Oppenheimer's moral genius

The new film is a much-needed lecture on ideological extremism

I just finished watching Oppenheimer and it’s a masterpiece.

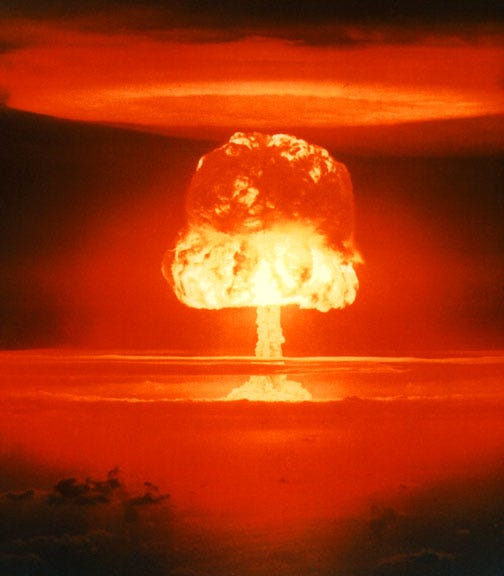

The three-hour biopic, written and directed by Christopher Nolan and based on the 2005 biography American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, stars Cillian Murphy as Julius Robert Oppenheimer—the theoretical physicist who developed the first nuclear weapon as part of the Manhattan Project.

To my surprise, communism is a major theme in the film.

Oppenheimer’s brother Frank was a member of the American Communist Party, as was his best friend, professor of French literature Haakon Chevalier, and his lover Jean Tatlock, and his wife “Kitty” Oppenheimer. These relationships are explored in the film.

Oppenheimer himself donated to a variety of humanitarian causes and that got him into trouble during the McCarthy era. For instance, he hosted fundraisers for the anti-fascist Republicans of the Spanish Civil War.

The Spanish Civil War, which lasted from 1936 to 1939, was fought between republican democracy and fascist dictatorship. The leftist Republicans comprised various socialist, communist and anarchist groups while the Nationalists were made up of fascists, monarchists and conservatives led by General Francisco Franco. The Soviets backed the Republicans while the Nazis backed Franco. The Nationalists won and Franco ruled Spain until his death in 1975.

