Berlin by the Sea

A reporter's travel notes from Israel

In October 2011, at the age of 31, I left my home in Copenhagen and traveled to Sweden, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, and Czechia. Eventually, I made my way to Israel. My plan, at first, was to visit Israeli friends who I had met while traveling China, particularly the ones I had come to know while staying at Buddhist monasteries or Shaolin temples, where there were many long and tired nights with nothing to do but stretch and talk by candlelight, and many lasting friendships were formed.

Soon, I found myself pulled deeper and deeper into Israeli history, politics, and culture. I ended up living there for most of the year, initially spending time in Haifa and Jerusalem before moving into an apartment in Tel Aviv, right on Rothschild Boulevard with all its porch parties, ficus trees, and Bauhaus architecture. After a while, and without much effort, I fell in love — with a girl, the people, the country. And although it didn’t work out with the girl, my relationship with the people and the county has only grown deeper since.

As it happened, I had chosen a particularly tumultuous time to visit. In August, a young Palestinian had carried out the Tel Aviv nightclub massacre. In September, the month before I arrived, Turkey expelled Israel’s ambassador, thousands of rioters in Egypt forced their way into the Israeli embassy, and Israel evacuated its embassy in Jordan. When I finally landed, the housing protests, one of the largest protests in the nation’s history, were raging. On October 18, nine days before my arrival, Hamas released the IDF soldier Gilad Shalit after five years of captivity. But the prisoner exchange also included Yahya Sinwar, the future mastermind behind the October 7 attacks. I later wrote about the ordeal for openDemocracy.

But this is not the story of my journalistic work in Israel. As one who has covered the subject for over a decade, I was delighted to find the following notes at the bottom of a box, and wanted to share them with you, dear reader. These are my first impressions, thoughts, and experiences upon discovering a new country. This is not a journalistic report, but a love story.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

My friend picked me up at Ben Gurion Airport and took me to eat what he claimed was the best hummus in the world. We went down to HaDolphin Street in Jaffa where we ate at a place called Abu Hassan, which is possibly the oldest and most famous hummus restaurant in Israel, and therefore maybe the best in the world, but certainly the best this boy has ever had. Then we went to the beach for surfing and kung fu, practicing the old forms we had studied at the Shaolin monastery in rural Yunnan.

