Commonplace thoughts

What do I read in my free time

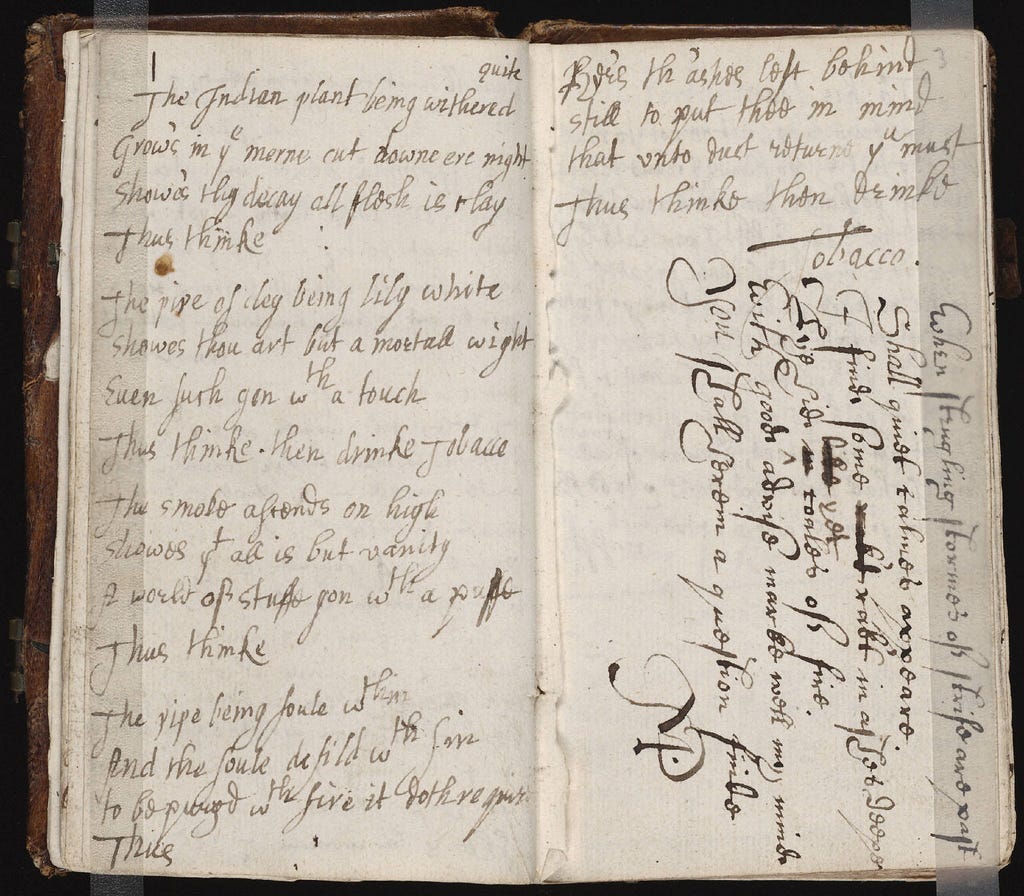

Commonplace books were a glorious and sacred thing that almost no one knows existed anymore. These were the scrapbooks of the Renaissance. More than that, they were family bibles. I don’t mean family copies of the Bible, but the private scripture of a single home. Just as Jewish scripture preserved the inner life of Jews in ancient Israel, compiling events, prayers, poems, and laws, commonplace books played a similar role for Renaissance Christian families in England, Italy, France, and Germany. Instead of commissioning costly bindings, families recycled existing volumes by bleaching the pages and filling them with treasured personal reflections, family lore, popular proverbs, coveted recipes, or whatever else they wanted. Reading a really good commonplace book is an amazing experience, like watching an entire family overhead cast their line into time, and seeing the ribbon of their story illuminated in a thousand moments, flashing in the sun. A joke, a random thought, grandma’s secret recipe. It reminds me of the monologue from American Beauty:

