On the government shutdown

Random thoughts about state failure and the origins of democracy

No civilization ever had a government shutdown in the modern sense. Empires suffered no funding lapses due to legislative deadlock, monarchs never halted the crown’s affairs because the throne and treasury could not come to terms, and the few times in history when a government actually did come to a stop, the result was usually civil war. But also, the fact that we even can have government shutdowns—despite the tragedy of furloughed federal workers, halted food-safety inspections, and stalled scientific research—is something of which we should be proud, in a sense, for it reminds us that we live under the dominion of no king. Rather, it is the price we pay for the separation of powers, specifically the division between Congress, which controls spending, and the executive branch, which carries out the government operations that use that spending. Seen in this light, our ongoing government shutdown is not a failure of democracy, but proof that we still have one.

Many are the paths one could trace back in trying to explain the history of how we ended up with a republic that occasionally snags, but my mind casts back to two starting points, both in London: the Gunpowder plot and the second marriage of Henry VIII. Growing up in the Bahamas as a bastard child of the British Commonwealth, we celebrated Guy Fawkes Night every fifth of November. Alongside Halloween and Christmas, it was my favorite holiday. Every year, my brother and I gathered old clothes, stuffed them with newspaper, and fashioned life-sized Guy Fawkes dolls on our beds. Then we carried them outside on our shoulders, tossed them onto the wild bonfire in the yard, and danced around the flames as the sparks lifted into the sky. Only later did I come to understand that we were reenacting our near annihilation, a single moment in time when the West peered over the edge and almost didn’t walk back. A civilizational point of no return.

A colorable argument can be made that Henry VIII’s penis did what no army could and tore London from Rome, that his libido was a political force, that his inability to keep his breeches buttoned, combined with his possible infertility, gave birth to democracy as we know it today. It began in 1527, when Henry petitioned Pope Clement VII for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, his late brother’s widow, after she failed to produce a surviving male heir. Henry argued that God was unhappy that she had been his brother’s wife, indeed that this violated divine law, and therefore God had denied them a male heir. But when the Roman Catholic Church said no to his annulment request, Henry rejected papal authority, broke from the Church, and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England.

In 1534, Parliament recognized his right to supremacy, giving him the right to his marriage to one of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting, the bewitching Anne Boleyn. Catholics who refused to recognize Henry as their new religious leader were branded traitors. Anyone who did not attend Anglican services had to pay heavy fines. Harboring a Catholic priest was punishable by death. Catholics were barred from universities and public office. Within a few decades, priests were executed simply for performing Mass. In his 1605 play Measure for Measure—an eerily prescient critique of surveillance states guided by censorial virtue signaling—Shakespeare commented on state oppression in a line that became one of the great Renaissance aphorisms on the abuse of power, writing in Act II, Scene 2, “It is excellent to have a giant’s strength; but it is tyrannous to use it like a giant.”

That same year, a group of Catholic terrorists rented a cellar beneath the House of Lords and packed it with 36 barrels of gunpowder. They were sick of the way Catholics had been brutally persecuted, all so that the Heretic and the King’s Whore could have a romp. They left Guy Fawkes, an English soldier and explosives expert, to ignite the fuse during the opening of Parliament—when the king, his family, and the entire political elite would be present. But an anonymous letter betrayed them, Fawkes was discovered, confessed under torture, and the plotters were hunted down and executed. Over the years, the symbolism of Guy Fawkes has evolved from that of a terrorist burned in effigy to a folk hero of resistance against tyranny, celebrated most famously in Alan Moore’s graphic novel V for Vendetta. But however you see him, villain or hero, the ritual reminds us that the state can die suddenly, and must be guarded vigilantly. But also, that when it “becomes destructive,” as Thomas Jefferson later wrote, “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.”

