On the meaning of faith

It's not irrational, but it is misunderstood

Often even the faithful define faith as belief without evidence. But being faithful to a friend does not mean blindly believing in their existence. It means being true to that friend. The word “faith” comes from the Latin fides, or loyal. And we have many reminders of this fact in our language today. That’s why we talk about audio recordings in terms of fidelity, meaning how true they are to the original, or a judge’s fidelity to the law, or marital fidelity. And it’s why the motto of the United States Marines is Semper Fi. Always faithful.

This is not the “faith” a child has in Santa Claus, which is actually make-believe and not faith at all, but rather loyalty to that which is holy. God and country, family and friends, a noble creed. Nor is faith simply thinking something to be true. I believe God exists, for example. Many unread people will unthinkingly define faith as an unquestioning belief in God’s existence without rational proof, but this is actually known as fideism, again from the Latin fides, meaning the idea that religious belief needs no rational justification. But faith is something else entirely. The core biblical verse on the subject is Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, chapter 2, 8-9:

For by grace you have been saved through faith and not from you but a gift of God and not from deeds so no one can boast.

Koine Greek had no commas or punctuation of any kind, but you get the idea. Or do you? Let’s look again. What Paul is literally saying is, by charis you have been saved through pistis. Greek social life centered around the concept of charis, or charity, but Greek charity was not compassionately giving to the needy without expecting anything in return. It instead referred to the kindness of the patron within Greek patronage culture, whereby wealthy citizens, or patrons, sponsored the poor or less powerful, funded public works, outfitted warships, and hosted athletic games. This was considered the duty of wealthy Athenian citizens. Indeed, orators such as Demosthenes often shamed patrons who shirked such civic duties, known as liturgies.

But their charity wasn’t free. These patrons expected loyalty, the same as any lord expects from any samurai or knight. Pericles sponsored festivals and plays for the people of Athens, who in return voted him in as general so many times he became the de facto ruler of the city. Xenophon says Cyrus lavished gifts on his soldiers, who in return were willing to lay down their lives for him. Paul uses the term charis because he wants to evoke the patronage structure in the minds of his Greek listeners. He wants them to think of God as the ultimate patron, just as other passages in Christian scripture cast God as the ultimate king, or ultimate father. These are simply different ways of describing God as the ultimate authority by reaching for the highest sort of human authority we can imagine. But the specific metaphor makes a difference.

Describing God as the Heavenly Father carries a loving connotation, whereas describing God as the Eternal King carries a connotation of power. What was Paul trying to communicate by framing God as a patron? He was saying something profound about our relationship with God and the nature of faith itself. Let’s consider the other half of the statement and the meaning of pistis, which does mean faith, yes, but in the sense of allegiance or loyalty. The Jewish historian Josephus, who lived during Paul’s life, used the term pistis to describe the loyalty between friends or military allegiances. Polybius, widely read in Paul’s day, used pistis to refer to loyalty between political allies. So when Paul says, “by grace you have been saved through faith,” a better translation would be, by patronage you have been saved through loyalty.

The idea that God’s grace comes freely, as some Christian traditions interpret this verse to mean, is not supported by the context. God’s patronage saves you, but by patronage you are saved through loyalty. In other words, the lord’s protection applies only to loyal samurai. Salvation is not an act of God, but a consequence of the relationship between the patron’s “love” and the client’s “faith.” The meaning of the message becomes clearer as we read on. The second part, “not from deeds so no one can boast,” is taken by many Christian traditions as meaning that salvation comes not by doing good deeds, but by faith alone.

This is of a part with credulity, fideism, lay faith, or what we might simply call Christian superstition. It may be dogma in some traditions, but it is heresy. The orthodox—literally right belief—viewpoint in Christian theology is not that simply by believing in a make-believe Santa god, without any evidence, one can therefore enter the Happy Place after you die and sing “Amazing Grace” with your dead loved ones forever and ever as angels fly around your heads. Atheists arrogantly poke holes in such arguments, but this is nothing more than a strawman. Or maybe it’s not fair to call it a strawman, since most Christians do, in fact, adhere to some version of superstitious Christianity, but it is the weakest of all “Christian” arguments.