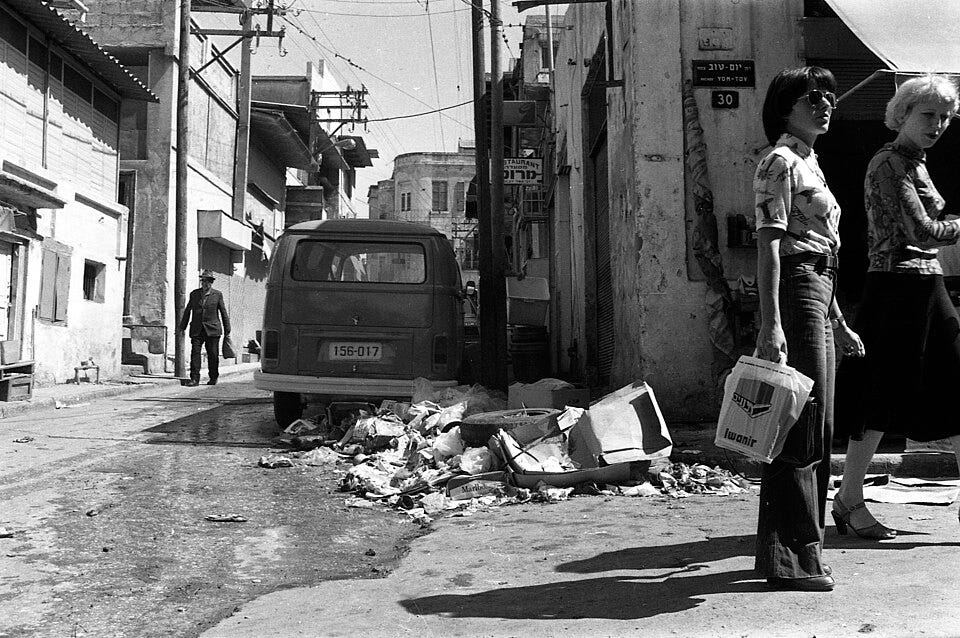

We had beers and talked, watched the sun go down, and walked up Andromeda Hill to see the cityscape at night. Then we strolled down through the narrow, winding streets of old Jaffa and all the markets filled with Yemeni, Egyptian, and Palestinian Arabs, Ethiopian Jews, or the rare Filipino or Chinese worker. When our hunger finally found us, for dinner we had Turkish coffee and kanafeh, which is goat’s cheese covered with fried, sugary noodles. As they say in Hebrew, it was p’tzatzah.

It’s a weird thing to be in a country where death by terrorist attack is such an immediate and normal part of life that the people actually co-opt words for their own murder in order to describe things they really like.

To give you a sense of how immediate death is here, Israel’s Home Front Command requires that building codes mandate a mamad, or security room built to withstand rocket fire and chemical attack, in all modern construction. The government ensures that the closer you are to potential rocket fire, the closer you have to be at all times to a mamad. So, for example, the government requires that everyone in Haifa be at least 90 seconds from a mamad. But if you live in a Gaza border town, it’s 15 seconds.

And yet, in Israeli slang, amazing food is p’tzatzah. The bomb. Or teel, which literally means “missile,” as in Ha-shawarma ha-zot teel! This shawarma is a missile!

Of course, it’s a very Jewish thing to extract humor from the jaws of death. If you are forced to withstand generations of injustice, you either become profoundly bitter and hateful or you learn to develop a rather fierce sense of humor. Indeed, to this day, the best Holocaust jokes I have ever heard, and the only ones I ever find funny, come from my Jewish friends. My favorite one goes like this. A Holocaust survivor dies and goes to heaven. He meets HaShem and they spend the afternoon hanging out. At one point, HaShem tells the survivor a joke. They both laugh. Then, the survivor asks if he can tell HaShem a Holocaust joke. HaShem agrees, but when the survivor tells the joke, HaShem falls silent. After a minute, HaShem says, “You know, I don’t find that very funny.” And the survivor replies, “I guess you had to be there.”

As they say around here, Shalom.

Saturday, October 28

My friend was a commander in the Israeli military, as well as a tour guide after that, so already with all our talks and the enormous amount of information he gives me everywhere we go, I feel like I’ve been here a few weeks. Talking to him, the topics shift from the eye-opening to the entertaining, and from the strange to the dark.

Here are some random observations. Tel Aviv is awash with stray cats. Breshnev Hasidics, those Orthodox Jews who listen to trance music and take loads of LSD and then close off streets in downtown Tel Aviv and dance with passersby until the police tell them to fuck off somewhere else, are in some ways more wise than silly. Israelis manage to be polite only when required, but without being rude. Tel Aviv smells like the Mediterranean Sea, the citrus fruits of the Carmen Market, coffee, and sunscreen.

As a side note, I’m considering renting an apartment in Jerusalem and staying there a while. My friend who works as a krav maga instructor for the IDF has invited me to stay with his mother until I get settled. Apparently, she lives in a quiet neighborhood in West Jerusalem called Rehavia, where many senior government officials live. According to him, it’s the best neighborhood in the city.

Shalom.

October 29

Breaking news reports 11 rockets have been fired from Gaza, landing on a house and a school in Ashdod. One person has been injured. Meanwhile, the Palestinian leader — head of the government, but not prime minister since they don’t have a ministry — Abu Mazen has said that if the UN bid for Palestinian sovereignty fails, then there’s no point in trying to govern and so he’ll dismantle the government, which of course means Hamas will seize control.

Out the other side of his mouth, he’s saying peace with Israel is essential. Watching the footage of the rocket attacks, it was basically some redneck with a pickup truck. I couldn’t believe it when I saw it.