I had always heard your entire life flashes in front of your eyes the second before you die. First of all, that one second isn’t a second at all. It stretches on forever, like an ocean of time. For me, it was lying on my back at Boy Scout camp, watching falling stars. (gunshot) And yellow leaves from the maple trees that lined our street. (gunshot) Or my grandmother’s hands and the way her skin seemed like paper. (distant gunshot) And the first time I saw my cousin Tony’s brand-new Firebird. And Janie. And Janie. And Carolyn. I guess I could be pretty pissed off about what happened to me, but it’s hard to stay mad when there’s so much beauty in the world. Sometimes I feel like I’m seeing it all at once and it’s too much. My heart fills up like a balloon that’s about to burst. And then I remember to relax and stop trying to hold on to it. And then it flows through me like rain, and I can’t feel anything but gratitude for every single moment of my stupid little life. You have no idea what I’m talking about, I’m sure. But don’t worry. You will. Someday.

Yet commonplace books are not celebrated as they should be. Most English majors never read them. No movie was ever adapted from one. Even you, my discerning reader, have likely never heard of them. But they are a fountainhead of beauty, each one a peek into the private life of a family that once lived, and perhaps still does. In any event, I recently asked, “What should I write about next? Any question, any topic, any field.” And you answered. So here are my commonplace thoughts.

What really good novels are being published now (and by whom?). We see a lot about the gate keeping of publishing - DIE efforts and boy oh boy has some dreck been released - but I’d love to hear what you read.

I may not be able to give a very satisfying answer to this, but I can share something about my love of books. When I was a boy, I read indiscriminately. I lived in books. I fell asleep between pages. Literally. You know the rich vanilla smell of an old book? That’s not just a creative description. It’s actually vanilla. To be precise, vanillin, which is the compound that gives vanilla its scent. People used to make books out of cotton or linen rags. If stored properly, such pages last forever, which is partly why volumes from around the 1400s are often in better condition than those from the 1800s. In the 1850s, publishers began mass-producing books on wood-pulp to save on costs. Wood contains a natural polymer called lignin, and as lignin breaks down, it releases volatile compounds. Floral ethyl hexanol, almond-scented benzaldehyde, and sweet vanillin. But by the 1930s, librarians and archivists began to notice that acidic wood-pulp decays quickly. By the 1970s, publishers and printers began transitioning to acid-free or alkaline-buffered paper, which smells like ink and glue, with a sharp chemical note. As a result, you can actually date books by smelling them because if a text smells earthy, it was likely made before the 1800s, if it smells like vanilla, it was made sometime between roughly 1850 to 1970, and if it has a chemical odor, it was made after the 1970s. So the next time you smell book vanilla, remember that every book ever made in this period will one day lose its smell, like the warmth of fresh bread, or the scent of a dead loved one fading from their clothes. Appreciate it while you can. Future generations will never know the fragrance of this flower.

My meandering point is simply to say that book vanilla was the fragrance of my youth, yet I’m no good when it comes to recommending books because my reading habits are somewhat unusual. Drink enough wine, and spend any time thinking carefully about it, and you’ll eventually develop a palate for it, with or without formal training. Read enough books, and if you’re a discerning person, you’ll come round to the same conclusion as the rest of the literary world, which is that the same few writers really are objectively the best, and once you land there, the Canon now becomes your permanent playground. You may venture outside from time to time, and you will have guilty pleasures — mine included Piers Anthony, Orson Scott Card, Christopher Pike, Stephen King, and Michael Crichton. But most of your reading will be done within the Canon because there is no better writing, and it may not always be fun to read Virgil or Chaucer, but it is edifying, and besides, fun is not a good gauge for what will prove nutritious to the soul. Rather, I have found that if I force myself to do a thing long enough, eventually the enjoyment comes with familiarity and skill. The better I am at it, or the better I know it, the more I tend to enjoy it. Consequently, when I do read fiction, I select from Harold Bloom’s list of the Western Canon, and I have devoured much of this list in my life. At the same time, I love science, and as a child, I used to read a lot of pop science books. Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach, Pierce Howard’s The Owner’s Manual for the Brain. But eventually, as with literature, you develop a taste, and you begin to seek out more richly detailed characters, more vividly described worlds, and in science, more granular data.