I never saw any of the Four Horsemen of atheism take a swing at Kierkegaard, Tillich, or Barth. No offense, but Dennett’s fist would break off on Spinoza’s jaw. Instead, what we got were things like Richard Dawkins confronting Deepak Chopra on his linguistic deceptions or Chris Hitchens debating William Lane Craig. This felt largely performative. What was lacking was any good faith interrogation of religious concepts. Sam Harris tried by engaging Jordan Peterson, who does grapple with the deeper truths of Christian teaching, but Peterson struggled so much not to be pinned down to a straightforward “do you literally believe this happened?” question that, although he was walking an epistemological tightrope, he ended up looking like he was being dishonest and trying to have it both ways.

To be clear, the make-believe Ronald McDonald god promising an eternal toy if you buy the Happy Meal is not what Paul had in mind. The word for deeds Paul uses is erga, short for erga nomous. The word nomous means law, and this is the same nomous that you see in words like “astronomy,” where it means laws of the stars. Erga nomous, therefore, means the deeds of the law, or the deeds of Jewish law. That is, Torah observances. Paul is not saying one reaches salvation by believing in the existence of a God-man in the clouds without empirical evidence. But neither is he saying that good deeds do not lead to salvation. He is saying that you reach salvation by determination in your devotion to the Gospel, the “good news” that individuals, regardless of tribe or nation, can overcome their fate through spiritual awakening. Indeed, as New Testament scholar Matthew Bates and Yale religious scholar Teresa Morgan have explained, pistis means not only inner belief, but a loyalty that was lived out through one’s action across the span of a lifetime. A steadfast loyalty that survives brutal testing. In other words, a better translation for pistis might be grit.

People sometimes observe that Marxism bases its skeletal structure on this basic Christian premise: that the people can, through a certain consciousness of their condition, overcome vast oppressive forces through revolutionary struggle and achieve liberation of the oppressed such that they can defeat empires, sin itself, and even death. But it’s more accurate to say that Marxism rests upon the superstitious Christian assertion that some people are oppressed, and others, by virtue of their station in life, are the oppressors. Moreover, that you are saved by accepting a particular ideology — in this case, Marxism — into your heart. The problem is not what Nietzsche called the “slave faith” mentality so much as the abandoning of emphasis on living a good life and embracing of the idea that what you do is secondary to what you believe and what social status you hold as a patron, a slave, a Roman, a Jew, a white male, or a Black disabled trans Latinx.

This is why Paul often writes about pisteuein eis or believing into Christ. It is not about holding an assertion in the mind—God exists—but about living a particular way of life. He also talks about the need to have pistis Iēsou Christou, or Jesus Christ faith. Pay attention, he is not calling upon people to have faith in Jesus Christ, but to have Jesus Christ faith. See the difference? So when he says “not from deeds,” what Paul means is that you don’t have to follow the deeds of Jewish law to be saved. He is not saying you don’t have to do any good deeds or be a good person. After all, the question he was trying to answer at the time was not about whether a sociopath could find salvation, but simply about whether gentiles could do so. Specifically, Do gentiles need to follow Jewish law in order to join God’s covenant?

For Paul, insisting on circumcision, dietary laws, and purity codes as conditions of belonging would not only guarantee that his new church remained small, but it would also mean salvation is something one earns through Jewish identity. Paul was uncomfortable with the idea that spiritual enlightenment would be limited by ethnicity, and he instead argued that gentiles are included not by following the letter of the law, but by faith in God. Though again, just as the word jihad has a deeper and broader meaning of struggle that many non-Muslims tend to overlook, what Paul meant by faith was similarly something far deeper and broader—living one’s life according to a noble creed.