Also in the news is the separation between men and women in Jerusalem. Buses are separated. Some shops prohibit women. When liberal Israelis go there and try to speak about women’s rights and the sexual apartheid, the religious radicals — Hasidic Jews — call them Nazis and throw bags of trash at them.

Tonight, I went with Omer and his roommate Sharon to watch the demonstrations. Sharon described it as Israel’s awakening from a history almost entirely consumed with security issues when it comes to politics, and now for the first time, they’re beginning to wake up to hard economic realities as Israel’s flirtation with capitalism has evidently played out as a profound failure. Now socialism had a chance.

I simply nodded and said nothing.

But political parties in Israel haven’t changed. They all agree on economic and social issues for the most part. All that really divides the right-wing Likud and left-wing Labor Party, for example, are their approaches to national security.

It’s exhilarating to see so many people in the street, peacefully protesting. You had folks sitting atop bus stop shelters, hanging from balconies, flooding the streets, waving banners, chanting, playing music, drinking beers, discussing politics and so on. Israelis are by necessity a politically astute people. None I have met, though I’m aware they exist, hold the kind of grossly oversimplified views you encounter in the U.S. or Europe, where opinions are largely fed by oddly selective media reports.

When you ask an Israeli their opinion on almost any matter relating to politics, you almost never get an answer that would fit prettily into any configuration of any foreign political stream. Israelis speak from experience, with passion, and in nuances. They also argue like most folks play chess. I love it. But enough stereotyping.

Shalom.

Saturday, November 5

Walking through the Carmel Market today, I saw a man selling fruit, smoking marijuana (which is illegal here) and shouting, “Buy my shit motherfuckers!” My friend Oren translated for me. The market was packed, filled with zahatar and other spices, dates, unusually bright carrots, guava, pomegranates, melons, shirts, CDs, jewelry, and different handcrafted goods such as hamsa — a hand-shaped good luck charm meant to represent the five-lobed leaf Adam and Eve used to cover themselves.

I headed down to the central bus station in Tel Aviv to catch a ride up north. I had seen a slice of how the poorer side of Israel lives, and it was beautiful in its way, walking through the Palestinian markets of Jaffa, south of Tel Aviv, the famous Shuk HaPishpeshim, wandering over the sun-bleached cobblestones of Old Jaffa’s narrow lanes, the air thick with cardamom, grilled lamb, and mint tea, the stacks of tarnished brass lamps, old vinyl records in crates, racks of embroidered red-and-indigo Palestinian dresses, cluttered with chipped porcelain teacups, the occasional oddity — an old sewing machine, a rusted bicycle bell, Ottoman‑era coins — and an old man selling little glass cups of Arabic coffee, sweet and syrupy thick, glowing in the lantern‑lit crowd of treasure hunters and busy shoppers angrily haggling or sipping arak and nibbling on plates of mezze.

But the crowd at the bus station was markedly different. This was the brutally ugly face of destitution, especially at the southern side of the station near Neve Sha’anan, which is one of the starkest, harshest corners in the entire city, with people crushed by poverty on full display, men sleeping upright on splintered benches, flies crawling over open sores on their faces, a woman hunched in a doorway, hair matted with grease, rocking a baby wrapped in a towel that stank of urine, old refugees from Sudan or Eritrea, bare feet swollen and cracked, skin flaking off in white patches, sipping from cloudy plastic bottles of water that have sat in the sun too long, piles of trash choking the sidewalks, rotting food scraps, the stench of piss, one man heating a metal plate with a makeshift flame and pressing the plate against his thighs like a clothing iron, until the flesh sizzled and hissed, then peeling off strips of his own skin so the red beneath was exposed and raw, oozing, ready for the next passerby to gasp and cough up money, having no idea he’d done this to himself. Or more accurately, that he’d found himself in such dire straits that he felt the need to do this to himself.