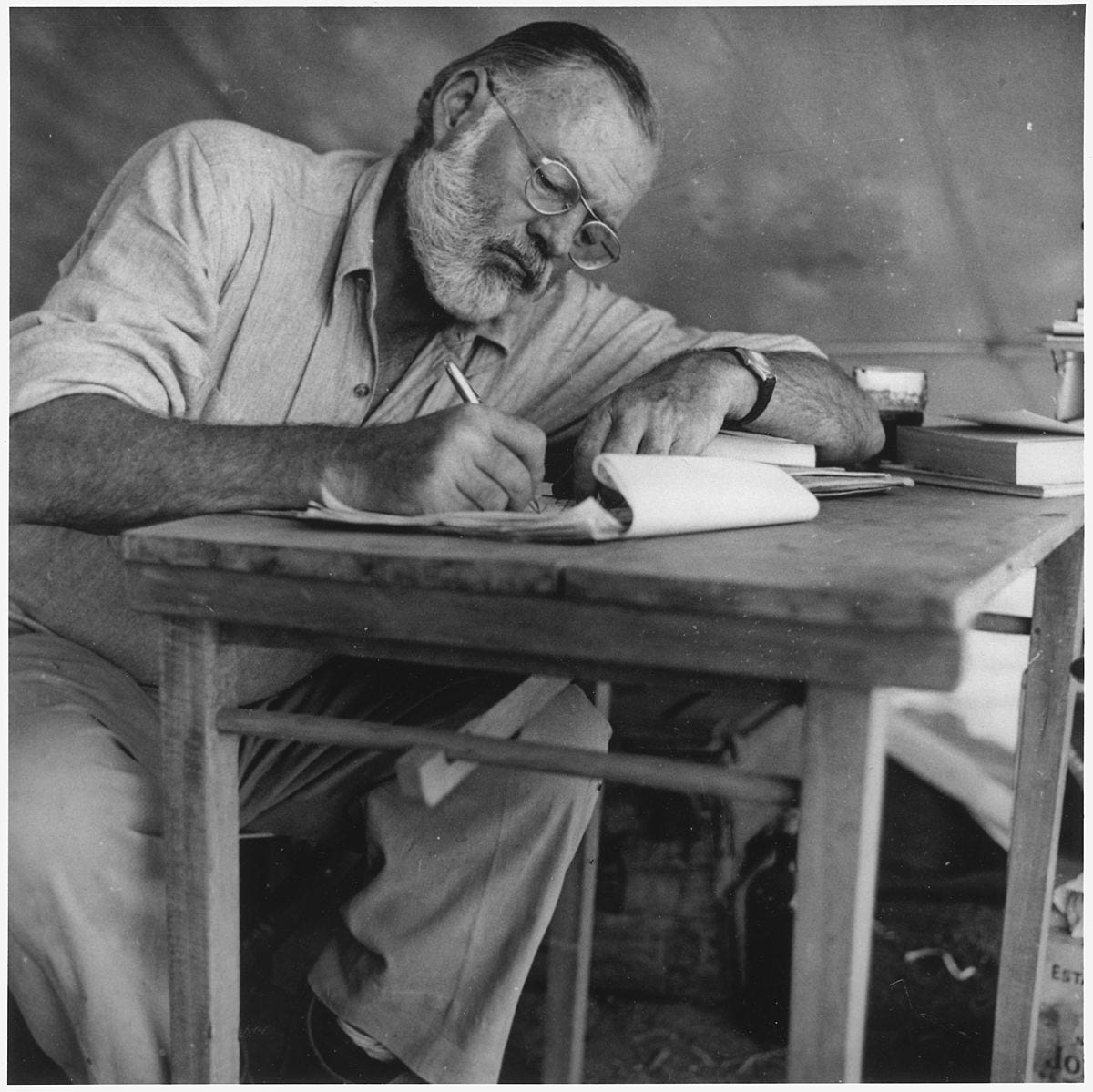

Many intellectuals at the time supported the Republicans, not because they were communists, but because they were anti-fascists. This includes Ernest Hemingway, who wrote about the war in his masterpiece For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Like Hemingway, Oppenheimer’s support for Republicans had more to do with his basic moral beliefs and opposition to Nazi Germany than support for communism itself. He gave money to Spanish refugees, for example. But he did have an intellectual interest in communism, and he subscribed to the Communist newspaper People’s World. He also, as the film depicts, took part in communist discussion groups while at Berkeley. But again, this was about worker rights and doesn’t necessarily suggest support for communism.

Nevertheless, his relationships with loved ones and the Berkeley union efforts were later used by the U.S. government to tar and feather him—long after he had offered his services to the country and helped defeat the fascistic Japanese Empire. Part of the film focuses on the 1954 security hearing in which Oppenheimer’s clearance was revoked. These scenes present the scientific genius as a profoundly loyal patriot who was stabbed in the back by mindless ideologues, and that sets up one of the main social commentaries of the film.

In an early scene, his friend Chevalier foreshadows this betrayal while speaking to Oppenheimer at a cocktail party, saying of the U.S. government, “They think socialism is a bigger threat than fascism.”

“Not for long,” says Oppenheimer. “Look what the Nazis are doing to the Jews. I send money for them to emigrate. I have to do something. My own work is so abstract.”

Oppenheimer then describes to Chevalier the manner in which stars collapse, adding that no astronomer has yet proven such theories. “Right now all I have is theory, which can’t impact people’s lives.”

He is then introduced to Jean Tatlock, who later becomes his lover, and who immediately starts talking to him about communism. She observes that, despite having read all three volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital in the original German, Oppenheimer does not appear to be committed to the cause.

“I’m committed to thinking freely about how to improve our world,” he replies. “Why limit yourself to one dogma?”

“You’re a physicist,” Tatlock snaps back. “Do you pick and choose rules? Or do you use the discipline to channel your energies into progress?”

This one scene tells us three important things about Oppenheimer. First, he wants to have a practical impact on people’s lives, hence his donations to Spanish Republican refugees as well as German Jews fleeing fascism. Hence his later work on the bomb. Second, he disdains ideological dogma. Third, he freely takes from ideologies, even taboo ideologies such as communism, whatever aspects seem righteous and effective. The unspoken answer to Tatlock’s question at the end is probably yes, he does pick and choose rules. Even in physics. There’s another scene where he’s in the classroom telling a student that light behaves as a particle and a wave. It makes no sense, he says. It can’t be true. And yet, he adds, it works.

Oppenheimer is a pragmatist. He doesn’t care what makes sense or what people deem to be true. He cares what works.

He applies this attitude to physics, weapons development and politics alike. What he admires about communism is that it presses for labor rights. It stands against fascism. So he’ll take from communism as readily as the Bhagavad Gita if it will help him “channel his energies into progress.”

In another scene, Oppenheimer is talking to Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, played by Matt Damon. Groves was the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer who headed up the construction of the Pentagon and was the director of the Manhattan Project. In this scene, Groves has come to speak to Oppenheimer about potentially joining the Manhattan team. Oppenheimer lays out a grim reality for Groves—the Germans are better at engineering and science in general.

“In a straight race,” says Oppenheimer, “the Germans win. We’ve got one hope.”

