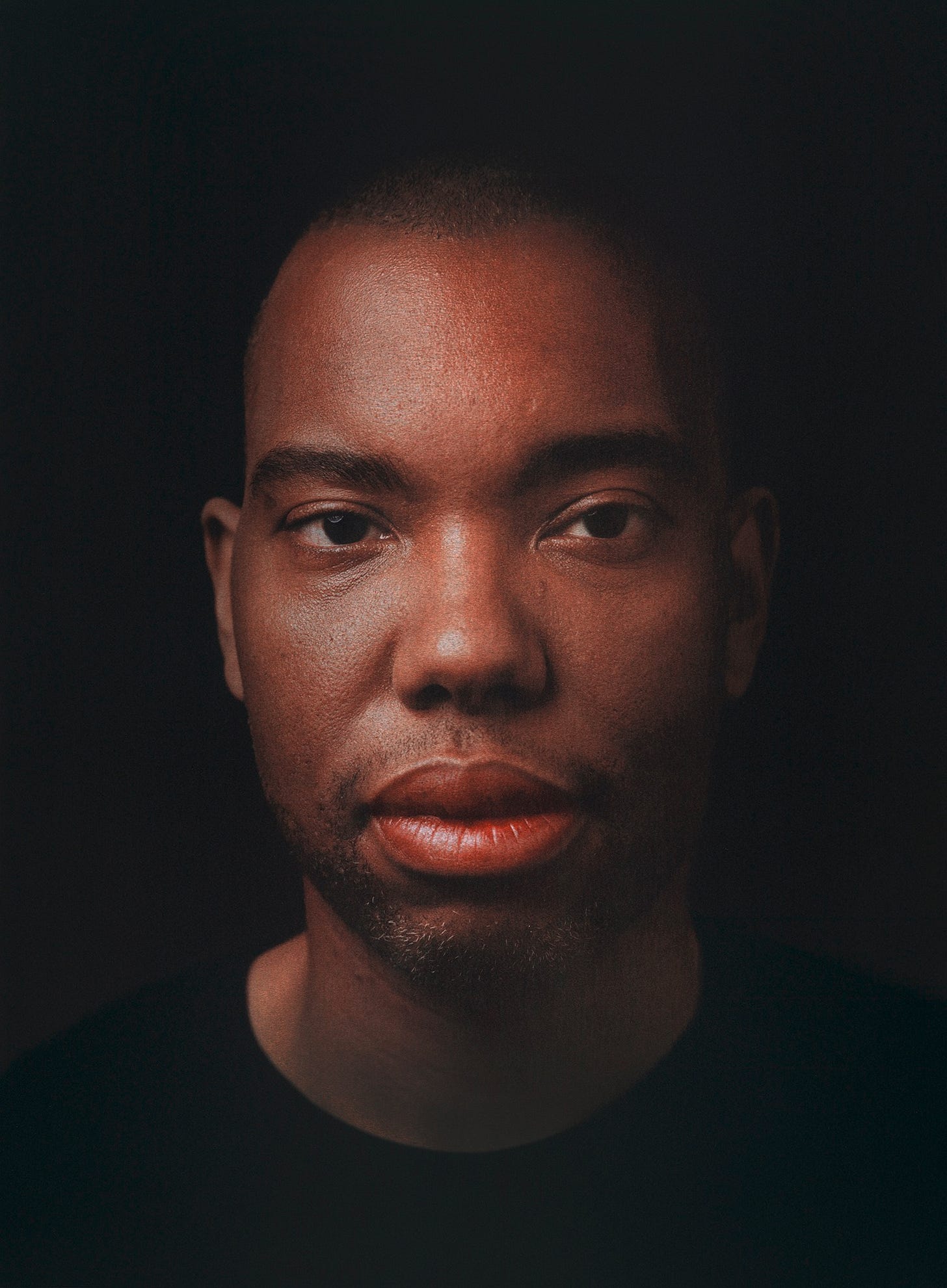

Ta-Nehisi Coates and the World as It Is

The author's new book is an Orientalist comedy

In his new book The Message, Ta-Nehisi Coates explores how storytelling can distort our understanding of the world. Ironically, he initially intended to write a book about writing itself, in the style of George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language.” I say ironically because the golden rule of writing is “show, don’t tell” and although he tells us throughout the book that our stories distort reality, the text becomes an accidental comedy when he repeatedly shows us what he means by doing it himself.

The story Coates most loves to tell, of course, is that systemic racism and white supremacy are not just historical artifacts but ongoing forces that continue to shape American society. In Between the World and Me, Coates argued that racism is embedded in the very fabric of American life and as foundational to our democracy as the Constitution.

The book ends up being one long question—what’s between the world and me?—and the answer ends up being in the only place he never looks.

The book ends up being one long question—what’s between the world and me?—and the answer ends up being in the only place he never looks. Namely, his own ego.

Still, plenty of ink has already been spilled on the matter, and I’m not here to rehash the merits of the Everything Is Racism argument, but to discuss Coates’ new book, which is a collection of four intertwined essays. Although three of the essays seem to exist mainly so that the fourth one on Israel, which is fully half the text, can be a book.

In the first, Coates imagines himself addressing his writing students at Howard University, whom he calls “comrades” and declares that, as writers, their job is “to save the world.”

In the second essay, he brings the reader along on a trip to Dakar, Senegal, where he reflects on how Africa has been portrayed in Western narratives as either a place of savagery or romanticized idealism, lacking all complexity. This lack of complexity, he suggests, is the consequence of an unacknowledged racism that wants to take authentic African experience and present it merely as a means to entertain or argue political points within white society.

Remember that point. We’ll come back to it.

