American Nazis: The 1930s

This is the first of a 10-part series on Nazism in the United States. Each part will focus on one decade in American history to help shed light on the evolution of the movement within America.

As Adolf Hitler rose to power in the 1930s and the Nazi Party seized control of Germany, Nazism was also taking root within America. There were camps, rallies, parades, publications and more. While the vast majority of Americans vehemently opposed Nazism, that did not keep the movement from making significant inroads. Here are some of the major highlights from that period.

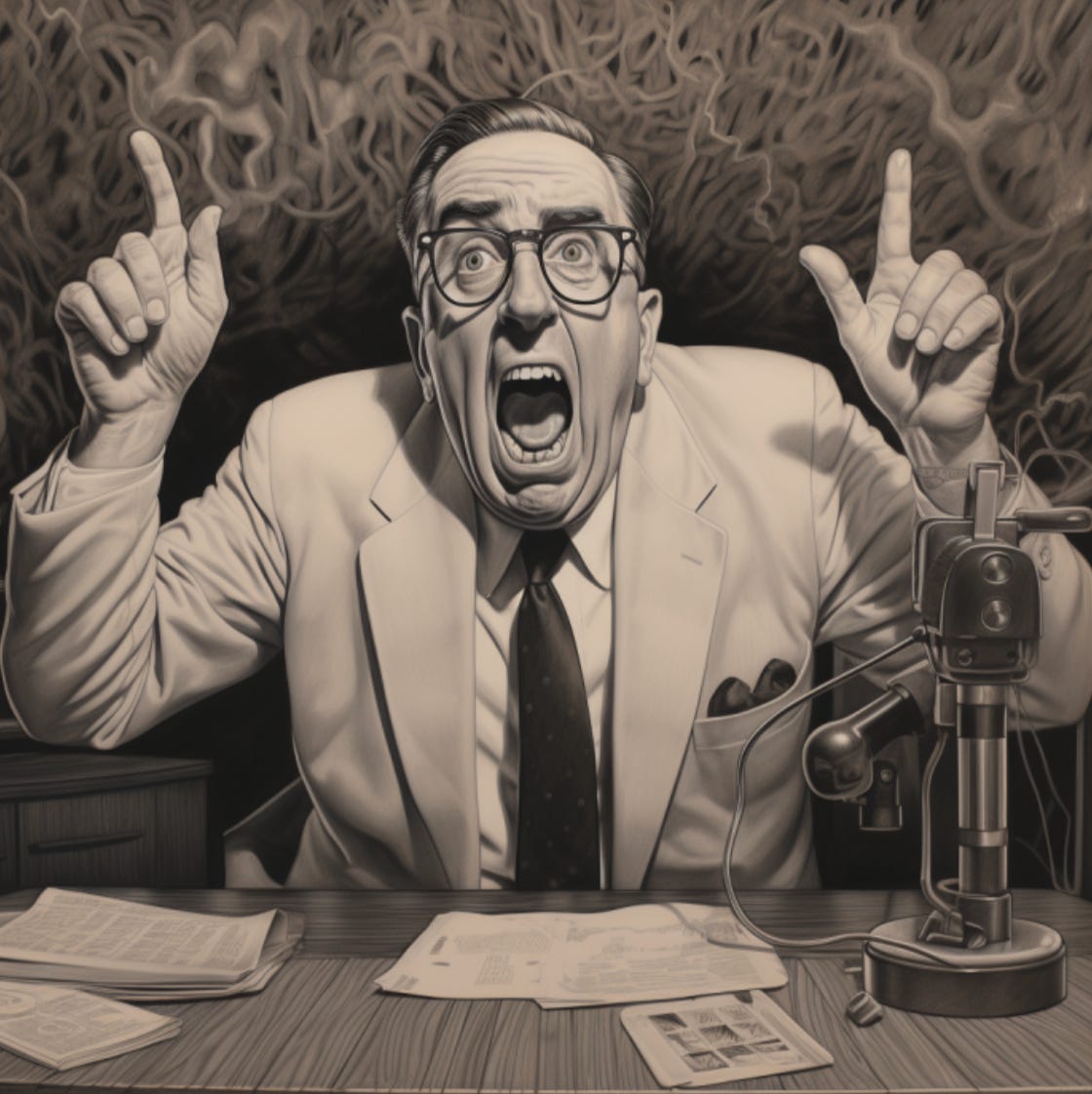

The Radio Priest

The little town of Hamilton sat beside a harbor among the silent cedars and sugar maples on the shores of western Lake Ontario. It was here that young Charles Edward Coughlin came into the world on October 25, 1891, born to Irish and Scottish parents. At the age of 20, he entered St. Michael’s College in Toronto and stepped into the service of the Lord in 1916 as an ordained Roman Catholic priest.

Coughlin served several parishes in the Toronto area before moving to Detroit in 1923, where he began broadcasting sermons from a church called the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan. His first major broadcasts focused on religious subjects, mostly teachings from the Bible, as well as countering the local Ku Klux Klan and their anti-Catholic rhetoric. He was popular, but when the Great Depression hit he shifted from religious to economic and political issues, and that’s when Coughlin really took off. He became a phenomenal success, amassing millions of listeners.

Folks called him the Radio Priest.

As Americans struggled to get back on their feet, Coughlin took to the airwaves to fill their sails with a weekly dose of hope. He was a huge supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, famously saying, “The New Deal is Christ’s deal.” But as the troubles of the 1930s wore on and the public grew impatient for improvement, Coughlin became one of FDR’s most vocal critics.

In time, he also began to direct his anger toward a new target: Jews.

Amazingly, Coughlin’s antisemitic rhetoric intensified even as news of what was happening to Jews in Europe reached America. His early criticisms were of Jewish elites, cast within argument about the harms of capitalism, but soon he took things much further and before long he was paraphrasing passages from Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Eventually, the only difference between his diatribes and those of Adolf Hitler himself was that his were not in German.