I rode the bus to Haifa and got out in front of the Hanging Gardens, which were built by a Baha’i believer and are a major attraction here, where the Baha’i faith is actually somewhat common. I had thought Bahaʼi was a New Age religion, but it turns out this monotheistic faith was founded about a century before the New Age movements of the 20th century. Its stand-out teachings are that science and religion can co-exist and the idea that all religions are merely chapters in one long story of spiritual evolution, so for example the teaching of Christianity are meant to be followed by the teachings of Islam, as if Islam is in some way an improvement upon the former. Naturally, of course, the final stage in this long march through the faiths is Baha’i itself.

The city of Haifa is so pretty. Old Arabic architecture in faded sandstone, the glittering sea crowded with kites. No joke, kitesurfing is huge in Israel. And there’s a music festival here now, as well as a gay pride festival. The music festival is strange though. Multiple stages all in one area, but utterly silent as people wear wireless headphones linked to the DJ or band’s equipment. That way, the city’s noise ordinances aren’t violated. Also, all the people stand in the middle dancing together but they can switch the stage they’re listening to with the click of a button. That’s all very cool. But it is weird walking through a crowd of dead silent kids who are all hyped on drugs and dancing like mad.

Naturally, Israel shuts down for shabbat. Even the buses and trains stop working. In fact, I caught the last one up here.

Technically, shabbat begins on Friday when the first three stars are visible in the sky. But these days, they just call it at 6:00 PM. Only the local Muslim shops are open now, which of course do not serve beer. So here I am, stone sober, staring at the infinite sea, which is infinitely lovely, and all I can think about is that guy outside the station back in Tel Aviv, ironing his thighs.

Shalom.

Friday, November 11

I spent an afternoon in the German Colony, a very pretty Arab neighborhood founded in 1868 by the German Templar Society, as I completed research and snacked on kebbeh, falafel and Yemeni araq.

Araq is an interesting drink. It pours clear as vodka but turns milky like absinthe when you add water. Made from anis, or sometimes raisins, the invading Mongolians loved it so much they took it back to their homelands with them where there were no grapes to make it from, so they used horse’s milk instead, and called it airag. I had airag in an old Mongolian ger one night with a pair of Naadam wrestlers, and the stuff tastes like carbonated milk — or the Japanese soda Calpis. The drink was later brought to Korea by the Mongols where it became soju, probably one of my favorite spirits in the world. But Koreans made it from rice, and after the Korean War, regulations prohibited the use of rice for anything but food, so they switched to making it from sweet potato and tapioca instead, which produces pretty awful stuff, but if you can get your hands on the rice-made variety, then you’re holding liquid gold.

Ben-Gurion is a bit touristy, but charming. The buildings are all the color of the desert, square and low, with terraced gardens and sidewalk cafes where tourists sip Turkish coffee and tug on bubbling hookah. The road slopes down toward the beach, where I went for a day to finish a paper I’ve been writing and drink a few rounds of Goldstar, Israel’s dark lager.

God, what a shame you can’t find this stuff outside Israel. I always try to have some of the local beer when traveling, which often ends up being a disappointing experience, but Goldstar is a winner. It’s toasty, warm, but refreshing enough that you can happily sip it on the beach under the pounding sun. I passed out in the sand with the waves touching my heels and then took a stroll along the boardwalk, watching some of the old guys play dominos in the shade, their knees spread wide, shirts unbuttoned and big old bellies hanging out. It kinda reminded me of the parks in China, where the old guys play weiqi, or some of the last remaining places in Seoul where you can find fellas crowded around a game of baduk, or the chess champs of Central Park, for that matter.

On the other end of the hill, at the top of Ben-Gurion, are the Hanging Gardens of Baha’i, where the body of the Báb is buried. The gardens rise above the scenery of Haifa like a great emerald curtain. They’re stunning. And the view from the top is amazing. But you have to be a believer to walk up the glorified steps. Otherwise, you go the long way around. Up top, you can see almost all the way to Lebanon. People came here in 2006 to watch Hezbollah rockets rain down on the city, 93 in all, killing 11 people, like a sizzling showers of deadly fireworks.