So where did the idea of blind faith come from? In De Carne Christi, Tertullian—the guy who came up with the idea of original sin and the Trinity—wrote about the idea that the son of God himself somehow died, “Precisely because it is absurd, it is credible.” This is often misquoted as, “I believe because it is absurd.” The other major influence was St. Augustine, who said, credo ut intelligam. “I believe in order to understand.” For him, faith was the necessary starting point that later opens the way to reason, rather than a rejection of reason. But these two statements got the ball rolling, and soon, Christians who did not have the time or cognitive capacity to plumb the depths of theological discourse on the meaning of reality instead comforted themselves with the notion that you didn’t have to work hard to attain spiritual enlightenment. You could just say, “I accept Jesus” and go back to the plow, rest secure in the knowledge that your soul is now saved.

But again, this isn’t what Tertullian or Augustine had in mind. Take Augustine’s claim. Before you can understand that two plus two is four, you must simply accept certain things on faith. Arithmetic rests on axioms, such as the Peano postulates and the rules of addition, which we accept without proof. In fact, you cannot prove them from within the system. You must assume them. That assumption is a kind of intellectual pistis that, once you make the leap, opens the door to nearly infinite understanding of objective facts about reality that you would not be able to otherwise grasp. Math works this way, but so does poetry. And faith. The notion of faith as grit, even when one’s will is broken on the cross of oppression, so to speak, is captured in the common Christian phrase, which Paul himself coined, “Keep the faith.”

That’s not about believing in something without proof. Even Augustine warned against gullible belief or credulity, credulitas, and praised devotion to rational understanding, which he called fides, or faith. Cicero rejected what he called credulity, or blind belief, in favor of fidelity to virtue. Similarly, Kierkegaard’s leap of faith is not make-believe in a Santa god, but the sort of leap you take when victory is uncertain, yet action required. In other words, bravery. The Hebrew word is emunah, from the root aman, meaning firm. For example, when we say Moses had “firm hands” during the Battle of Refidim, the word used is emunah. And, of course, emunah comes up repeatedly in the Psalms, but as an expression of loyalty and grit, not blind belief in some supernatural being. Furthermore, rabbinic teaching contrasts emunah with gullibility. Rambam (Maimonides) emphasized faith in God should be grounded in reason, never blind acceptance. And in Deuteronomy, we find the Shema, the Jewish declaration of ongoing faith—a daily affirmation, not a one-time event, serving as a reminder that faith is about living in an ongoing relationship with the patron of God.

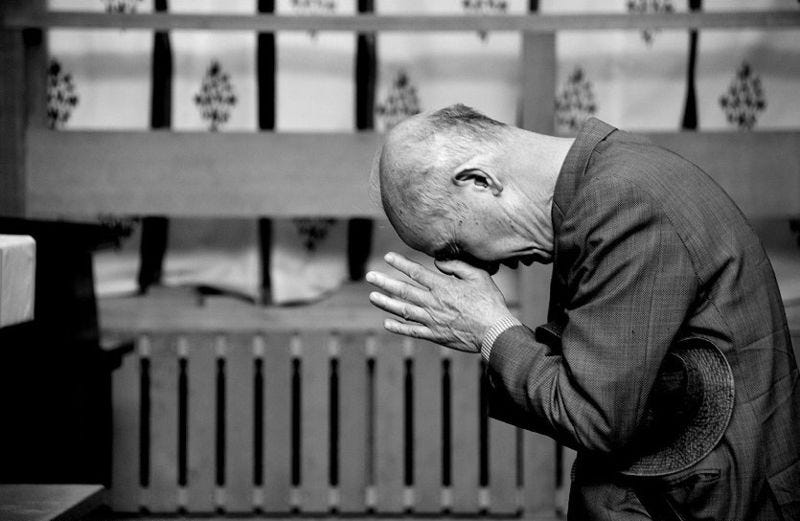

For Christians, aside from Paul’s letter, the doctrinal definition of faith is found in Hebrews 11:1, which says, “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” But even this is not a call for superstitious Christianity. The athlete has faith in her future self, even though that self does not exist, and she has no proof for it, yet this is not blind belief because her faith, in the form of devoted training, produces the evidence through victory. In a word, grit. Faith is not a child tossing a coin into a wishing well. Faith is a boxer who gets back up again, and their faith therefore becomes the substance of the victory they hope for, and the evidence of the champion not yet seen.