So I ended up haphazardly reading undergraduate textbooks in a few random fields, until I realized this wasn’t the way to go. Then I wrote down all the major arts and sciences, googled which universities had the world’s best department for each, found their syllabuses, obtained the textbooks, often did the homework, and watched online classes, if available. In essence, I tried to reconstruct the course as closely as possible, and I did this for pretty much every subject I could think of, to the 100 level at least, and familiarizing myself with the foundational concepts and skills. I used to keep all my notes in a folder titled The Basics, because it was a collection of all the basic concepts from each field. And I would read from it like some folks read the Bible.

Two things resulted. First, I picked up a ton of knowledge, and like an idiot, promptly forgot almost all of it. If I have one great insecurity or thing about myself that I would change, it’s my rotten memory. Second, I learned to see academic fields not as fields so much as foreign languages, and if you learn the vocabulary, you can navigate the territory relatively easily, so even in cases where I don’t recall a ton of the subject matter and wouldn’t pass a basic exam, I do still have the general grammar structure in my mind, so to speak, meaning that I have a grasp on how to think like a botanist, how to see the world like a chemist, or how to talk like an anthropologist, if that makes sense. And, to the degree that my interest in the subject persisted, I kept reading, right into graduate work for some of my most favorite subjects, but again, this is a second-rate, jerry-rigged education stored on a dunce-cap flash drive. I am no expert in these areas and would never pretend to be, but I am at least fluent enough in the language to read, and that’s all I ever wanted to be able to do with it.

My goal is what you might call spiritual enrichment, what the Greeks called eudaimonia, or simply, the good life. All of which is to say I’m not very good at recommending books because it’s mostly this kinda stuff, news articles, or whatever I happened to pluck from one of my shelves. And if you haven’t read your way up to it, a lot of this stuff feels like schlepping through a three-page footnote in a tax code policy. But, if you speak the language, it’s more endlessly fascinating and addictive than TikTok, and I really think more people should try it. I hope I’ve managed to make the concept sound appealing, instead of super pretentious and weird.

My personal philosophy is to pick your hobbies, and your reading and eating habits, and that of your children, not according to what you enjoy, but according to what’s truly Good. Because enjoyment will come, believe me. But if you lead with enjoyment, the Good may never come. So I make myself read things until I like it, just like I make myself do certain exercises, or practice certain musical instruments, or languages, and the fun comes later, when I’m in good shape, or can play a guitar song for my daughter, or speak to my friends in other countries. Or, for example, read this study, showing that we probably exist in a local void after all, which is a basically a pool of lesser density in the vast starry expanse, stretching 2 billion lightyears wide, with us at the center. Or this one, which explains that it turns out dark matter really does shape the universe the way our best models predict, existing in a cosmic web in which galaxies sort of “breathe,” constantly inhaling gas as fuel and blowing enriched gas out. I mean, WOW. Pretty mind-blowing stuff. But if you click those links and read the titles, you’ll see what I mean about pretentiousness and tax code.

In any event, what have I been reading lately, other than the above, or children’s books at bedtime? I’ve recently been reading the odes of Horace and, because I was in Lima last week, I was trying to get my daily news in Spanish, mostly from El Comercio, including columns by the Peruvian Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, who died in April, such as this essay, in which he argues that the unexpected success of Hemingway’s Fiesta turned old Papa Hem into the most popular American writer of his day. That said, even though I have failed to answer your question, I hope at least I succeeded in finding a way to make the answer interesting to read.

And, while I can’t recommend any good recent books, I can recommend a very good recommender of books. His name is Aaron Gwyn, an American author, professor, and my favorite literary follow on X. He’s recently been posting the four best American novels of each decade, as well as the four best American novels of the 21st century so far: Philipp Meyer’s The Son, Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, and Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai. I haven’t read any of these books, but Gwyn’s taste and mine are fairly aligned, so I imagine I’d love them, and perhaps you might too. Best of luck, and if you do pick up one of those books, I’d be delighted to hear what you think.

The smell of aging paper is called bibliosmia, just so you know; yes, it has a name. And were you aware that HP Lovecraft kept a Commonplace Book? I only know because one of my oldest friends edited an annotated version.

Thanks for the tip about Aaron Gwyn on X. That lead me to all kinds of interesting literary and movie nuggets. One of which is an article about Cormac McCarthy which was fascinating.