Behind this, on the slopes of the Carmel mountain range, is the area known as Carmel, where Jews hang out. I spent a night bar hopping in this neighborhood. I also drove up into the mountains one day with my friends Anna and Yigal, with whom I’ve been staying, and had a look at the areas where last year’s fire stormed across the hillsides. The Mount Carmel forest fire killed 44 people in all and forced the evacuation of over 17,000 people. Some said it was an act of terrorism. One 14-year-old boy from the town of Isfiya admitted throwing a nargila coal into some bushes that caught fire. But as far as I know, the real cause was never identified, though once it got going, there were multiple incidents of people trying to help it along, such as a series of brush fires triggered by arson attacks in and around the West Bank.

After driving past miles and miles of charred earth and blackened trunks, some hillsides entirely stripped bare with an almost lunar desolation, black ash smothering the soil, and maybe I imagined it, but I could swear I smelled the musty warmth of smoldering bark. Anna and Yigal showed me the place where a security bus riding up to help evacuate the nearby prison swerved off the road and crashed into the burning valley below. All the guards onboard perished.

We pulled over soon after and sat on the hood of their car talking, looking at the rugged limestone ridge of Mount Carmen, its slopes once blanketed with Mediterranean pine and wildflowers. We drove on, along Allenby Road and past the Cave of Elijah, where the biblical prophet took refuge and prayed before slaying the 450 prophets of Baal. Then we went down to Kishon River where Elijah slayed the prophets. Not far from us, walking distanced in fact, was Tel Megiddo, a plateau as well as the site of an ancient town where the Book of Revelation describes an apocalyptic battle taking place. The Hebrew Har Megiddo, or Mount Megiddo, became Harmagedon in the Koine Greek of the New Testament, and from there we eventually developed the word “Armageddon” to refer to any apocalyptic battle.

So there I was, around the corner from Armageddon, surrounded by scorched earth, staring into a valley where a hundreds of child-sacrificing, self-mutilating false prophets were cut down and their guts washed away the current, and all I could do was smile because right in the center of the valley, under pillow of ash and dirt, I saw a bright green shoot emerging. And once I spotted the first, I began to spot more, in fact they were all over the place, hundreds of tiny green shoots, some already unfurling their first fresh leaves. Not only were these little pines unbeaten by the fire, but they were strengthened by it, for now there was no canopy to compete for sunlight, and now the ground was laid thick with a nutrient-rich bed of ash.

You know, if I were a writer, I might find something symbolic in all this.

Shalom.

November 14

Last night, I watched a movie with Yigal and drank a bottle of wine from the Carmel Winery, where David Ben-Gurion used to work when he was a young man. Today, I’m taking the train back into Tel Aviv to see friends before riding on to Jerusalem.

Interestingly, Jerusalem is pronounced Yeru-sha-liyam. Isn’t that so much prettier? It comes from the the Sumerian word yeru, meaning “city,” and the Canaanite word salem, meaning “peaceful” or “complete.” Some scholars say the name may have been taken from the Canaanite god of dusk, Shalim, who marked the completion of each day. Perhaps Jerusalem will mark the completion of my trip.

Shalom.

December 2

A friend asked why I’m not sending pictures. At some point, I’m sure I will. But not many. In case any one else is wondering, I realized about a decade ago that I rarely consume the pictures I take later on, and I end up deleting many anyway, until I have a crystalized collection. The fewer I take, the more each image means to me.

Once or twice, I lost all my pictures from a particular trip and became aware of the fact that I hardly missed any of them. I mean, I did at first. But a year or two later, it was as if I had lost nothing at all. So I don’t take pictures anymore. Or hardly ever. Around the time I figured this out was around the same time I decided to keep something more permanent from each country I visit. Something that would not only allow me to take a tiny piece of the country with me, but a more meaningful piece, a piece that would actually leave me the better for it. A skill, a language, a friendship.

