away. No doubt, we are witnessing the death of the newspaper in the United States. As a former newspaper man myself, I view this with some dismay. But my dismay is over the dying of newspapers as they were, the thing my father held in his hands as he sat in a kitchen suffused with the smell of pipe tobacco and hot coffee, and that is arguably something that died long ago. What is crumbling now is not the Fourth Estate in all its edifying honor, but the propagandistic corporate instrument that has taken its place, an instrument that churns out fear porn for the political right and shame porn for the political left. So to some degree, what we are seeing is the death of something that ought to die, and my dismay is over the fact that it will not be replaced by that elegant education that came before.

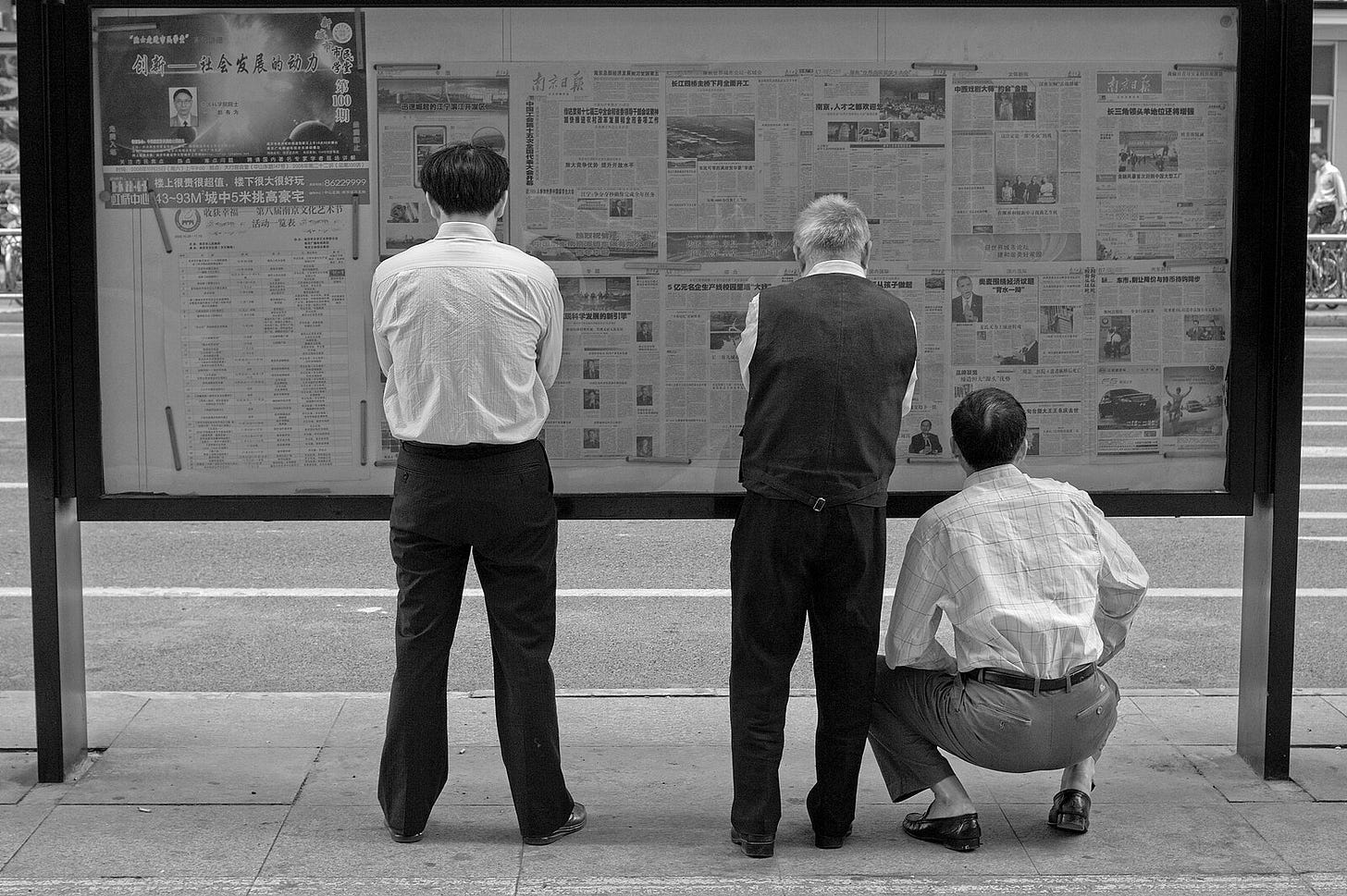

They say that the term “fourth estate” came from the godfather of political conservatism, Edmund Burke, though it was the historian Thomas Carlyle who first told the story. The British press was given access to the House of Commons for the first time in 1771, and Burke remarked that there were now four estates—clergy, nobles, commoners, and, he added, “in the Reporters Gallery yonder, there sat a fourth Estate more important far than they all.” Today we might rephrase this in terms of branches of government rather than estates, and as every school kid knows, the purpose of having separation of powers is to provide a system of checks and balances, with the fourth estate providing the greatest check of all—that of the Truth. This is why people read papers, because they offer facts and analysis as a means of conveying the truth. Or at least, that’s the idea. But just as our faith in the first two estates, the clergy and nobles, faded once we realized they cannot be trusted, so too has our faith in the fourth.

This week, the Los Angeles Times announced that it has laid off at least 115 people, or more than 20% of its newsroom. They did it via Zoom, took no questions, and gave no answers. Jared Servantez, assistant editor of breaking news at the paper, said a colleague told him, “that was like a drive-by.” The L.A. Times is the 5th largest daily in the nation after The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, and The Washington Post. This is cataclysmic, not just because of what it will do to the L.A. Times or the breadth and depth of news coverage in the City of Angels, but because of what it heralds for the newspaper industry more generally. There is a pale rider darkening the door of American newsrooms. Why is this happening? Let me explain.

The easy answer is, the circulation of daily papers is tanking hard, as shown by Pew Research data published this past November. You may be thinking, well of course, everyone now gets their news online. But I’m afraid the problem runs far deeper than that.

Unique visits to newspaper websites is also dropping like an anchor, having now hit the lowest level in a decade. What’s happening here is not merely a transition to digital media, but the death of so-called mainstream media overall, and I say “so-called” because given these trends, it’s not really mainstream anymore. It would be more accurate to talk of Big Media, corporate media, or media conglomerates.

