Interview with Srdja Popovic

Talking Ukraine with the man who saved Serbia

The late Christopher Hitchens once wrote, “Milosevic began and ended, as all such dictators do, by ruining his own people and degrading his own country.”

Slobodan Milosevic was born in 1941 in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. When he was 21, his father, an Orthodox theologian, killed himself. One year later, his uncle Milislav, a major-general in the Yugoslav People’s Army, killed himself. When he was 31, his mother Stanislava, a communist school teacher, killed herself.

He studied law at Belgrade University, joined the socialist youth league and became the head of its ideology committee. He was a leader in the Serbian Communist League. He was head of the Serbian Socialist Party. In 1989, he became president of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. He changed the constitution, centralized power, censored the media, stoked Serbian nationalism, formed death squads and let his friends and political allies run the financial sector. As Hitchens wrote, he was the “maggot at the heart of the state that just keeps eating remorselessly away.”

The term “ethnic violence” was coined to describe what came next. In 1995 during the Bosnian War, Serbian Republic forces under General Ratko Mladic, the “Butcher of Bosnia,” massacred more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys, raped women, destroyed homes, expelled up to 30,000 people and committed wanton acts of torture. The town of Srebrenica experienced the worst of the Bosnian genocide.

Milosevic died in a prison in The Hague in 2006 from a heart attack. Two days later, Hitchens wrote an essay for Slate titled “No Sympathy for Slobo: Let’s not forget Milosevic’s many crimes,” wondering whether the tyrant’s sudden passing might allow the memory of his evil to fade. No, Hitchens said, video archives of the atrocities would make denialism or revisionism impossible.

I share such concerns over genocidal amnesia regarding communist leaders. That was the point of my now infamous Seattle Times column. But I do not share his faith in technology, and certainly not video. Hitchens never lived to see deep fakes, hyperreal synthography or text-to-image AI programs such as Midjourney, not to mention the infestation of nihilist killdozer tankies on Twitter.

The great British polemicist then weighed Milosevic’s psychological evil against that of contemporary tyrants. He wrote, “Milosevic did not have quite the psychopathic power of a Saddam Hussein or an Osama Bin Laden.” But for Hitchens, this actually made Milosevic worse. More dangerous. In fact, “he was that most dangerous of people: the mediocre and conformist” who “embodied the banality of evil.”

In 1999, Milosevic became history’s first sitting head of state to be charged with war crimes when a UN international tribunal indicted him for religious and racial persecution, torture, murder and genocide, among other things. The only beautiful thing about any of this is that his demise came at the hands of a democratic uprising. Demonstrations choked the streets, overwhelming the government, until Milosevic stepped down and was arrested. The 2007 film The Hunting Party, about a group of journalists who track down Bosnia’s greatest war criminal, ends similarly. If you haven’t seen it, I’d skip the clip below and watch the whole film.

It was Serbian activist Srdja Popovic who lit the spark of revolution. In 1998, Popovic and a group of students founded the nonviolent resistance group Otpor, or “resistance.” Popovic led the group, using creative methods to circumvent Milosevic’s censors. For instance, Otpor put a barrel in a public area with a picture of Milosevic on it and a sign that said if citizens dropped a coin in the barrel they could bash the photo with a nearby pole. Police had no one to arrest so they arrested the barrel.

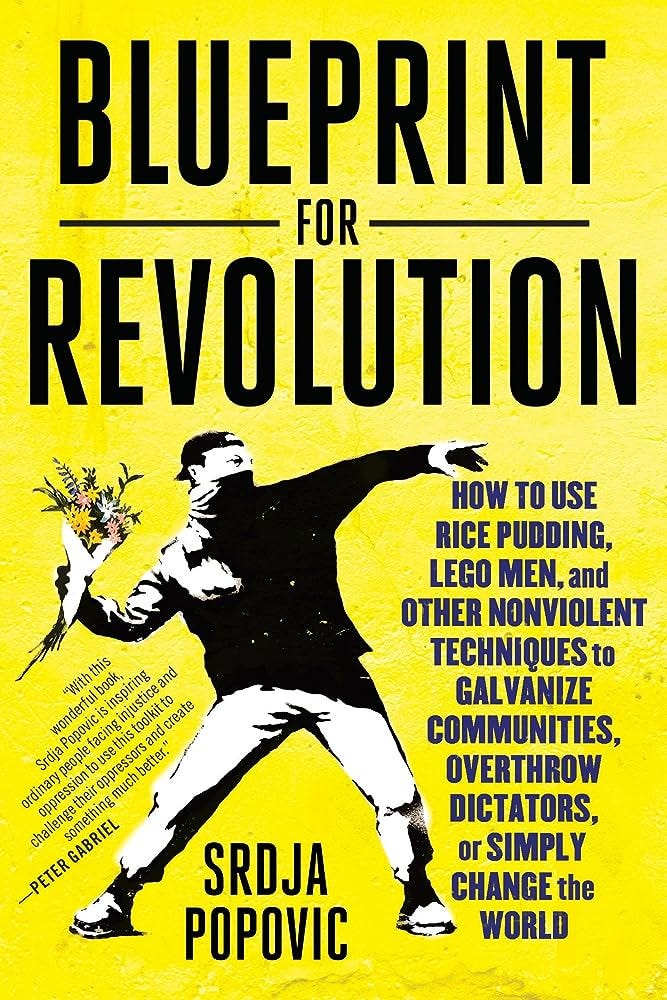

In 2003, he and former Otpur member Slobodan Dinovic co-founded the Centre for Applied Nonviolent Actions and Strategies (CANVAS), which trains activists in over 50 countries including Venezuela, Iran, Eritrea and Ukraine. Popovic has also written about his methods and is the co-author with Matthew Miller of Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World.

In 2011, Foreign Policy listed Popovic as one of the “Top 100 Global Thinkers” for helping inspire the Arab Spring protests. In 2012, The Wired listed him as one of the “50 people who will change the world.” He has also been discussed as a viable candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize.

On April 7, 2022, just two months after Russia invaded Ukraine, I flew to Europe to cover the war and ended up writing about Ukrainian refugees for New York Magazine and The Nation. During this time, I noticed Ukrainians using creative memes and videos to garner Western attention and recognized Popovic’s fingerprints. I contacted him and he spoke to me about Ukrainian fighting spirit, why Chinese don’t rise up, Putin’s fate, the psychology of genocidal violence, the economics of Soviet arms deals, tactical mapping and much more.

My plan had been to quote a few lines for a story about Ukrainian protests, but the story was never published and the recording was almost lost to time. It’s a great interview and Popovic is a hero of mine, so I’m glad it will finally have an audience.

I wonder if Milosovic is in power today, how would he use technology to help him maintain his grip in Serbia.