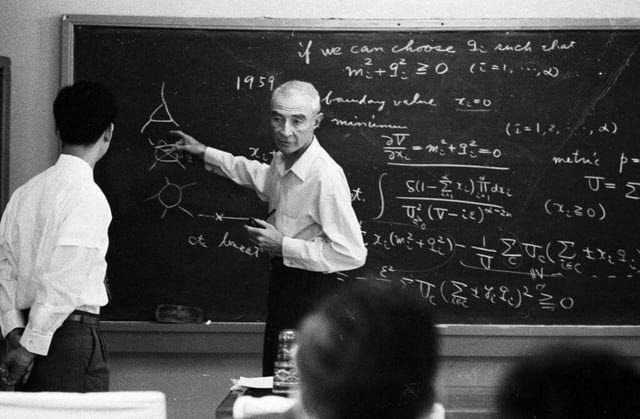

Oppenheimer's last lesson

What the father of the atomic bomb taught us about peace

Fifteen years after the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan warmly received the father of the atomic bomb for a three-week lecture tour that began in Kyoto on September 5, 1960. The tour was sponsored by the Japan Committee for Intellectual Interchange (JCII), which was founded in 1945 at the start of the U.S. occupation of Japan. Americans founded the JCII because they understood that in order to accelerate Japan’s transition to democracy, they had to instill Western political values, economic systems, and social norms. They had to Westernize Japan.

This was not democratic conditionality, which is the practice of imposing democratic principles such as free and fair elections or human rights as conditions for receiving aid or joining an international organization. Rather, this was a kind of normative democratization borne out of cultural determinism, which is the belief that one’s culture determines individual behavior, but also that it determines economic and political outcomes. The Russia historian Richard Pipes, father of the Middle East Forum head Daniel Pipes, has argued that centuries of autocratic rule, from the tsars to the Soviets, fostered a culture in which the state is seen as superior to the individual. My own conversations with Russians, and Chinese, support this view.

Normative democratization is the idea that democracy emerges from certain underlying moral principles, and that without those principles, any democracy is ultimately doomed to fail. In other words, the American architects of Japanese democracy realized a profound truth — that although democracy is technically a form of government, it is first and foremost a culture that prizes a specific set of values, and when they become instantiated in law, they tend to produce democratic systems.

Even in the presence of luxury and privilege, a false narrative of victimhood, repeatedly often and loudly enough, will convince nearly anyone otherwise.

The project of instilling the moral prerequisites of democratic governance — things like respect for individual rights, rule of law, and public reason — proved to be a relatively easy lift since Japan already had many proto-democratic values rooted in its Confucian-Buddhist ethical framework, which emphasized principles such as civic duty and harmony (和 wa) as well as group consensus (根回し nemawashi). And it is because of the phenomenal success of this experiment, and the untenable status quo both for Israelis and the children of Gaza, that I have previously argued for a similar approach in the essay “The Case for Colonizing Gaza.” That’s because the only solution there seems to be a kind of cultural revolution in which the dominant Palestinian values of antisemitism and sacrificing oneself and even one’s own children to the State are replaced with the values of tolerance, growth, and peace. Back in the 1950s and 60s, Americans understood this basic principle, were able to instill certain Western values in Japan, and the results simply speak for themselves.

The Japanese were literally nuked, yet they did not develop a debilitating national narrative about how some colonial Western power oppressed them. Instead, they studied Oppenheimer, invited him to speak, learned from him, as well as from America in every other way they could, or cared to, and in time, Japan went from being one of the world’s worst societies to one of its irrefutably best. So yes, when the film Oppenheimer came out in 2023, its release was delayed by several months and hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) did express some disappointment that the Japanese perspective was virtually absent. I don’t think that perspective was needed, but more importantly, the Japanese did not become deeply resentful, hateful, or violent toward Americans as a result of the war. Instead, they became one of America’s greatest allies and the Japanese public has since fallen in love with American culture and values, to their great reward. In the flash of a second, they became one of the most oppressed people in human history — then promptly rose above that fate to prove the merit of their character as a people who could not be held down.