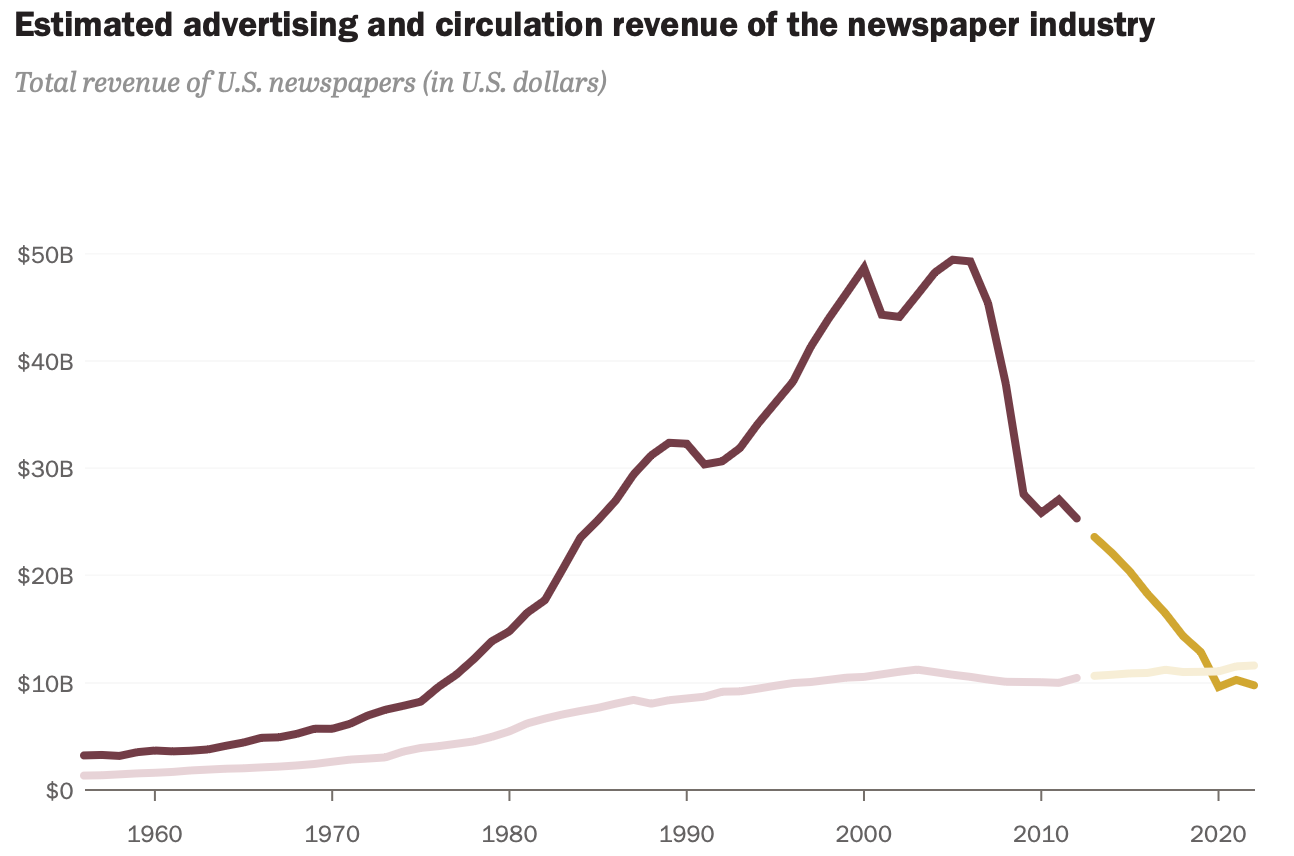

One major factor in this is the collapse of ad and circulation revenue of the newspaper industry. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau put out in June 2022, newspaper publishers took in about $22.1 billion in revenue in 2020, compared to about $50 billion just two decades prior.

“The culprits are clear,” the Hill reported in 2022. “Over the same time period, revenues generated by internet publishing and broadcasting firms and web search portals — companies like Facebook, Google and Amazon — saw advertising revenues skyrocket. More recent data from the Service Annual Survey shows advertising across those platforms more than triple, from $49.3 billion in 2013 to $160 billion in 2020.”

But this is not the whole story because let’s face it, people do not look at newspapers the way I once did as a boy. Not even I look at them that way anymore. As we did with the clergy and nobles, we have come to eye the fourth estate with great suspicion. They are up to something, we have discerned. They are not here merely to inform and make of us a better citizenry. All too often, they massage the facts. They manipulate. They lie. And we have come to understand this. In a letter to Edward Carrington, written on January 16, 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

I would love to agree with Jefferson, were that we had newspapers that were more valuable than government itself. But that is not the world we live in. Jefferson was making a point about how information and education about current events matters more than the very State itself. I agree that this is still the case, and that sunlight is the best disinfectant, but I do not believe that newspapers continue to pull the curtain back and let that sunlight in. I am not saying that they do not do this at all. I have good friends doing fantastic work at major papers. But I am saying that all too often, they also do the opposite. The only major newsroom I have worked in within the United States was that of The Seattle Times, whose publisher, Frank Blethen, wrote this in September:

Today we are facing our most serious threat yet – Google’s monopolization of digital advertising, which has destroyed newspapers’ primary source of revenue and is one of two primary reasons the U.S. is becoming a nation of news deserts … The other reason the local newspaper system is in free fall is that hedge funds and absentee financial opportunists now control the majority of what is left. Academic studies indicate that 80% of original local news is created by the local newspaper, and that local newspapers, where they still exist, are still the most trusted source of news and information.

Except The Seattle Times Company is a conglomerate that devours local news while its CEO talks about the importance of local news. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer is no more after a legal battle with Blethen’s company, which also owns the Yakima Herald-Republic and the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. In 1995, the company snapped up The Issaquah Press, Sammamish Review, SnoValley Star, and Newcastle News. The Issaquah Press was the newspaper of record for the city of Issaquah and delivered the news to 20,000 homes every week. Newcastle News was delivered for free to 5,000 homes in Newcastle. Sammamish Review was delivered free to 15,000 homes in Sammamish. SnoValley Star was delivered free to 12,400 homes in North Bend and Snoqualmie. They are gone now, devoured by a conglomerate. In 1998, the company expanded to the state of Maine with the subsidiary Blethen Maine Newspapers, and the Blethen family began snapping up local papers there too, including the state’s largest daily, the Portland Press Herald, as well as the Maine Sunday Telegram, Kennebec Journal, the Morning Sentinel, The Community Leader/Maine Switch, and The Coastal Journal. Less than 10 years later, the company decided to cut and run.