Ideally, something that would change the nature of who I am, rather than record a single moment of a particular day. I have loads of photos from my China trip, for example, but the Chen school of Tai Chi that I learned in Yangshuo under one of the greatest living masters of the form, and which I continue to practice most mornings, has left an impression on my soul far deeper than any photograph ever could.

Similarly, there is the Zen practice I picked up in the mountains of Japan and have maintained ever since, the Tibetan meditative practices I learned during my time in Dharamshala, or the Northern style of Thai massage I studied in Chiang Mai. But not every memento needs to be a skill that takes months or years to develop. Sometimes it can be something far, far simpler yet incredibly rewarding. In India, I learned to make the perfect cup of chai from a chaiwala, and it’s still one of the best things I ever learned from a country. In Morocco, I played drums in the Sahara with my Berber guides and learned several new drumming patterns. In northern Italy, I learned the four Roman sauces. These are tiny things, but they add up.

I am not sure what I will take home with me from this blessed land. But whatever it is, I’m sure it will make all my future days that much brighter.

Shalom.

December 9

Yesterday, my friend Omer and I hit the beach and for the first time since landing in Israel, or ever, I swam in the Mediterranean. I’d borrowed a book from Omer’s roommate before we left the house, The Zigzag Kid by David Grossman, and read it all on the beach. More for adolescents, I guess, but a delicious read if you’re at all curious about Israeli literature.

For lunch, we went to a spot called Bleecker Cafe to meet a friend of Omer’s. Last night, Omer and I made shakshukah before going out, which is maybe the closest thing Israel has to a national dish, if not hummus or felafel. And this just might be my Israeli memento. For one thing, I got Omer to walk me through his Bubba’s recipe, and it’s not that complicated. The secret to a good shakshuka is fairly straightforward. Here’s my recipe:

1. “Warm the pan” by heating olive oil and adding onion, bell pepper, chili, garlic. Sauté into a soft, golden jam.

2. “Bloom the spices” by adding cumin, paprika, coriander, cinnamon, saffron. Stir until the fragrances open up. Add tomato paste and cook until it caramelizes.

3. “Build the sauce” by adding crushed, peeled tomatoes with sugar, vinegar, salt, and pepper. Let this simmer about 20 minutes until it thickens.

4. “Cradle the eggs” by making shallow wells in the sauce and then cracking eggs into them. Season the yolks with a little salt, cover the pan with a lid, simmer until the whites are set and the yolks are runny.

5. Garnish with Aleppo flakes, olive oil, za’atar, and cilantro. Serve with challah.

It’s basically poached eggs stewed in tomatoes, onions, garlic, and spices. It’s a very simple meal but very hearty, especially with a good challah, the braided loaf of bread people eat on Shabbat.

Later that evening, we headed out for drinks. On our way to the first bar, we walked past a convenience store in which six guys had decided to start slapping plastic bins and countertops and chanting hypnotic, wordless rhythms. The place was packed. Folks were pulling beers from the shelves, dancing in the middle of the shop. Turns out the crowd was a mix of Arabs, Nigerians, and the guys making music were Brazilian capoeiristas. Pretty shocking to see a party like that pouring into the street from out of a tiny corner shop.

Next we went to Merchav Yarkon, a nightclub converted from the old Tel Aviv police station. Great music. Most of the rooms still had bars on them, but were now full of kids dancing or circled about smoking weed. Everything after that is a slurred blur of laughter and dancing.

Shalom.

December 12

Tel Aviv is safe too. You have thuggish sorts who play tough. Arsim they’re called. The word is taken from the Arabic for “pimp,” and it’s ethnically loaded because it often refers to dark-skinned Mizrahi Jews. But the point is, you do run into arsim, the loud and brash rednecks of Israel, but even so, they manage not to erode the neighborhoods where they live. The working-class Mizrahi neighborhoods of Southern Tel Aviv, like Hatikva and Shapira, are packed with arsim yet lovely places to liv e and work, with rich markets and great street food.