There is a discussion to be had around how to properly define God, if not as a supernatural being sitting on a cloudly throne above us, but it is enough for now to simply say that the message of faith is a message not of credulity, but of rational devotion to a noble cause, a loved one, or a nation. This is a devotion defined not by superstitious belief, by bravery and grit. So whatever your cause, if it be noble, then have faith, my friends. Have faith.

Faith is not necessarily irrational, but nor is it rational. Would one say that the Medieval Jew faced with a choice of accepting Christianity or being burnt at the stake would by reason choose to die? Yet so many did make that choice, I think, because the entire meaning of their existence was wrapped up in the idea that they were partners in a brit, a covenant with Hashem. And for what glorious purpose? Only the work of perfecting the world. And for this they chose Kiddush Hashem, sanctifying Hashem’s name through preserving the meaning of their lives. What to us might seem the act of a religious fanatic was instead a person choosing to live and die in a way that reflected a deep deep faith, not necessarily in the afterlife, but in the integrity of this life.

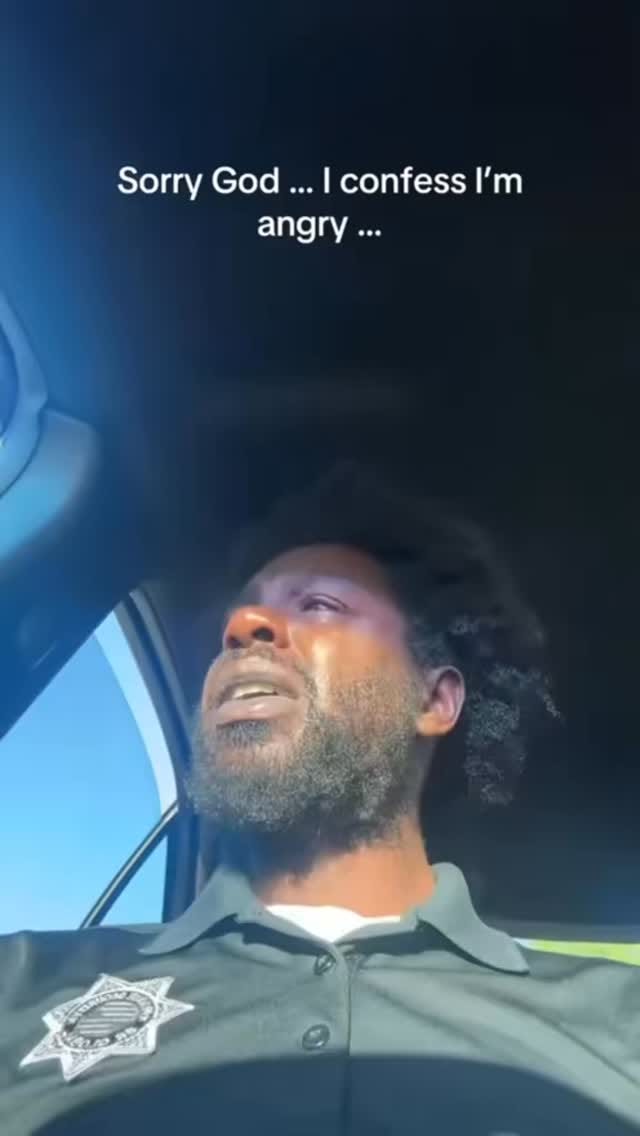

On a personal level, I think that faith even on a daily basis is neither wholly rational nor not. Rather, it seems to be, if anything, an intuition. Sometimes the world we experience does not seem to justify faith - I am thinking of our hostages being held for two years in the terror tunnels of Gaza. Yet, incredibly, some of the hostages found faith there, an intuition that their captivity was a challenge to find transcendent meaning even there. Even in less extreme circumstances, in our days of immersion in this physical materialistic world, of needs and lacks and distractions, those of faith reach beyond the rational and irrational to sense beyond senses, to intuit the holy that invests our time and space.