Coates grapples with this Noble Savage trope and the contrast between Dakar’s vibrant contemporary culture and the Western tendency to view Africa as impoverished, or as merely some historical backdrop. His piercing intellect dissects the Western myth of Africa as devoid of any innovation or complexity.

This is a myth perpetuated by the lack of complexity presented in films such as the Leonardo DiCaprio movie Blood Diamond, a drama about the geopolitics of the diamond trade set against the backdrop of the Sierra Leone Civil War, with commentary on the morality of global consumerism and the broader implications of Western complicity in African conflicts, as well as themes of friendship, redemption, despair, and harrowing ethical dilemmas. You know, simple stuff.

According to the story Coates likes to tell, the Truth has got to be better than the facts suggest.

Or consider the genre-bending samurai horror Saloum, which is literally set in Dakar, or the Netflix hit The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, about a brilliantly innovative Malawian boy. Or The Last King of Scotland, or Hotel Rwanda, or Beasts of No Nation. And let’s not forget that in Black Panther, one of the highest-grossing films ever made, the hero’s homeland Wakanda is a backwater where the most advanced piece of technology is a hammer.

Sarcasm aside, he has a point. Namely, that Westerners do historically have an ugly habit of oversimplifying cultures. But what’s stuck in the past isn’t the West’s view of Africa, but Coates’ view of the West. It’s as if he stopped digesting any media after 1980. But it’s easy to see what’s really going on here. Dakar is predominantly black and so, according to the story Coates likes to tell, the Truth has got to be better than the facts suggest. Therefore, he corrects the record by giving us a new story, one that lacks all complexity and uses authentic African experience as a means to argue a political point to his overwhelmingly white readers.

Remember that line above?

This is why you’ll find no exploration in The Message of modern slavery in Dakar. Nor does Coates have anything to say about child labor, child abuse within Quranic schools, human trafficking, rampant sexism, or literally any of the dark complexities of modern Senegalese life that do not fit the story he wishes to tell. Because the story Coates tells is that if it’s black it’s good, and if it isn’t, that’s just some racist stuff white people made up. At one point, he almost comes face to face with his own racism, writing, “I was still afraid that the Niggerologists were right about us.”

But the epiphany never arrives. Instead, Coates brushes this mirror aside and reasserts his Afro-narcissism to smugly judge, of all things, the good people of Senegal. He has dinner with a Senegalese writer and his wife who note that their culture values lighter skin tones. You can cut Coates’ stink of superiority with a butter knife. The Senegalese ain’t woke and Coates finds their ignorance “chilling.”

After whitewashing Dakar for us, Coates is off to America where he applies his paintbrush to Columbia, South Carolina, the old capital of the Confederacy, and one of the cities where his book is banned. Here, he has some insightful reflections on the wooden nature of American mythology and the way it resists challenge or even improvement. Yet just pages away in either direction, it becomes clear that Coates has only partly taken this lesson to heart.

Finally, he visits the Middle East.

Coates spends 10 whole days in Israel and the West Bank. He speaks neither Hebrew nor Arabic. He knows nothing of Judaism nor Islam. Yet incredibly, miraculously, he comes away convinced he’s solved the world’s most complicated conflict. More than this, he says, the whole thing is “uncomplicated.” All you gotta do, he says, is take the whole thing and look at it through the lens of … wait for it … slavery in America.

Because remember, the whole book is about how we blind ourselves to reality by slapping simplistic stories onto truths we never bothered to understand.

Coates seems to want to be some kind of black American Edward Said, or at least, to operate within the tradition of Said’s legacy. So it’s worth considering how precisely he manages to do everything Said ever howled against. In his classic work Orientalism, Said criticized Western scholars for the nasty tendency of flattening the complexities of Middle Eastern politics and culture to simplistic, binary narratives that would be easily digestible for Western audiences. Coates does this by claiming the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is nothing more than a “Jim Crow regime.”

This is the trashy take given that Israel is more diverse than America and true slavery only exists on the Palestinian side.

Said also railed against the way Orientalist scholarship used selective emphasis while erasing other aspects of Middle Eastern reality. He complained that Orientalist representations often choose to include only what fits their narratives, ignoring all else in what academics these days would call an “erasure.” Here, witness Coates’ decision to weigh in on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — without mentioning Hamas, October 7, or the history of terror attacks on Israeli civilians.

One solution to Orientalism, Said argued, was to avoid simplistic binaries. But Coates bravely ignores this advice. Another solution, according to Said, is to engage multiple perspectives. Said hated that Orientalists were so arrogant as to hold forth on cultures whose people and voices it never deigned to consult. This was the hallmark of Orientalist thinking. Yet Coates has openly confessed he had no interest in engaging Israeli perspectives. Or any that contradict his narrative.

All this is like watching a boxer try to slip a punch, then trip and fall so that his face smashes directly into his opponent’s glove. It’s amazing to see, really.

And this is precisely the problem with his worldview and that of his woke assembly in reading. Coates is a storyteller, and by God, he is not going to let the facts get in the way of a good story. He is a man who has lost any capacity to step outside his own opinion and see the world as it is, and has become so convinced by his own mindset he can no longer learn anything about the world outside his skull.

It was Jonathan Haidt, I believe, who once said that a stubborn refusal to update one’s view is a colorable definition for stupidity.

I remember turning away from his blog bc it was depressing and repetitive. More, he seemed to be suffering from clinical depression. At the risk of being an armchair analyst, I believe he did undergo clinical depression… and the world rewarded him for it. So he holds tight to his worldview instead of enjoying his good fortune. The only celebrity who looks more miserable is Ellen Page

Thanks for speaking truth to idiocy.