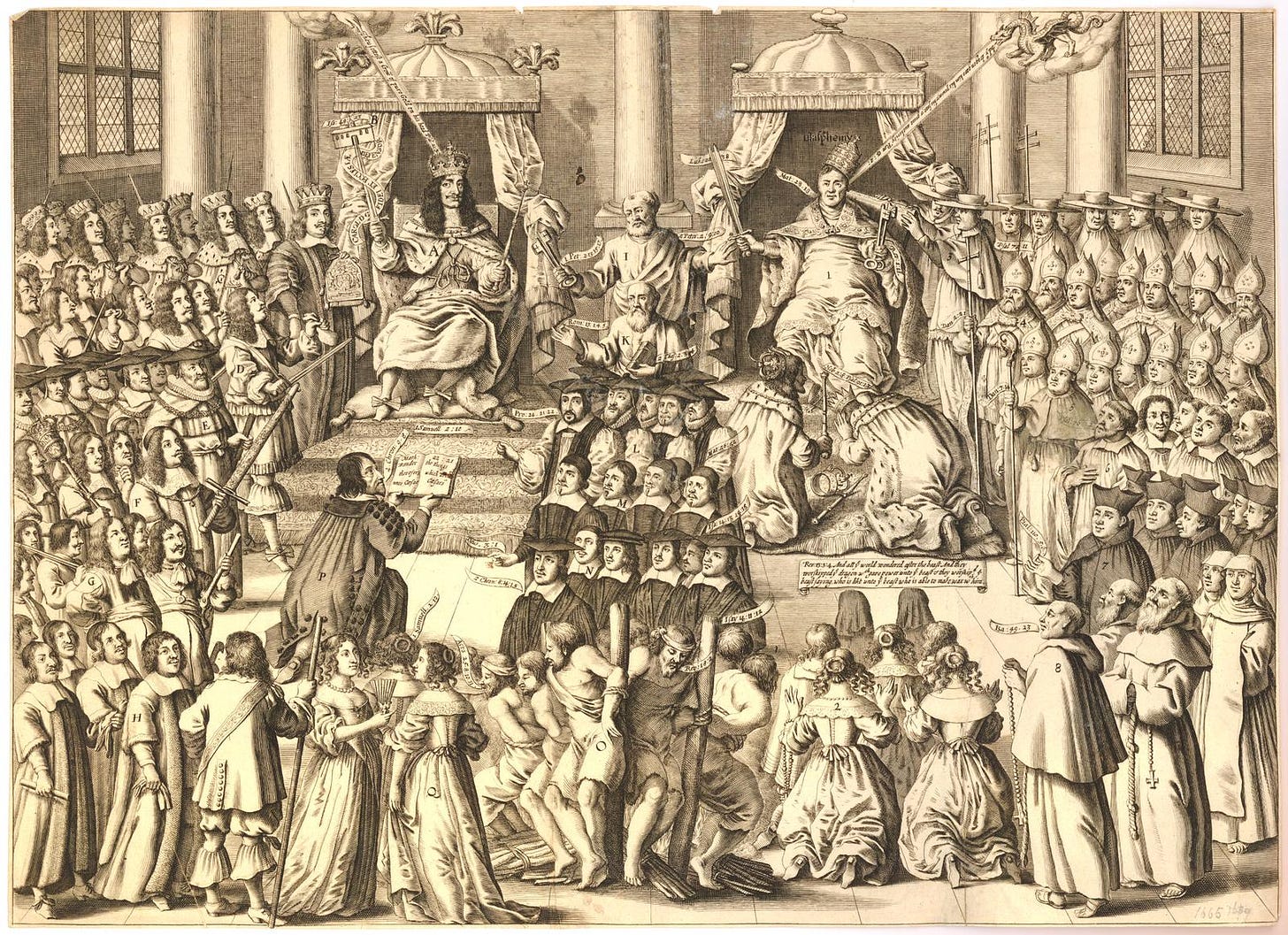

In those lines of American scripture, Jefferson drew heavily from John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, written in 1689, which held that government is a social contract that exists only by consent of the governed, that people possess natural rights to life, liberty, and property, that when government breaks this contract by violating those rights then rebellion is not chaos, but the restoration of moral order. Locke composed the Two Treatises of Government during the Glorious Revolution, which was the culmination of decades of tension between monarchy and Parliament, Catholicism and Protestantism, absolute and constitutional power. Parliament overthrew James II, who had claimed that divine right trumps parliamentary consent, and Locke’s purpose was to justify the overthrow of a tyrannical monarch, rejecting the divine rights of kings and laying out a new political philosophy for legitimate government. As he said:

Men being, as has been said, by nature, all free, equal, and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent. The only way whereby any one divests himself of his natural liberty, and puts on the bonds of civil society, is by agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community for their comfortable, safe, and peaceable living one amongst another, in a secure enjoyment of their properties, and a greater security against any, that are not of it. This any number of men may do, because it injures not the freedom of the rest; they are left as they were in the liberty of the state of nature. When any number of men have so consented to make one community or government, they are thereby presently incorporated, and make one body politic, wherein the majority have a right to act and conclude the rest.

The idea was not entirely new. Locke pulled from Aristotle, who had anciently argued that governments exist to achieve the good life and that when rulers govern for their own benefit, regimes become perversions—tyrannous—and lose legitimacy. In De Legibus and De Re Publica, Cicero taught that unjust law is no law at all. In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas said rebellion could be justified against a tyrant who acted “against the common good.” But when Locke wrote that rulers who break natural law “put themselves into a state of war with the people,” he was invoking more immediate influences. We all remember that in his 1651 book Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes argued that outside the gates of government and law, we find “the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” But few of us remember what he was getting at here. His bigger point was that since life outside the law was hell, rebellion was irrational because peace under any ruler was better than the chaos of war.

Locke’s Second Treatise was in many ways a rebuttal to Hobbes. But Locke’s philosophical innovation was to make rebellion a logical consequence of contract theory rather than a theological exception. He turned centuries of moral and religious debate into a blueprint for constitutional democracy, writing, “When government violates natural rights, it dissolves itself—and sovereignty returns to the people.” That philosophical chess move is what made Locke revolutionary—and why Jefferson, Madison, and the American founders saw him as the intellectual godfather of liberty.

England, and the Bahamas, mark each November 5 with bonfires and effigies, burning Fawkes and his co-conspirators and dancing in the long shadows of memory of how close the kingdom had come to destruction. In response to Fawkes, Parliament tightened laws, demanded more oversight, and emphasized the king’s accountability to the realm. The idea took hold that “faith and government alike must be held in public trust.” A generation later, that belief hardened into confrontation when Charles I, who had inherited his father’s belief that he ruled by God’s will, not parliamentary consent, demanded taxes for wars against Spain and France—and Parliament, which had inherited a sense of its own power after decades of asserting oversight in the wake of the Gunpowder plot, refused.

In a fury, the White King dissolved the legislature and proceeded to rule alone in what the British call the period of Personal Rule, or the Eleven Years’ Tyranny. But unlike a modern dictator, he ruled oppressively, not murderously. In fact, he ordered the killing of no more than probably a dozen people, if that. One was Alexander Leighton, the Puritan writer who criticized bishops. The Star Chamber ordered him whipped, branded, his nose slit, and his ears cut off. Another was the Puritan lawyer and writer William Prynne, who in his massive tract Histriomastix condemned stage plays, actresses, and public entertainment as immoral. As fate would have it, Queen Henrietta Maria, Charles I’s wife, happened to be performing in a court masque at the time, and so his attack was seen as an insult to the queen herself. The Star Chamber sentenced him to life imprisonment, disbarred from the legal profession, pilloried, branded “S.L.” for seditious libeller, and his ears cut off.

But reading this, I am reminded of Henry VIII, who similarly refused to acknowledge a power other than his own because it said no to something he wanted to do, and how that set the stage upon which these later players all strut and fret their hour, as Shakespeare would say. And so began the struggle for power, and the emergence of a system to keep it in check.