A beautiful essay David, and so fitting for these ten days of repentance.

Fascinating article.

In Hebrew, the words for Faith and Art are related. Faith is Emuna- Amen means believe, have faith- and Art- also craft- is Omanut. Artist is Oman. It is written exactly the same: אמן,with the identical root letters.

I believe - there we go, again, this is a belief, in this case, in my own intuition- that faith can be understood as an art of the creative “ spiritual” mind, also curative,one that strengthens our sense of reality and presence in this world, including a need for transcendence, and allows connection with a simultaneously wondrous and terrible world.

Faith grapples with a God yet to be fully revealed, the Biblical middrash of Jacob wrestling with God an actual prophecy , a sense of awe anywhere from Spinoza’s pantheism to physics’ quest for the “ One” unifying theory, perhaps a sense of this God even returned to our consciousness, and a humanity still in formation, many thousands of years away from redemption from its dark, savage nature, an understanding of process and history, even anthropology, and our own obtuse arrogance and narcissism believing - in an erratic kind of faith- that we already have all the answers. Before defining Faith, we would need to understand our own humanity and begin to perceive what God might be. The Absolute Generative Totality.

Israel, given a gift of positively transforming its collective

mind by the Powers that gift everything to all, an Israel deeply in love , awe and fear, and bound ( as per the root “religio”) to its God, never accepted that they were enslaved, abused , attacked , violated, mistreated, by every passing empire or tribe, the constant of Israel’s history from the get go in the Land of Israel, because God had unloved and abandoned them at a whim, and thus they were worthless. No, it was their fault, they told themselves, as they learned to self- blame and shame , but it was something they could fix. God never abandoned them. Their faith artfully created a mind-scape where their dignity and divine love were justified and protected, whatever the Earthly circumstances.

God had a special purpose for Israel and it was under the severe forge of the Divine that Israel was, as they themselves understood it, sanctified.

Israel was special, unique, fated to dwell alone, consecrated, strong enough in its understanding of the vastness and incomprehensible infinity of God, of the moral path, the ( partial)divinity of every human, not God itself but its worthy image, an acceptance of accountability, and the non-transactional duty to others, one’s neighbours, one’s kinsmen, the poor and disadvantaged, the strangers in the land, and also their enemies, whom Israel was commanded to help in times of hardship, though was not obligated to love, a utopian task. Compassion and mercy to all, though, were already in Abraham’s nature and dialog with the Almighty, one we too yearn for.

Today more than at any other recent time, Israel needs this kind of faith. “ Tikkun Olam” , repairing the world, a much later kabbalistic idea, was not a core faith of Ancient Israel, but being “ a light unto the nations” , “ a model, treasured people” was. And they knew it had a price.

Israel intuitively perceived how far ahead their thinking was, and accepted their painful ordeal of never ceasing to fight dearly for survival, opposed by the rest of the world, who would have preferred- and adopted- a slower pace in their moral evolution, which they demonstrate today by having swept even the liberal, morally founded West into a most regressive - not “ progressive”- old-new wave of Jew-and-Israel hatred, the same plague that infected the West since Israel’s faith and its Torah , written by Israelites for Israelites, was snatched and eviscerated ,

to diminish its moral demands of accountability .

The faith of Israel remains a faith in its peoplehood, its history and its ancestral self-chosen mission for good, its own “chosen chosenness”.

Not much of the supernatural there.A rational faith buttressed by an emotional millenarian memory.