Coughlin blamed Jews for Nazi violence and, in one speech in 1938, said, “When we get through with the Jews in America, they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing.”

It is tempting to dismiss this as the ravings of a racist lunatic, but one of the most terrifying things about the story of the Radio Priest is the influence he had on American culture. At his peak, Coughlin had 30 million loyal listeners tuning in to his hateful Sunday sermons, making his the largest radio audience in the world at the time.

The Silver Shirts

Born in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1890, William Dudley Pelley was the son of a Methodist minister. Pelley himself was a gifted writer, and won two O. Henry Awards for his work. He later became a Hollywood screenplay writer, and wrote the scripts for the Lon Chaney films The Light in the Dark and The Shock (links to the full films).

But Pelley is best remembered for creating the Silver Legion of America, also known as the Silver Shirts, after Hitler’s Brownshirts and Mussolini’s Blackshirts. This group believed in the superiority of the white race and saw Jews as their enemy.

They wore silver shirts with blue ties and red letter Ls on their chests, which stood for “Loyalty to the American Republic” or “Liberation from Internationalism,” depending who you asked. This was because their ideology was based on their own sense of American patriotism and what we would today call anti-globalism, because just as now, globalism was associated with Jewish elites.

At their peak, the Silver Shirts had chapters, or “garrisons,” in several states and claimed to have 15,000 members. They were especially active in Asheville, where Pelley lived, Los Angeles, which was a hub for fascist activity at the time and where they established a community known as Murphy Ranch, and Seattle, where for example in 1936, they held a rally at the Civic Auditorium—now the Seattle Opera House—where Pelley spoke as the group tried to recruit new members.

The group also had designs on creating a theocratic “Christian Commonwealth” in America, but before they could do so, Pelley was arrested in 1941 for sedition and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

By the way, if you want to read more on this group, I recommend Knute Berger’s article “Meet the woman who fought Northwest Nazis.”