“Which is?” asks Groves.

“Antisemitism.”

“What?”

Oppenheimer explains, “Hitler called quantum physics ‘Jewish science,’ right to Einstein’s face.”

In other words, the Germans are better at science but many of the best scientists, especially the best particle physicists, are Jewish. Germany’s antisemitism might just be its undoing, Oppenheimer is saying.

People have previously commented on the fact that Nolan’s Batman films are a reflection on the post-9/11 police state, or U.S. imperialism and the War on Terror. You’ve got Batman dressed in what looks like police body armor, using surveillance tech and beating criminals beyond necessary force. You’ve got the Joker presented as a homicidal terrorist. You’ve got Bane presented as some kind of Occupy Wall Street thug. In one scene, Bane proclaims, “We take Gotham from the corrupt, the rich, the oppressors of generations who have kept you down with myths of opportunity, and we give it back to you, the people.”

These words could be the chant of Antifa rioters. And so the question is, when is violence justified? Is Batman’s extrajudicial violence okay because he’s doing it in the name of crime-fighting? Is Bane’s terroristic violence okay because he’s doing it in the name of the victims of capitalism? In Oppenheimer, Nolan suggests an answer.

The film shows us communist ideologues. They’ve got a point when it comes to labor rights and fighting fascism, but they cling too tightly to their religion. We see Tatlock become increasingly bitter, looking worse and worse in each successive scene. (In reality, she had clinical depression and tragically died by suicide in 1944.) The film shows us American ideologues too. The witch-hunting McCarthyist ones who grill Oppenheimer in the hearing. Their moral ground is no higher than that of the communists they despise. The third group of ideologues in the film, of course, are the Nazis. They are ultimately defeated, the film suggests, not because they have a less powerful military but because they are slavishly devoted to an evil ideology that costs them, among other things, some of the greatest scientific minds of a generation.

This is why I disagree with statements like the one below.

Let’s put aside the fact that, yes, Oppenheimer was Jewish. And yes, there absolutely should be a movie that centers on the Japanese experience. I’ve seen several made by Japanese directors—Barefoot Gen, Black Rain, Rhapsody in August—but am aware of no major Hollywood film that has ever done this. It’s an unforgivable blind spot in American cinematic memory and a disgrace that we can nuke a country twice and most Americans know next to nothing about it.

However, this particular film is not about the Japanese experience. It’s about ideological extremism. Whether you’re on the left or the right, whether you’re Spanish, Russian, German or American, and even if you’re fighting the good fight in the name of the persecuted, you are never so right that you can afford to be dogmatic.

This message is as important now as the conversation about police violence and U.S. imperialism was when the Batman movies came out. Our political environment has been overrun by the culture wars. In the U.S., woke excesses have reached frightening extremes while the far-right wanders deeper and deeper into the Q wilderness.

And yet both sides of the political spectrum have important values to contribute to the national conversation and our republic cannot truly thrive without them.

Oppenheimer’s scientific genius led to the bomb. But his political genius, which amounts to pragmatic cherry-picking, is maybe the only thing that leads to peace.

I didn't like this movie, and that does not mean it was a bad movie, it was great, very well done I didn't like it because I really wanted to see a different movie about Oppenheimer. Two books that cover this period 'The White Pill' and 'Stalin's War' have really put me off post WW2 hagiographies. A movie that covers this time period, after 80 years that does not address the criminal double standard that was applied to Right wing and Left Wing authoritarianism is almost anachronistic. Funny enough, the only ones that covered this point in the movie were Oppenheimer's interrogators. As much as we can understand the unfairness he endured, this is a fair point to make: 'When did you adopt a conscience about the weapons you were making?'

I think that was a fair question in the very narrow scope of determining if a person should be eligible for handling our nation's secrets.

This was not someone who merely had some idealistic beliefs about Communism, and workers rights, he was also someone whose associates had deliberately hid and excused the truths about a looming tyranny that could easily have engulphed much more of the world than it had. A few of these also delivered those secrets to the USSR. He may not have had any criminal guilt, but as a leader, he did bear significant responsibility.

To me, the real hero was Kissinger, who remained clear-headed enough to became one of the most potent fighters against Communist authoritarianism, and was vilified for it (and let's be honest, other things) for most of his life. The ideas he pushed, from Mutually Assured Destruction to The approach to China, were ultimately the most effective tools that brought down Communism (as we know it).

It's more than just "pragmatic cherry-picking". Dogma is, above all, a failure of imagination: the inability or unwillingness to imagine situations to which one's dogma is inapplicable, to imagine how someone else might see things differently, to imagine an outcome that addresses their concerns as well as one's own.

Oppenheimer was a man of great imagination. It is tragic but unsurprising that he was persecuted by people with less.