So yeah, arsim are pushy, brash, loud, often working-class young men. Gold chains, tight shirts, flashy cars, lots of cologne, and loud Mizrahi pop music. Think British chavs or Russian gopniks. But you walk about at night, down dark alleys, or you bump into fellas in bars, it almost always comes to nothing. You don’t have the ugly rugged maleness that you find in the United States. It should tell you something about American culture that they would take a concept as beautiful as machismo, which represent essentially everything good that a man should try to be, and render it into macho, its antithesis. I wonder if forcing everyone to serve in the military does something to calm the male need to prove oneself. In my experience, boot camp is a reliable remedy for hood behavior.

Another thing military service seems to do is impart all the women of this country with a deeper interest in political affairs. Of course, having your life always on the line thanks to nearby terrorist activity helps, as does the Jewish tradition of a scholarly upbringing, but you can have a detailed political discussion with Israeli women in a way that you cannot have with most Japanese, Spanish, or American women. Speaking of which, I randomly ran into a girl at a coffeeshop this week and we’ve been seeing each other every day since. Her name is Neta. Apparently, she used to have a position of some importance in the Netanyahu administration. We’re meeting again tomorrow.

Shalom.

December 14

I have to say, I have fallen completely in love with this city. I’ve never experienced such a vibrant urban center in all my travels. Not New York, not Bangkok, not even Miami compares. Walking down the street, you catch interactions, some momentary, some lasting the exchange of a few words, other that spark conversation, but almost constantly, feeding off people, interacting with groups, as if you already know everybody you’re walking past, and everyone is out, sitting in groups on the sidewalk or playing music in the gardens, partying in convenience shops, and all the bars and shops and cafes are flooded and pumping with music, I mean really pumping, and in the end maybe it’s the energy that I find to addictive. Israelis call it avirah, which just means “atmosphere,” but also the vibe of a party, and after a while you come to realize, there’s nothing like avirat Tel Aviv.

Berlin comes close, but Berlin is huge and spread thin. Too many different

neighborhoods with too many different folks who don’t really mingle. The underlying German cultural coldness doesn’t function as a very good social glue. The variety is tantalizing, but they don’t really mingle. Here, Tel Aviv is only about 300,000 people in the city proper and they all live in what’s basically one big hood. There are distinctions, and certain groups do stick to their own a bit, but only locals really know or feel this. To the outsider, it’s like one big block party. I have fallen in love with this place, for all its flaws and faded ghosts, all its social issues and secret sins, this great White City, as they call it, will always have a home in my heart. This Berlin by the sea.

Shalom.

Two of your recollections folded together:

"After a minute, HaShem says, 'You know, I don’t find that very funny.' And the survivor replies, 'I guess you had to be there.'"

This brought memories of my interviews with survivors when I directed the fund raising film for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Each interview starte with general facts and histories, then moved into unique regional events. But then, in each case, the interviewee would say, "I've never told anyone this..." And we would proceed to "you had to be there." The gut punch. Sometimes the banal would be most devastating: one interview that recounted the mundane cruelty of neighbors reduced me to sobbing uncontrollably and calling a "time out." (The archived interviews are at the Holocaust Memorial Museum under the "Campaign to Remember" film project.

And you noted...

"...the Tibetan meditative practices I learned during my time in Dharamshala,"

Memories of my private audience with a Tibetan Rinpoche in mountains above Boulder. Nothing remarkable at first glance. He reminded me to breath and sent me off. I paused on the mountain to reflect. A deer, a young buck, came and stood next to me, also reflecting. (You'll understand.) Time opened up and I realized the Rinpoche was repeating a complaint of long duration he had with me. He was not saying "breath" so much as "laugh." Over many lives he had complained I lacked a sense of humor. I was appropriately admonished.

These recalls came together in your concluding remarks. I take the young pine shoots coming up out of "Armageddon" as an analogy for our ability to breath and laugh in the face of worldly horror.

Wonderful. Thanks.