Always In Time

Reflections on family after seeing an HBO series

What follows is not a review of the HBO series I Know This Much Is True so much as a reflection on my relationship with my aunt, which I have briefly written about before in the essay “Into the Water to Wash the Stones,” and who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia.

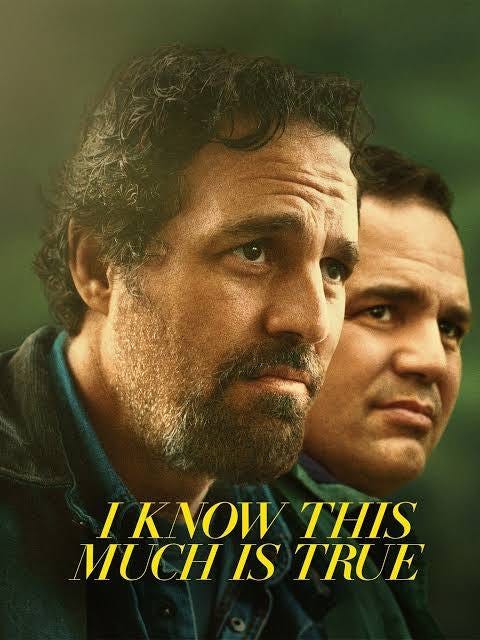

I finally saw the HBO series I Know This Much Is True, based on the book by Wally Lamb, in which Mark Ruffalo delivers such an astounding performance that unless you have loved ones with paranoid schizophrenia, you may not be able to fully appreciate the incredible heart and accuracy he brings to the role of Thomas. I binged the whole series in one sitting last night, then sat in silence for about an hour, thumbing through old memories in my mind of a childhood spent running around my grandparent’s backyard in Paterson, New Jersey — good old Silk City — with my father’s sister Nina (the Russian nickname for Anne), who was the only adult who ever colored pictures with passion or played make-believe and meant it.

Nina and I often sat behind the above-ground pool in the backyard, pretending to be astronauts exploring an alien world, or at the kitchen table with our Crayons and coloring sheets, or in the living room watching an episode of Lost in Space. She told me stories about her imaginary boyfriend Jay 5, and I drew pictures of him traipsing through the Solar System. Her mind was one of the most interesting places I knew, until I grew older and began to see the bigger picture, and that it was not always such a pleasant place for her. But even so, there was such a profound tenderness about her, which I have seldom seen in other people, as echoed in the character of Thomas.

You could never visit Nina without immediately getting a warm hello and two wet kisses, one on each cheek. She was and is the sweetest person I have ever known. But her loving tenderness was the very reason everyone was so dismayed when Nina began talking about wanting to stab me to death. For some reason, she felt that if she did this, it would achieve some greater purpose, although no one ever told me exactly what she believed this was. In the HBO series, Ruffalo’s character chops off his hand in the opening scene in the belief that this sacrifice will save the soul of our nation. Maybe no one knew why Nina said those things but my family was panicked, and Nina was ultimately placed in a home.

One of the last times we played together, it had begun to dawn on me that she was not like other people. That she was strange, weird, somehow mentally defective. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I will never forget my grandmother Alla finding me and Nina behind the pool and scolding me for mocking her daughter’s disability. It was one of the few times in my life when I played the part of the bully, toying with the power of poking someone who cannot defend themselves. I have no idea where I learned such behavior. I cannot imagine how I would feel if someone treated my daughter that way. But the look in my babushka’s eyes devastated me. She was a Siberian woman, which meant she didn’t fuck around ever, and she gave me a look like she was seriously considering knocking out my front teeth. Then, after a long moment passed, she gently took Nina’s hand and led her back into the house.

As they walked away, Nina turned to look at me and I saw something on her face I had never seen before. Her mouth hung open in surprise and her eyes were big, dark, and shiny — because they were wet. She was hurt, hurt and confused. Her little David had deliberately harmed her and she could not understand why. I stayed outside, sitting in the grass and feeling like a piece of shit until it got dark. When I came back in, Alla was cooking dinner. I walked over, mustered my courage, and told her I was sorry. She looked down, barely turning her head from the pan in front of her, and nodded slightly to acknowledge she had heard me speak. I had quietly hoped in the back of my mind that an apology would return things to normal. But no. Alla went back to cooking in silence and I slinked off to the living room where I found Nina watching television. Naturally of course, she acted like nothing had happened, and you might imagine that this would be a relief, but it only made me feel worse.

Later, when the family decided Nina had to go into a home, I was terrified. No one told me about the things she had said, of course, so I was left to wonder whether my teasing was the culprit. Were they sending her away because I’d made fun of her? It didn’t make any sense to think that way, of course, but this was the frantic and broken logic of a little boy about to lose the friend he had recently bullied. How could he not blame himself? It was as clear as seeing one domino fall against another. Post hoc ergo propter hoc. But my grandfather Josef refused to give up on her and would not allow his little girl to be put in a home. With a carefully constructed routine, was able to get her to the point where she was holding down a part-time job and had a real life boyfriend. The man should’ve been the head of a psychology department.

Sadly, after he died, no one was able to recreate his method. Without Josef, not even the fancy doctors could help Nina maintain her lifestyle, and she was soon returned to the home. The last time I saw her, she was sitting quietly on the edge of her bed, staring off at nothing. When I came in, her eyes lit up, she shouted my name, gave me two big kisses, and something in my heart settled. Often in the right kind of light, I recall coloring at the kitchen table in the orange afternoon glow, and can sometimes still feel the Sun on my forearm and hear Nina murmuring to herself. She now lives in a home in Connecticut and I have not seen her in years. I hope to get up there soon, but I know it can never be the same. Just like I know I can never take back that day.

The ultimate message of I Know This Much Is True centers around resilience, forgiveness, and healing. In the end, the character Dominick, whose brother Thomas is the one suffering from schizophrenia, nearly tears his life apart caring for Thomas. In the end, the lesson of forgiveness is one of self-forgiveness, as Dominick learns to grant himself the grace of not blaming himself for things that were never his fault, such as when they send Thomas to a home early in the show. He focuses so intensely on his brother’s humanity that he forgets to accept his own, and with it, the mistakes he has made. I could take a lesson, you may be thinking, and while I can forgive myself for being an asshole at the age of five, that doesn’t remove the sting of knowing the memory may wander into Nina’s heart from time to time and echo there.

But while I cannot purge the ghosts of my conduct, other moments echo too, and though our lives have drifted apart, I know this much is true, that if you rummage through the infinite expanse of existence, somewhere in the pile of it all, still the two of us are out behind that pool, even now, giggling in whispers and holding hands, always in time.

Sometimes the things we regret most are a slice of an unremarkable day. Lilliputian to an onlooker, but Brobdingnagian to ourselves. Tied with spider silk, strong as titanium cable, to an event, a memory, a look of disappointment, shock, or pain. It won't stay buried; it rises to haunt us. I have felt it too.