Remember, Remember! The fifth of November, The Gunpowder treason and plot; I know of no reason Why the Gunpowder treason Should ever be forgot!

The attempt of Charles to govern alone did not go well, and eventually resulted in the English Civil War. The memory of that period haunted later generations. When James II—the one Locke saw overthrown—later tried to assert royal authority, Parliament tried to limit his absolutism by tightening the purse strings. He refused to compromise, was ousted, and the result was the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (so named because it was relatively bloodless). The silver lining was, Parliament then forced William and Mary to accept the Bill of Rights in 1689, establishing that the monarch could not levy taxes or suspend laws without Parliament’s consent. In other words, it fixed parliament’s supremacy over finance. It also established “freedom of speech and debates”—within Parliament, that is. But hey, it was a start. It also established other familiar rights: The right to petition, the right to fair trial, even the right to bear arms—for Protestants. It was the first time individual rights and parliamentary supremacy were formally enshrined in law, creating the constitutional model that contrasted sharply with absolute monarchy on the Continent.

The American colonists were British subjects. Their arguments were built directly on English constitutional precedent. They saw George III’s actions—taxation without representation, arbitrary laws—as violations of the rights of Englishmen, as secured since the signing of the Bill of Rights of 1689. Indeed, colonial pamphleteers repeatedly cited the English Bill of Rights as proof that kings must obey the law and that citizens have inalienable liberties. The Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) drew upon this Anglo-constitutional tradition, but the radical innovation here was that it expanded the concept to assert that rights were natural, and not merely granted by Parliament. So the American Revolution was, in one sense, a rebellion in defense of the English constitution—until it became something new, a radical republic grounded in universal rights. What had begun as a defense of tradition became a revolution.

This, in turn, inspired the French. French officers who fought in the American Revolution, most famously the Marquis de Lafayette, carried those ideas home. In 1788, when France’s Estates-General refused to approve new taxes unless reforms were made, the government was left literally unable to pay its bills—soldiers went unpaid, public works halted, credit collapsed—leading to the outbreak of the French Revolution. Once again, the inability for crown and parliament to come together had resulted in civil conflict. The following year, Lafayette helped draft the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, explicitly modeling it on both the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. American revolutionary texts circulated widely in Paris, and Thomas Jefferson, then U.S. ambassador to France, consulted on early drafts. The Declaration extended English constitutional liberty into a universal human creed, and a through line could be traced from this universal new creed all the way back to Henry VIII.

Here’s a final example. In 49 BC, Julius Caesar, the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, led his 13th Legion over the Rubicon River, which marked the legal boundary between his province and Italy proper. This was a flagrant violation of Roman law, which strictly forbade any general from bringing his army into Italy. Doing so was considered treason. So once he crossed the Rubicon, there was no going back. He had effectively declared war on the Roman Republic and could not return to the Senate without being tried and executed for treason. The historian Suetonius records that, as he crossed, Caesar uttered the words, Alea iacta est. The die is cast. He was now in that liminal moment between having thrown the die and waiting for it to tumble to a stop and show a number. The good Greeks have a word for moments like this, inflection points when time seems to freeze and fates are decided. They call it kairos, which just literally means time, and we get another famous expression from this particular kairos—when people today say someone is “crossing the Rubicon,” they mean taking a decisive and irreversible step.

Wisely, Shakespeare used anachronistic allegory to comment on topics of the day without tempting the wrath of the throne. His Roman plays, such as Julius Caesar or Coriolanus, are often said to hold up a mirror to Elizabethan or Jacobean politics by interrogating questions of tyranny and republicanism under the guise of history. When he wrote, “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears,” Queen Elizabeth I was elderly, childless, had not named an heir, and England lived in quiet terror of a power vacuum—with haunting but undeniable parallels to Rome after Caesar’s assassination. In Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic, the English historian Tom Holland holds a Roman mirror up to America. Indeed, Holland once said in an interview, “When I wrote Rubicon, I pitched it to publishers as being a mirror held up to the present.” Holland makes the case that this kairos wasn’t just an inflection point for Caesar, but that for all of Rome, the die was now cast. This violation was the beginning of the breakdown of Roman constitutional norms, with Caesar being inspired by how Lucius Cornelius Sulla marched his legions on Rome because he refused to admit political defeat.