This is a relatively rare phenomenon, and one that surely deserves more frequent praise. Many other cultures, as well as people on an individual basis, will become filled with hatred when horribly oppressed. Indeed, the mere narrative of oppression, even when false, is often enough. Even in the presence of luxury and privilege, a false narrative of victimhood, repeatedly often and loudly enough, will convince nearly anyone otherwise. Until recently, Gazans lived in a veritable beach resort, which Gazans themselves will tell you when they lament its loss, while in the same breath describing it, for political purposes, as an “open-air prison” where they received up to $6,800 per capita in aid, compared to the $555 per capita, adjusted for inflation, that Europeans received as part of the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after World War II. Similarly, you have black Americans such as Whoopi Goldberg complaining that in America, where she is a nationwide celebrity whose net worth is estimated at $30 million, blacks have it as bad as Iranians. I’m not making this up. During an episode of “The View” last month, co-host Alyssa Farah Griffin pointed out that in Iran, “the Iranians throw gay people off buildings.” Goldberg objected that America is no better. Griffin said, “I think it’s very different to live in the United States in 2025 than it is to live in Iran.” To which Goldberg replied, “Not if you’re black!” And if you been paying any attention, you know that this demented viewpoint is likely to be widely held by left-leaning black Americans.

Other salient examples here include Koreans, Irish, and Armenians. Each of these groups harbors intense and lingering hatred, at a remarkably high level of prevalence within their populations, for their respective oppressor groups — the Japanese, the British, and the Turks. Indeed, you are hard pressed to find a Korean above the age of 40, for example, who is not incredibly racist towards Japanese people. Though it bears mentioning that in each case, Palestinians and Armenians being the only notable exception, it is the political left within each of these groups that is the culprit. Anti-white racism is just as rare among Republican blacks as anti-Japanese racism is among members of whatever the Korea’s conservative party is calling itself this week. The point is, just as democracy is fundamentally a cultural phenomenon, so too is genuine resistance, which involves building up your own community against the forces that would seek to dismantle it. But if you are part of the problem and not the solution, that’s not resistance. That’s blind collaboration. That’s learned helplessness. But as the Oppenheimer taught us, culture can change — and with it, so can destiny.

If Oppenheimer stands for anything beyond physics and warfare, it is the notion that ideas shape reality.

The deeper lesson from Oppenheimer’s reception in Japan isn’t merely about forgiveness or pragmatism, though both played a role. It’s about the radical power of cultural transformation rooted in values that enable human flourishing. The Japanese did not wallow in grievance or use victimhood as a political identity. They looked inward. They recalibrated their moral compass. They adopted the civic virtues necessary to rebuild. This wasn’t assimilation by force, but cultural evolution by choice. The U.S. occupation may have laid the scaffolding, but Japan built the skyscraper. Contrast that with cultures that cling to inherited trauma as a badge of honor and identity. The result is never the justice they seek, but instead the rot of their own souls. And the more others lean into that narrative by trying to help, the worse it gets, and the more their resentment calcifies as cycles of blame replace the pursuit of excellence.

This is why victimhood as a political identity is pure poison, and why the best thing outsiders can do to help a community is to reject such framing. Otherwise, it becomes fetishized and corrosive, excusing failure and fostering tribalism. On an individual level, it is the opposite of resilience and maturity. If Oppenheimer stands for anything beyond physics and warfare, it is the notion that ideas shape reality, but culture determines whether we rise from the ashes — or bathe in them.

In the late 60's Frank Oppenheimer was my physics professor. During the time of the Vietnam War. He invited students to remain after class to discuss current events. As the class was attended primarily by engineering students, there were no takers. I'll always recall the profound sadness that accompanied J. Robert's brother. I made note of the human, emotional scars that remained. (And, as my father, was also a nuclear physicist, I looked there for something similar, which I did not find.) With respect to Gaza, one of my mentors in peacemaking shared with me a year ago that he had attempted to bring about movement with Hamas for over thirteen years. He concluded that it was not possible. The changes in Japan are not possible because of the heartened hearts of Hamas, a very different situation.

Brilliant! Cohesive! I have recently been cutting subscriptions to various podcasts, etc. I just resubscribed to yours. I appreciate how you think things through, honestly and articulate them so clearly. This is another one of your best.