I suspect the problem was not Google, but perhaps poor managerial decisions that led to a loss of public trust. To give just two examples, in 2007, a paid ad in the Portland Press Herald announced a sermon titled “The Only Way to Destroy the Jewish Race.” Portland’s Jewish community was furious. The paper said it put new safeguards in place to prevent another such incident. But two weeks later, another paid ad depicted a Jew as banker who “takes your money in ways big and small.” This led to an investigation by the Anti-Defamation League as well as Steven Wessler, director of the Center for the Prevention of Hate Violence, and the Jewish Community Alliance. “No word when the Press Herald intends to begin serializing The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” wrote Dan Kennedy at Media Nation. Less than a year later, the Portland Press Herald was gutted in three rounds of lay offs and Blethen put it up for sale. Most of the other Maine papers were sold to private investors.

When The Seattle Times fired me after I criticized Vladimir Lenin, which you can read about in the essay Hitler and the Seattle Times, I received many messages of support expressing loss of trust in the paper’s judgment over the decision. But my story is tragic in its mediocrity, disturbing perhaps most of all because of how common stories like mine have become. Everybody knows that if you hold your breath for a fews days, the lying mob will move on. But it takes a tiny bit of courage to do so, and we have seen so many news outlets tripping over each to prove that they have no spine at all. So yes, the digital era has put papers in a bind. Google is drinking their milkshake. But it is also true Americans are turning away from conglomerate papers because they no longer trust them. In fact, American trust in mass media has been plummeting since the late 1970s, as shown by Gallup polling data published in October.

This is not solely attributable to the decline in Republican trust in the media either. Although that has fallen at a faster rate, Democrats are at their lowest level of trust in mass media since 2016, and even before that they were on a depressingly downward trajectory. Gallup concludes that “Americans’ confidence in the mass media to report the news fully, fairly and accurately is at its lowest point since 2016 … Gallup in June found confidence readings in both TV news and newspapers that were near their historical lows and last December found a record-low-tying rating of the honesty and ethics of journalists.”

This is a crisis of trust as much as it is a crisis of technology, and part of that has to do with declining trust in our institutions generally, but part of it also has to do with newspaper owners behaving in spineless and slimy ways. How much trust does a newspaper instill in its readers when it sides with unhinged communists instead of its own journalist? How many other examples can you point you of newspapers siding with a particular political fringe rather than being brave enough to defend its journalists or publish politically incorrect facts, but facts nonetheless? And what lesson does the public ultimately draw from such patterns?

When Joseph Pulitzer retired in April 1907, he gave a speech about what impact his departure would have on the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, given that he was its publisher. “I know that my retirement will make no difference in its cardinal principles,” he said, “that it will always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty.”

Newspapers today are no longer drastically independent, nor are they always devoted to the public welfare, but more often to their own. Nor do they fight with demagogues or the raging mob, but nowadays, side with them. They have become something other than they were, and while I deeply admire the good and honest work being done by serious journalists at many papers today, I myself rarely turn to them for the news. I have found better sources. Like many of you, I now follow individual reporters, think tank analysts, professors, and public intellectuals. I listen to these people through Substack, YouTube, X, or personal conversation. It takes more time to curate a list of trusted voices, but the result is better than any broadsheet. I do sometimes still check the major papers to glance over the headlines and read a story if the lede grabs my attention. But my mornings are now filled keyboard taps and cursor clicks rather than the rustling rhythm of pages being turned in time. I think we have truly lost something beautiful and great. But I also think it was run ashore by the people captaining the ship. I will always miss it, and when abroad, I always grab a physical copy and find myself a cafe. At home too, morning is still a time to read the news, and it may no longer carry the whisper of wood-pulp pages between my fingers, but morning is still a time for worldly ideas, a time that still smells like coffee and, when the mood strikes me, pipe smoke.

In the 50's we had 6 newspapers delivered to our house throughout the day. It was unthinkable that we would not be privy to what was happening in our city, state, country and the world. In 1957, at age 13, I heard Patrice Lamumba on a radio broadcast say that in the US we got only two sides of one side of the world news. I was horrified. If this were true what was I missing. As a young teenager I began to subscribe to an English version of La Monde in order to see what the rest of the world was seeing. My disillusionment has only grown over the past decades. I also seek out voices of integrity which is one reason I subscribe to your newsletter.

When you lose trust in a person because you know they lie then it is difficult to get that trust back.

It's similar for much of the mass media.

The mass media must regain our trust or they will decline even further.