You wouldn’t be crazy, by the way, for thinking Holland is holding a mirror up to America with a specific nod toward January 6, except that the book was published in 2005 and was actually about learning to take internal threats to liberty seriously. As he wrote in the preface, “The story of the Republic is, in essence, the story of how a civilization committed to liberty and the rule of law came to destroy both.”

And how does that happen? As we have seen, in recent history, it tends to happen when rulers seek to take too much power for themselves, parliaments stand in their way, and governments grind to a halt. So although our current government shutdown is, as I said at the top, something like what folks call a first-world problem, it is nevertheless an extremely dangerous situation. But as for Holland’s take on Rome, I disagree. I think the Rubicon moment for Rome was not, in fact, the literal Rubicon itself. By then, the state was already hollowed out, the Senate had ceased to function as a deliberative body (and was instead a battlefield between senatorial elites and Roman generals), and constitutional norms had already eroded significantly. The moment the die was truly cast, in my view, was during the Senate deadlocks of that same year, between the senatorial elite and Roman generals, resulting in institutional paralysis. Here, repeated stalemates over land reform, debt relief, and citizenship drove both populares and optimates to violence. Every aspect of society, even the justice system itself, became a weapon used by political factions. Once that took place, Rome’s constitution stopped being adaptive. They were a people mighty but divided. Cicero himself lamented that the Republic was “a name without substance.”

From the Gunpowder plot and Henry VIII’s defiance of Rome to Charles I’s war with Parliament, from Caesar’s crossing the Rubicon to Congress’s shutdown, the story is always the same. When rulers and assemblies clash, this represents the living tension on which democracy depends, and which keeps tyranny at bay. Our government shutdowns are massively destructive, but they are also the faint crackle of that electric line, a reminder that we live not under the dominion of one will, but in the fragile, dangerous, necessary balance between many.

While your argument is cogent, I'd submit it's got very little to do with the current Washington mess.

Let's propose that the current government shutdown isn't driven by the chief executive, but a wanna-be chief executive who threatens the current leaders of both the House and Senate with primary challenges in 2026.

The wanna-be's name is Alexandra Occasio-Cortez, and both Chuck Schumer and Hakeem Jeffries are in her Brooklyn district and thus vulnerable to her threats. She has been on the record as threatening both Schumer and Jeffries with primaries next year if they don't comply with HER wishes, HER policies and demands. If this is true, the current "tyrant" isn't in charge of anything, but directs everything.

If true, AOC is the current "leader" of the US and, indeed, a tyrant because of political infighting. How does that fit into your thesis?

Nice review. I'd like more analogies to today, but I imagine that is a later post/book. One caveat though: a lot of these fights are fights between aristocrats and rulers. And a lot of them had to do with aristocrats pissed off about paying for ambitious executive wars, which their various monopolies could not be pressed hard enough to fund. Once that was resolved, British became a strong state, and eventually an empire. Here the tension is not between the aristocrats and the king, but between many agents and the bureaucracy that has been growing since Francis Bacon. The civil services, scientific labs, academic departments, professional societies, etc. The authority of expertise is being radically challenged. Whether that is good or bad is getting to be besides the point. What is becoming evident is that what's emerging as the natural challenge to this dispersed order is the strong man. The strong man represents not just a champion against an established order, he represents a new knowledge model, which is, we identify with the strong man, and the strong man identifies with us, via common sense. So, while yes, we can find analogs to executive friction in the past, I think this is something relatively new, and a strong reaction to an equally strong tendency.