The Pro-America Rally

In February 1939, a group known as the German American Bund held a rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The event was called the Pro-America Rally.

Over 20,000 people gathered to support and celebrate the group’s fascist ideals. Fritz Julius Kuhn, the founder, had been busy hosting camps and other events across America for years, all in the name of promoting Nazism among German Americans.

The summer camps operated in a number of states including New York, New Jersey and Wisconsin. But they were not really summer camps in the traditional sense. They were, in fact, indoctrination camps where American kids were taught Nazi ideology, sang Nazi songs and performed Nazi military drills. In effect, they were Hitler Youth camps.

That day in Madison Square Garden, Kuhn and his associates erected a 30-foot portrait of George Washington and while thing was made to look like an Americanized Nazi rally. Kuhn gave a lengthy speech in which he attacked Jews in the media and called for a “white, Gentile-ruled United States.”

But outside the event, a massive crowd formed to protest Kuhn and his supporters. In fact, by some estimates, the crowd outside the event was five times larger than the event itself.

The event was also slammed in the media, the Bund declined in support and Kuhn was later arrested for embezzlement and deported to Germany after serving his sentence. But while the Bund itself failed, the rally proved that Nazi sentiment was not limited to Europe—or the Radio Priest’s audience.

Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi League

As Nazi ideologies gained traction within America, Hollywood stars and starlets decided something needed to be done. Then as now, they were eager to use their platforms to provide the American public with moral guidance, and to that end, they formed the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League in 1936.

One member was James Cagney, known for his roles in films such as “Yankee Doodle Dandy” and “White Heat.” Cagney was actively involved in selling war bonds and outspoken about his hatred of Nazism. Another member was Bette Davis, known for classics such as “All About Eve” and “Jezebel.” She too spoke out against Nazism in numerous interviews.

Still other members included Fredric March, Dorothy Parker (who was actually investigated by the FBI for her leftist politics and anti-fascist activities), the comedian Eddie Cantor, the film director Ernst Lubitsch and the screenwriter Budd Schulberg, who wrote the Marlon Brando classic “On the Waterfront.”

In fact, while “On the Waterfront” is not explicitly about Nazism, Schulberg worked to gather evidence against war criminals for the Nuremberg Trials and the movie conveys powerful themes of corruption and oppression that can easily be read as symbolic of how Nazism operates, spreads and turns brother against brother.

But while this Hollywood group did have a positive impact, Hollywood also continued to perpetuate antisemitic stereotypes. For instance, the 1934 film “The House of Rothschild” tells the story of the Rothschild family’s rise to power as European bankers, and while it does cast them in a largely positive light, it also plays on stereotypes of Jews as money-hungry.

On the other hand, there was also the 1932 film “Symphony of Six Million,” about a Jewish doctor and the difficulties of assimilation in American life, or the 1933 film “Counsellor at Law,” about a Jewish lawyer who faces antisemitism.

On the whole, Americans at the time opposed Nazism but you also had examples of overt antisemitism, certain resorts and private clubs refused to admit Jews, universities and medical schools had quotas to limit the number of Jewish students and figures like the Radio Priest were enormously popular.

In addition, antisemitic propaganda in the United States was on the rise and despite U.S. opposition to Nazi atrocities, American public opinion was divided on the question of accepting Jewish refugees. So for instance, when the German ocean liner the St. Louis set sail carrying over 900 Jewish refugees in 1939, the U.S. government refused to admit them and the boat was forced to return to Europe where many of the passengers were later killed by Nazis.

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of Nazism in America during this period was its adaption from its German origins to an American audience. As one New York Times reporter warned in 1938, “When and if fascism comes to America it will not be labelled ‘made in Germany’; it will not be marked with a swastika; it will not even be called fascism; it will be called, of course, ‘Americanism’.”

I remember that Henry Miller wrote about the Nazis in Brooklyn where he grew up, but I can't remember which book. Lots of marching.

I honestly thought the first photo in your post was Keith Olberman, just judging by the emotion.